Egypt after the Coronavirus: Back to Square One

The Arab Reform Initiative on August 26, 2020 published on its official website a research paper entitled: “Egypt after the Coronavirus: Back to Square One”, which was co-written by Ishac Diwan, Professor of Economics at Paris Sciences et Lettres; Nadim Houry, Executive Director – Arab Reform Initiative; and Yezid Sayigh, Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center, Beirut – as follows:

Egypt’s recent security and macro-economic stabilization has been built on weak foundations and Covid-19 has further exposed this fragility. Egypt is now back to a situation broadly similar to that before the 2011 revolution: stable on the surface, but with deep structural problems and simmering social grievances, and little buffers to mitigate them. This paper argues for a major shift in the ways the country is currently governed in favor of greater openness in politics and markets, and for the international community to seriously engage Egypt on the need to reform economically and politically.

Introduction:

Egypt’s Sisi has managed a successful security and macro-economic stabilization, but it has been built on weak foundations. Economically, he has relied on the military and the public sector to become the engines of growth and has been unable, or unwilling, to elicit a private sector supply response. His reforms have also come at a great social cost with poverty and precarious employment increasing.

The external shock due to Covid-19 has now hit all the sources of foreign exchange (FX) in Egypt: tourism, remittances, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), gas export, and international capital flows. On economic and social grounds, Egypt’s stability now appears brittle – resilient on the surface but fragile underneath. Can the current governance and economic model evolve to sustain stability in Egypt following the current Covid-19 crisis?

We argue below that while Egypt’s financial prospects had improved after its successful 2016 stabilization, led by the IMF, it was insufficient to deal with the long term fundamental problems confronting the economy, and like previous stabilization efforts, have only provided Egypt with a window of a few years to implement deeper reforms. Post-Covid-19, this window has become much tighter. The economy is now at a serious risk of unravelling in the medium term if the key fundamentals – the economy, social conditions, and politics – do not improve. Accumulating foreign debt to push the problems away will only compound existing imbalances to the point of becoming insurmountable in the future.

Egypt is now back to square one, in a situation broadly similar to that before the 2011 revolution: stable on the surface, but with deep structural problems and simmering social grievances, and buffers available to mitigate them depleting. We discuss in this note the three main sources of vulnerability that expose Egypt to a possible blowout. These are: a macro stabilization with no private sector supply response, the militarization of its economy and the weakening of its civilian component, and the absence of a pressure valve and political space to absorb the deteriorating social conditions and rise of discontent. In order to make Egypt’s growth path more resilient in the future, and in a post-Covid-19 world, some of these tensions will need to start being released. To do so will require an inflexion in the ways the country is currently governed that favour greater openness in markets as well as politics, and encouragement by the international community to finally start addressing its long-term challenges head-on. Misusing this crisis, as has repeatedly happened before, can this time around usher the beginning of the unravelling of the country.

The Covid-19 external and internal shocks

It is the external shock associated with the global pandemic crisis that has hit Egypt hardest, exacerbating the country’s main source of weakness –its international earnings. While Egypt has enough foreign reserves to be able to cope in the short term, the shock is a reminder that, unless current economic trends improve, its future remains vulnerable and uncertain.

Egypt’s dependence on fragile external revenues has never been higher. In 2019, the country needed to raise nearly $100bn to pay for its foreign exchange (FX) needs – to import the goods it consumes and the external services it depends on ($70bn), and to service its external debt. Yet, after decades of pro-market reforms, and a recent mega-devaluation in 2016 of 50%, it managed to export only $30bn of goods (including about $10bn of gas as Egypt became a net exporter of oil and gas in late 2018). The gap was covered by the big five sources of foreign exchange that had improved markedly since the reforms initiated in 2016: remittances (nearly $30bn); tourism (about $15bn); FDI and portfolio investment ($12bn); Suez revenues ($6bn); and official international assistance of about $10 bn (incl. until 2019 from the IMF).

Together, these sources of foreign earnings can be expected to fall by at least 30% in 2020 (IMF WEO, 2020). The largest of these sources – remittances and tourism – are being badly hit by the global pandemic. Tourism has for now collapsed and will likely remain deeply depressed for at least two years, if not more. Remittances seem to have held up so far, but they are expected to fall over time. Approximately 5.5 million Egyptian migrants are concentrated in GCC and other Arab countries, from where 85% of remittances originate. In these countries, millions of workers have been furloughed or fired, or are only paid partial salaries. Beyond the short term, low oil prices are accelerating the policies of nationalizing labour in the GCC, leading over time to a permanent fall in the demand of Egyptian work abroad, and of remittances. Suez earnings also fell and are expected to remain low with lower international trade traffic. FDI has been going mainly to the oil and gas sector (74% in 2018/2019), where prospects have fallen considerably together with oil prices. Moreover, related to the Covid-19 global crisis, flows to emerging markets have taken a big hit globally, and the flight of hot money out of Egypt is reported to have been above $10bn in recent months. As a result, international reserves, at an all-time high of $40bn before the crisis, have fallen by $5bn in the first quarter of 2020 alone.1

Egypt had no choice but to borrow again in order to plug the growing FX hole. It received an IMF $2.8bn emergency loan in May 2020,2 and a month later, an additional $5.2bn Stand-by Arrangement.3 In May 2020, Egypt also raised $5bn in its largest-ever issuance in international bond market. Its comeback was seen by analysts as relatively successful, but it still faced stiffer terms than in the recent past.4

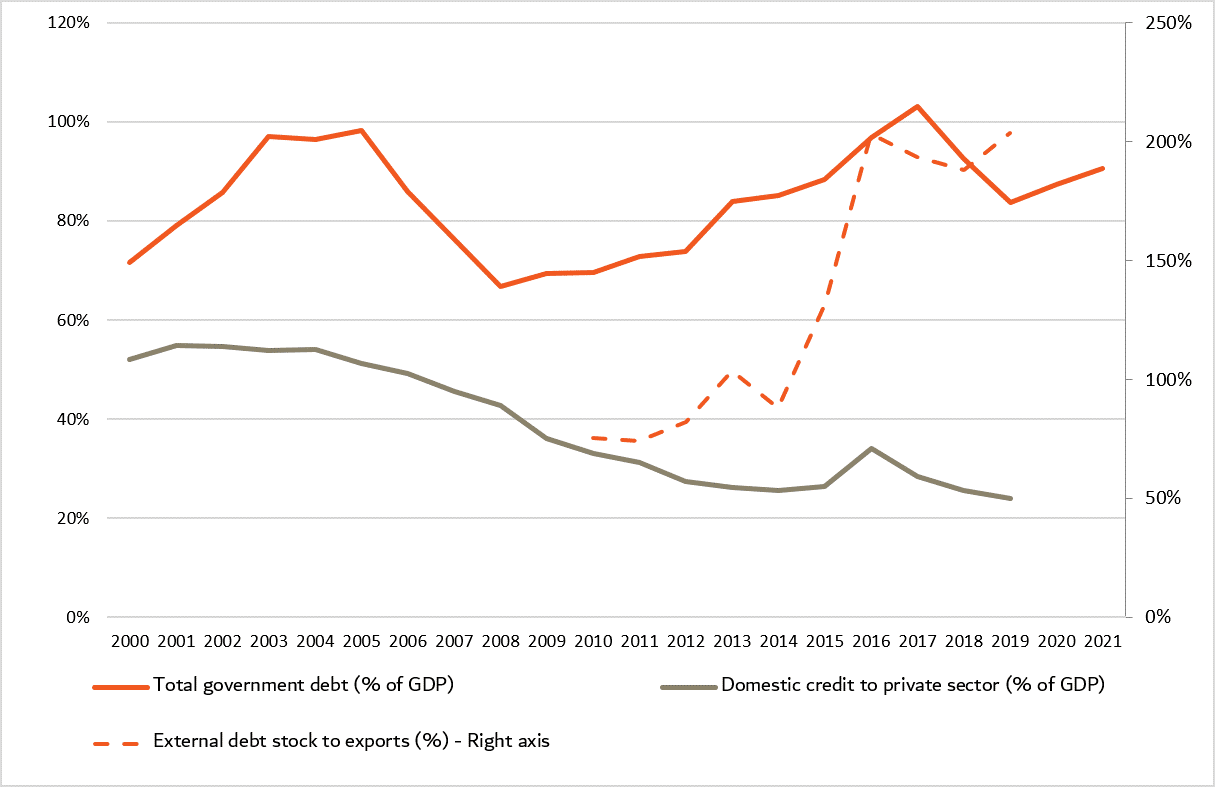

These new borrowings add up to an already fast-growing public debt, which starts raising red flags relating to its sustainability. Since 2012, public debt has grown faster than the economy, and it now stands at over 90% of GDP. It is mainly internal, but the external portion has grown fast, and now surpasses 200% of exports of goods and services. At over $120bn, external debt requires not just servicing ($13bn in 2020), but a large part needs to be refinanced in the coming two years (including the 25% of foreign debt due to the GCC countries). Thus, its external debt already exposes Egypt to an important source of vulnerability – it will become much more onerous should interest rates rise, or the Egyptian Pound devalues further. Egypt is now classified by various analysts among the five riskiest EM countries (the others being Bahrain, Pakistan, Lebanon, and Mongolia).5

Figure 1: Debt and credit

Sources: IMF & World Bank & Central bank of Egypt for the last year (fiscal 2018/19) for external debt/export.

Note: The “external debt stock” is the sum of public, publicly guaranteed, and private nonguaranteed long-term debt, use of IMF credit, and short-term debt.

Besides increased borrowings, Egypt will have to consider a further devaluation of its currency to reduce its imports, and an increase in domestic interest rates to contain capital flight. These measures will deal a further blow to the standard of living of its poor and middle class. The only long-term solution, which has been recognized since the 1990s but never attained so far, is to encourage the country’s private sector to produce more tradable goods: for its local market (to reduce imports), or for export markets.

The external and internal shocks have also weakened economic growth. The IMF now predicts growth to fall from 5.5% to 2% in 2020, just below population growth (IMF WEO, 2020). Unemployment, which was slowly declining, is expected to rise again to at least 12%. A relatively small part of the slowdown is related to the internal effects of Covid-19, but there are risks that this may grow in the future. So far, social distancing measures have remained modest – mainly night curfews, and the closing of public spaces. While initially, Egypt appeared to be spared by the virus, infections have surged since June with the WHO confirming 74,035 cases of infection with 3,280 deaths.6 Many in civil society distrust these figures given the authorities’ attempt to silence doctors and critics of the government’s response.7 If numbers continue to rise, the effect on domestic demand and production would be increased.

The bottom line is that Egypt cannot continue, after the Covid-19 crisis, to ignore the reforms needed to boost its exports, as it will not continue to enjoy the luxury to borrow its way out of difficulties for long. Increasingly, reliance on reactive short-term solutions will become more expensive and less available.

Economic stabilization without reforms

By some accounts, Egypt’s macroeconomic stabilization, in the context of a $12n IMF Extended Fund Facility programme during 2016-19, was a success. In any case, it was necessary. The programme followed the 2013-15 period where Egypt was largely stabilized through support from the GCC ($23bn between 2012-15). This support however largely ended up subsidizing consumption by plugging the FX hole but did not push the government to take measures to reduce the internal and external imbalances. In contrast, the IMF required, as a pre-board condition, that the Egyptian Pound be devalued by 50%, which while extremely painful socially did manage to reduce the external deficit. The real success of stabilization, however, should be judged by its ability to reduce the chronic internal and external imbalances in a sustainable way. The important question is whether this was achieved.

In trying to respond to this question, it is useful to compare the 2016 IMF programme with the previous IMF involvement in Egypt, in 1991. In both cases, the IMF programme required the government to increase energy prices, reduce subsidies, unify the exchange rate, increase interest rates, reduce the growth of credit, reform the tax system, and reduce the budget deficit. While the circumstances in 1991 and 2016 are different, the comparison shows that in both cases, having a “successful” stabilization programme is not sufficient for medium-term progress if the structural constraints in the economic and political realms are not addressed.

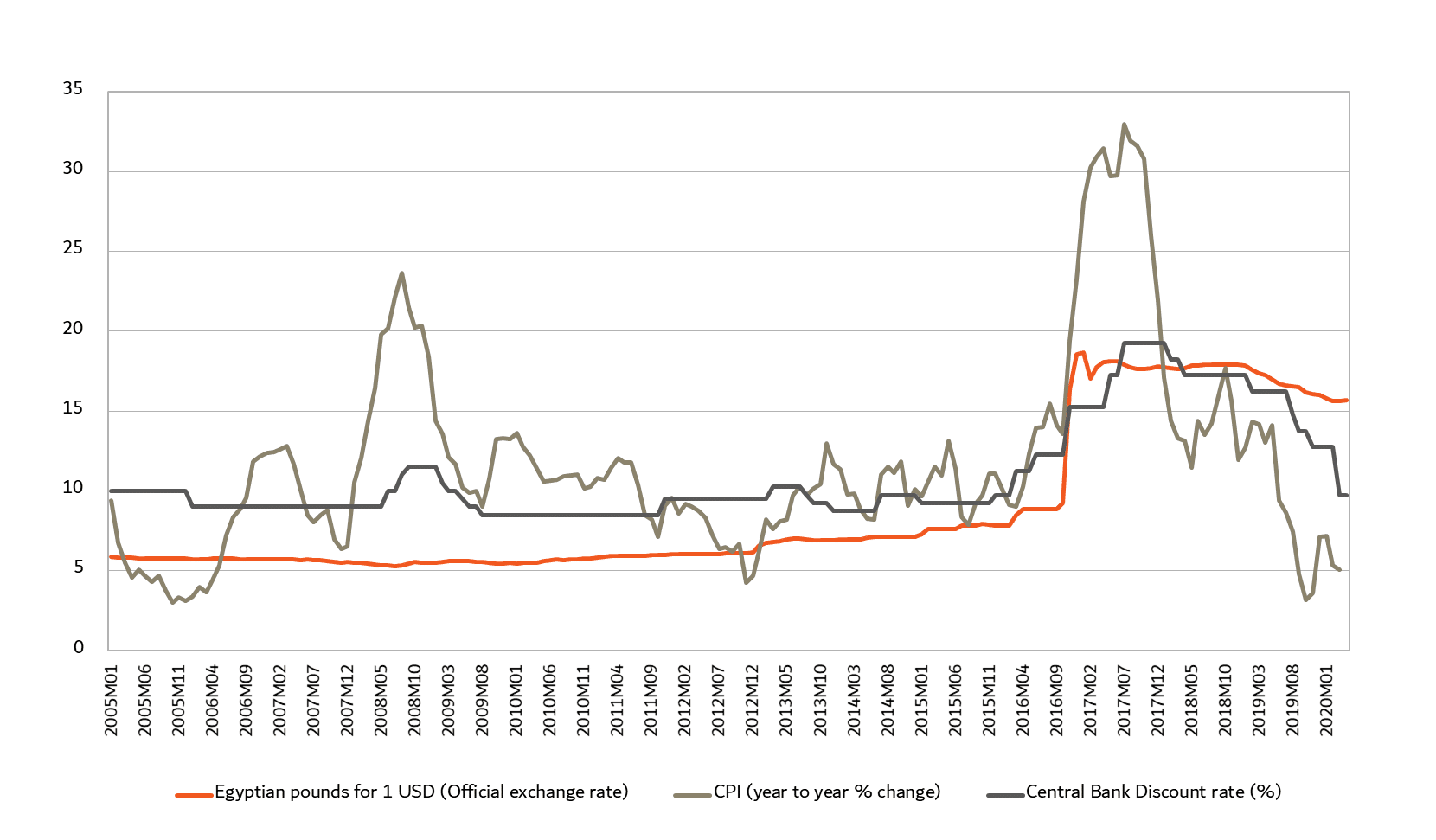

In both cases, Egypt successfully stabilized its economy by essentially tightening its belt sufficiently to attract international assistance, remittances, and FDI. Following a sharp rise in interest rates (between 5- 10% in real terms), FX came gushing in, allowing reserves to rise from $17bn to $45bn and the Egyptian Pound (EP) to stabilize rapidly. In fact, so much capital came in that the EP was allowed later on to appreciate again (therefore providing an even greater real return to capital). While the devaluation created inflation, which went up to over 30% in 2016-17, it was rapidly contained by forcing real wages to fall steeply (see further below).

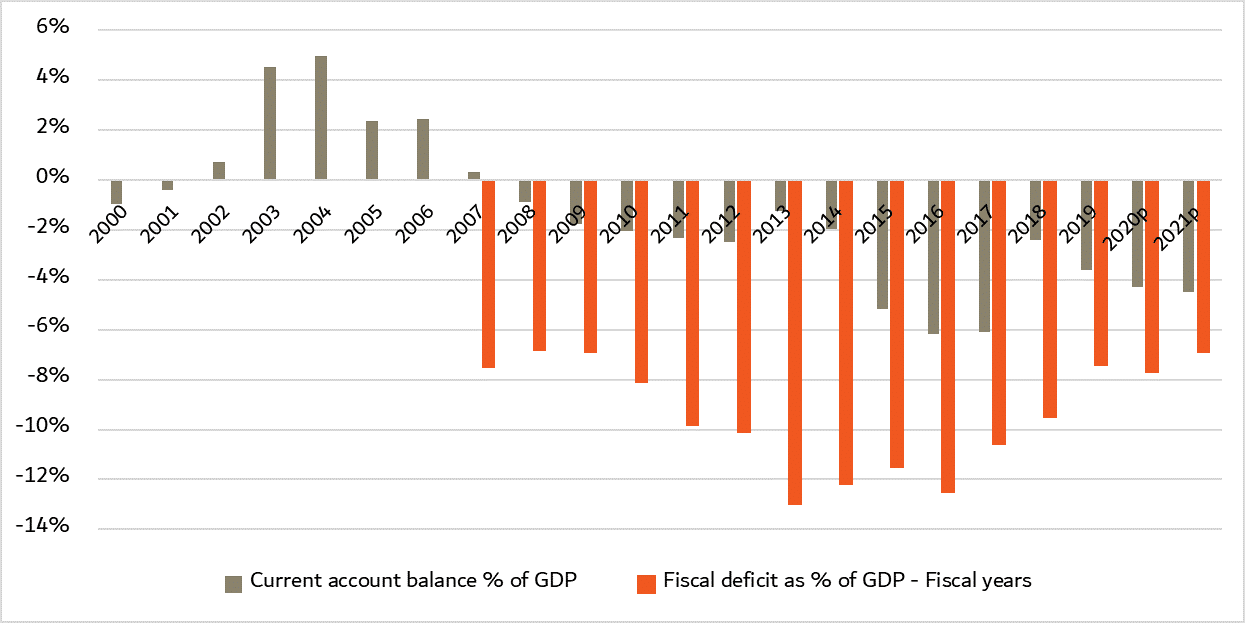

Figure 2: Current account and fiscal deficit

Sources: World Bank World Development Indicators and IMF for the last two years

At the same time, Egypt experienced a significant reduction in external imbalances after 2016, with the current account deficit declining from 6% of GDP in 2015 to 2.6% in 2019. This was driven primarily by cutting imports, and with the strong recovery in tourism. There was also a shift to net exports of oil and gas as domestic gas production took off in 2018. However, traditional exports remained flat, in spite of the heavily devalued exchange rate.

Figure 3: Exchange rate, inflation and interest rate

Source: IMF for CPI and Central Bank of Egypt for discount rate and exchange rate.

Note: “CPI” is the consumer price index, the standard measure of inflation.

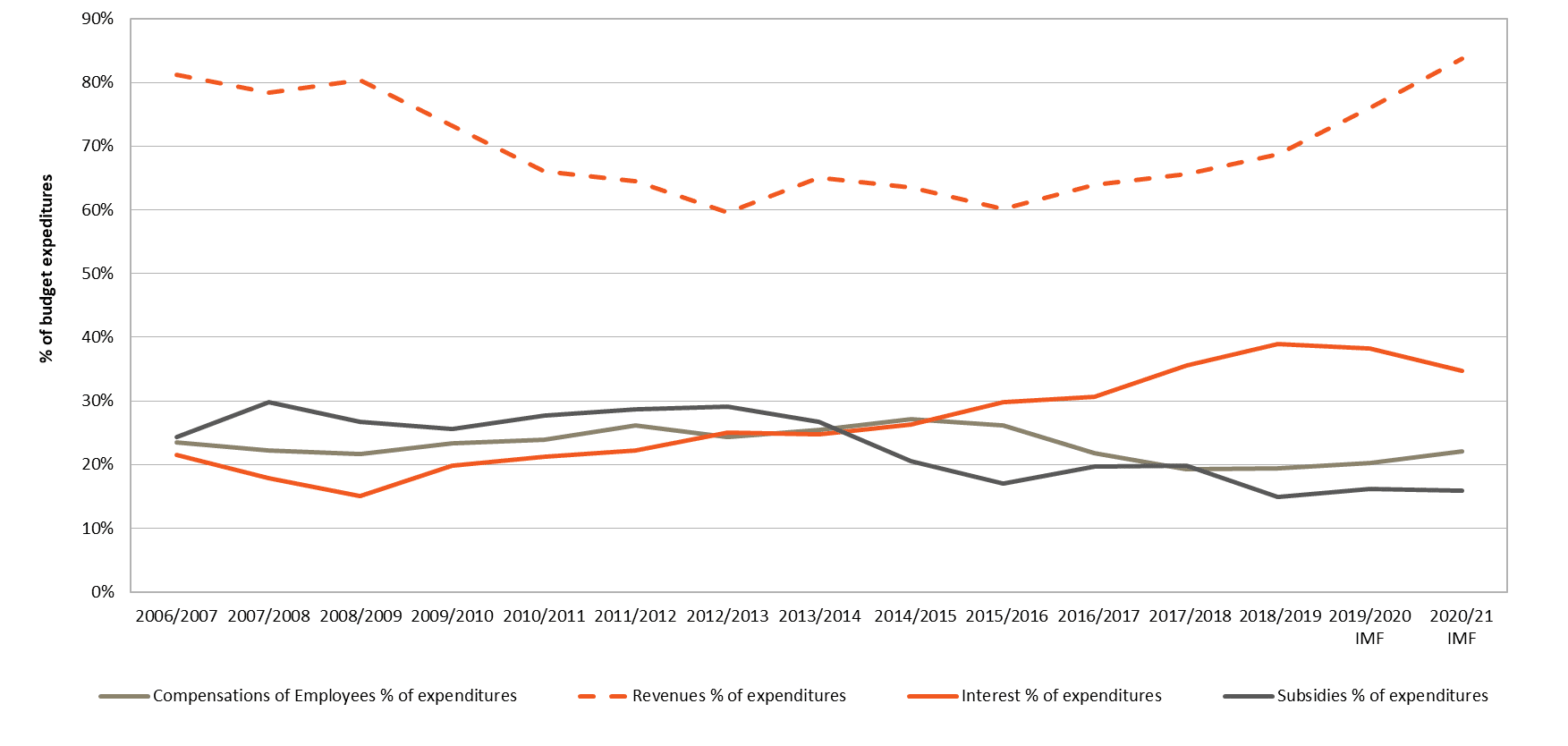

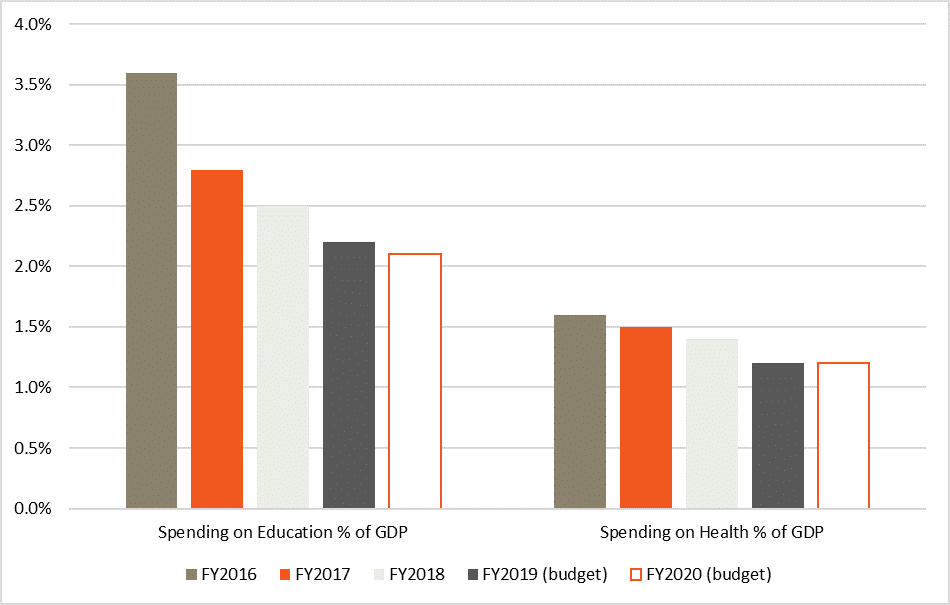

Between 2015 and 2019, the budget deficit also fell, from 12.5% GDP to 6.7% (with the primary deficit swinging from -3.3% to a surplus of +2.2% GDP). Budget cuts of this magnitude (nearly 6% GDP) are not easy to implement, as they create political dilemmas that must be managed. Between 2013-15, Sisi, first as de facto ruler and later as president, resisted budget cuts (and devaluation) in order to stabilize his rule, but this ultimately made the 2016 adjustment larger and more abrupt. The 2016 programme ended up cutting deeply into subsidies – they fell over the last four years from 4.1% to 1.2% of GDP. At the same time, the public sector wage bill was squeezed from 8% to 5% GDP. Public expenditures on health and education also fell, and stood at a meagre 4.5% GDP in the 2019 budget. These were meant to be squeezed further to 3.3% GDP in the 2020 budget. Subsidies and social protection, which stood at over 7% GDP before the IMF programme are down to about 4% GDP, with less than 1% GDP now targeted at the poor. On the other hand, tax revenues remained stagnant, despite the introduction of a VAT, rising marginally from 13 to 14% GDP.8

Figure 4: Composition of budget expenditures

Source: Central Bank of Egypt and IMF for the two last years’ previsions

By 2019, Egypt had a growth rate of 5.4% (vs 4.3% in 2015). But as we will see below, this growth was neither sufficient to improve social conditions nor inclusive. An important reason is that the policy mix had to rely on maintaining a high-interest rate environment to attract remittances and financial flows. As a result, while social services and wages were deeply cut, interest payments on servicing public debt rose to consume nearly 10% GDP, about a third of government expenditures, and two-thirds of tax revenues.

Covid-19 has complicated matters more. Pre-Covid-19 crisis, core inflation was down to around 8%, and the budget was on track to achieve a deficit of 5.4% GDP in 2020 (and a primary surplus of 2% GDP), in line with the IMF targets. The Covid-19 crisis has changed this: a projected decline in revenue and an increase in expenditure are now expected to increase the fiscal deficit. To offset the impact of Covid-19, Egypt has provided tax breaks and cheaper energy to affected firms, and enlarged its safety net, for a total fiscal cost estimated at 2.2% of GDP. The government has pushed interest rates down to contain the deficit, but this is unlikely to be sustainable, as it risks generating even larger capital flight (and/or lower remittances).

Thus, as in 1991, the essential worries concern the vulnerability of external earnings, the fast growth of public debt, the sustainability of growth given the timidity of the private sector, and the negative incidence of the policy mix on poverty and distribution. As before, the main question is why it is that the private sector did not grow further, creating sustainable exports and good jobs, given the macroeconomic stability brought about by the stabilization effort.

Meanwhile no supply response from the private sector

In spite of the deep devaluation, which makes imports more expensive and exports more profitable, the private sector supply response did not materialize. Imports shrunk, but exports did not rise – Egypt’s non-oil exports, which have been weakening since 2011, now stand at only 6% of GDP. This is an old story in Egypt, as previous reform attempts since 1991 were also able to stabilize the economy but failed to generate much dynamism in the private sector.

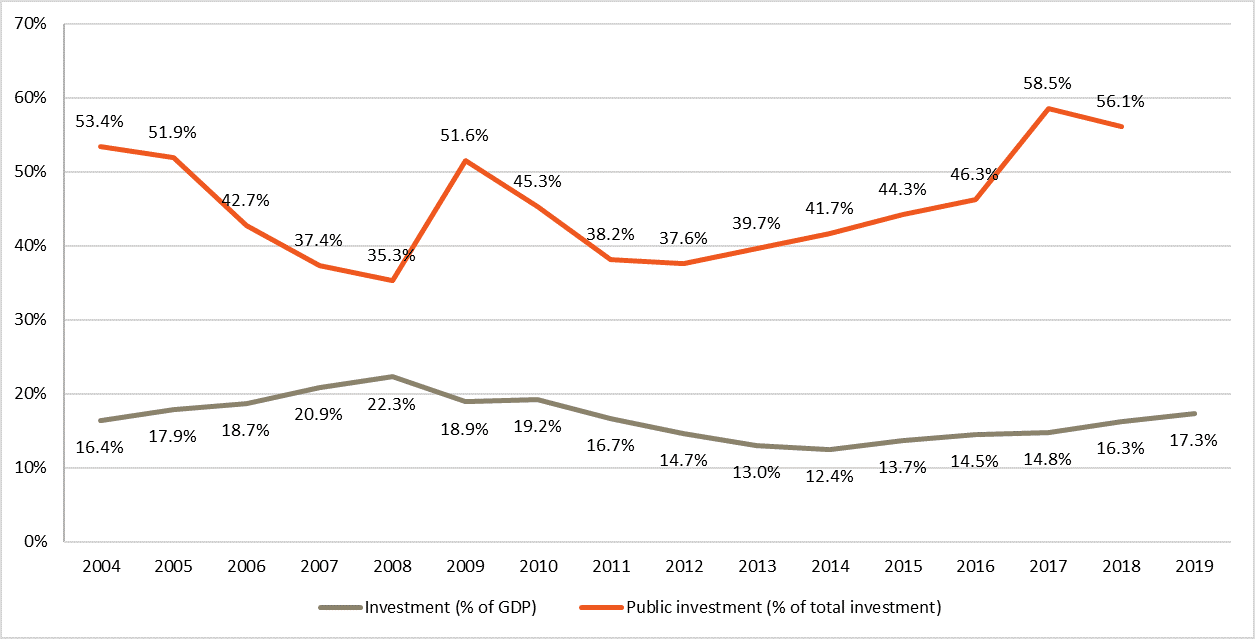

Figure 5: Total investment and public investment

Source: World Bank

Note: Investment, according to National Account definition, is the non-financial investment and the stocks variations are deduced.

But beyond this apparent parallelism, it is important to realize that the current performance of the private sector is at an all-time low. According to World Bank data, the total investment is now at about 15% of GDP (vs MENA developing countries average of 23%, itself one of the lowest in the world). The level of private investment is now at 6% of GDP – even lower than during Nasser’s socialist period. In comparison, the 1991 reform period was able to raise private investment from 10% of GDP in the early 1970s to 19% in the early 1990s. Investment by the central government is also down to about 2.5% of GDP. The rest – about 6.5% of GDP – is made by State-Owned Enterprises and the military sector.

The causes of the low level of private investment continue to be hotly debated. 9 Several possible causes have been noted. A first hypothesis relates to the crowding out of finance by the public sector that reduces access of private firms to capital. Pre-2011, credit to the private sector was around 20% GDP, already one of the lowest such ratio in the Middle East (for example, around 100% GDP in Tunisia, Jordan, and Lebanon). By 2015, it had fallen to 14% GDP, and in subsequent years, it fell as low as 7.5% GDP, before starting to recover. The goal has been to raise it gradually back to 20% by 2020. On the surface, low access can be explained by the redirection of credit towards financing the government deficit. But this explanation is not totally convincing, as financial crowding out was always a factor in Egypt.

Other reasons have to be sought. Three possibilities are cited in the literature. First, private firms may be reluctant to invest in expanding capacity as long as political risk is perceived to remain high. This must have been especially the case for the large firms closely connected to the Mubarak regime, due to their loss of political protection. Second, with poor capacity to be internationally competitive, firms have had to shrink in the face of the higher cost of imported inputs (due to devaluation) and the lower internal demand (generated by the impoverishment of the population). Third, the private sector is facing fierce competition by the military economy, which has been promoted by the new regime since 2013.

The IMF programme of 2016 (like that of 1991), was predicated on a gradual move from stabilization to structural reforms that would favour private sector growth. Yet, the requirements were minimal, notably “streamlined industrial licensing for all businesses, greater access to finance to SMEs, and new insolvency and bankruptcy procedures”. Still, many of these conditions were not satisfied, or poorly so. The 2019 Article IV IMF report on Egypt notes that private sector growth remains constrained by “ the legacy of inward-oriented economic policies and a prominent role of the state that has constrained efficient resource allocation and weakened the ability of Egyptian firms to compete in external markets. Improved external competitiveness will require a focus on deepening structural reforms to re-orient Egypt toward private sector and export-led growth.” The report adds that: “A private sector that can generate the required sustained growth and jobs depends on reducing corruption and shoring up legal systems – where Egypt has more work to do”.

There was some limited progress in the past few years, on paper at least, including simplified industrial licensing, and the enactment of bankruptcy and public-private partnership laws. The government has also begun to sell off state-owned companies to large international investors and Arab Gulf financial institutions, in addition to small public offerings on the Egyptian stock exchange. It is unlikely that the new IMF programmes will succeed in pushing for faster progress. The new IMF programme was produced in haste, amidst a global surge in demand for IMF support, and an urgent need to rapidly support Egypt’s faltering external balances. As a result, it only includes broad wishes for progress, with the press statement saying that: “the authorities have pledged to continue structural reforms… the budget process will be improved, more light will be shed on the financial operations of state-owned enterprises and economic authorities, competition will be strengthened by helping level the playing field, and the customs law will be amended to improve Egypt’s investment climate.” Once again, short-term considerations seem to justify weak conditionality, which is unlikely to change the political calculus sufficiently to yield the type of change that can start to secure Egypt’s future.

The political constraint to private sector development

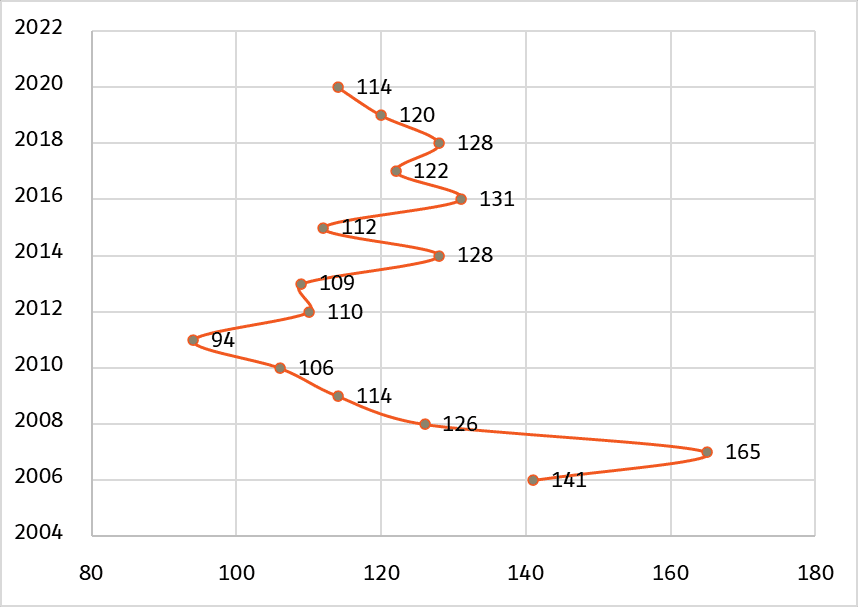

Deeper down, why has Egypt not been able to reach its potential for economic growth and job creation? In the decade before the 2011 uprisings, relatively high GDP growth was concentrated in narrow parts of the economy and failed to trickle down to wide segments of the population. In retrospect, little attention was paid in Mubarak’s Egypt to the development of the institutions and rules needed to energize a market economy – a trend that persists under the rule of President Sisi. Instead, the investment climate has been poor, with the country ranking in the World Bank’s “Doing Business” fluctuating between 94 and 165 (over about 190 countries world-wide) – with the most recent rank of 114 in 2020. The main weaknesses are found to be in “enforcing contracts”, and “resolving insolvency”, pointing to the poor performance of the justice system and the banking sector. Other indicators point to a high level of corruption – Egypt scores 35/100 on the Transparency International Index (well below the global average of 43).10

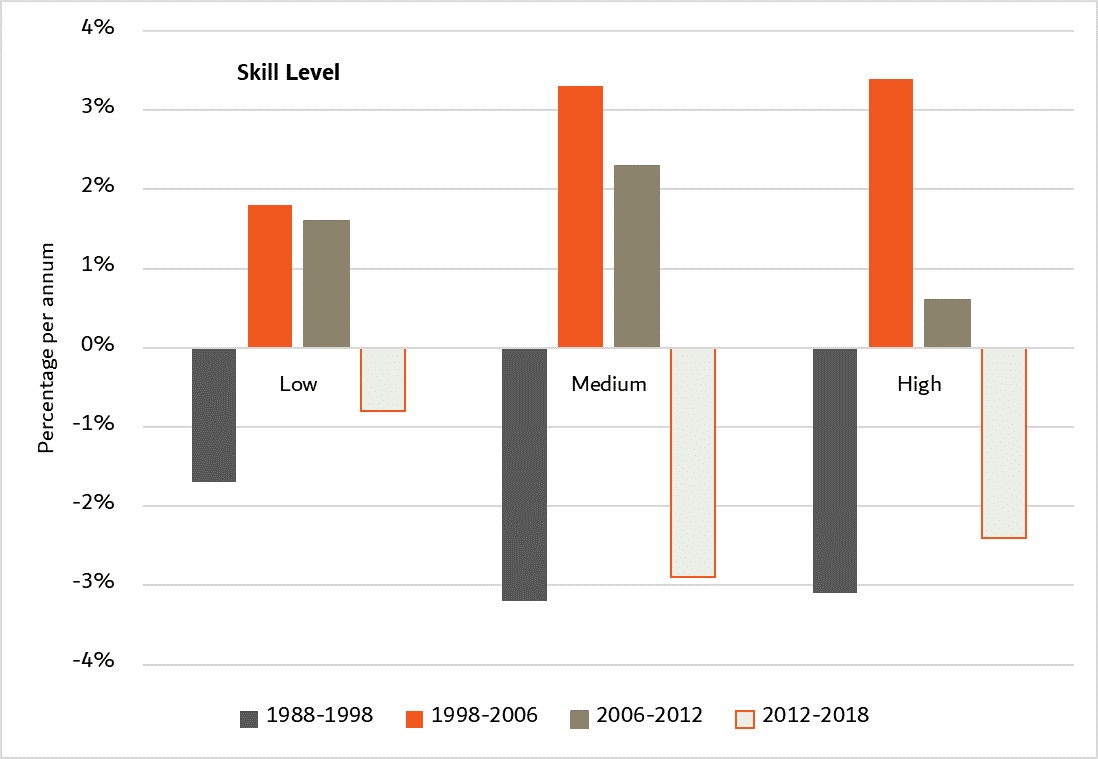

Figure 6: Median real wage growth per period and by skill level

Source: ELMPS 1988 – 2018 as calculated by M. Said, R. Galal & M. Sami, “Inequality and Income Mobility in Egypt”, Economic Research Forum, Working Paper 1368, Nov. 2019.

Instead of simplifying the heavy regulations that impede firms’ development, and applying simpler rules in a fair manner to all market participants, attempts to attract investment have historically taken the form of creating exceptions to the rule – through free zones, investment guarantees, and parallel regulations. Thus, for example, laws such as anti-trust, consumer protection, and regulation of utilities were not introduced until the mid-2000s, over 15 years after the initiation of reforms in 1991. When these reforms were initiated, they had severe limitations in scope, were not implemented by autonomous agencies, and had plenty of exceptions, which reduced their effectiveness. These procedures have been used to provide special privileges to firms with political connections. But they have weakened the ability of middle size firms to expand, encouraging instead the growth of a sprawling informal sector.

The dominance of a few politically connected firms in the economy is not new in Egypt. The phenomenon was always driven by the contradiction between the need to liberalize the economy, and the desire to preserve power. Sadat’s first Opening (“Infitah”) involved a handful of crony allies. Mubarak relied in the 1990s on a slightly larger class of connected capitalists. In the early 2000s, when the country’s policies shifted towards accelerated privatization and financial sector and trade liberalization, the circle of friendly cronies expanded more. These firms participated in the modernization of the economy, spearheading the development of new sectors and the expansion of old ones, backed by state favours and international and Arab finance. The government erected barriers to entry even as it engaged in economic reforms.

There are several ways in which the presence of large privileged firms weakened the economy.11 First, their high level of capital intensity, and low levels of efficiency, allied with a highly privileged access to capital, resulted in low levels of allocative efficiency in the economy.12 Second, these privileged firms compete unfairly with more efficient medium size firms, reducing their market share, and resulting in much lower incentives of all economic actors to invest in innovation. This results in low levels of dynamic efficiency in the economy. Third, the great influence of the connected businessmen (none were women) on policy setting results in an institutional frame that continues to discriminate against the needs of small firms, pushing most firms into informality – reducing informality would have required the simplification of rules and a fairer enforcement.

Together, these factors have led to a corporate structure characterized by a double “dualism”.13 First, there is a deep division between formal and informal firms, with a large base of low productivity small firms that have an extremely low level of access to public services and to the formal markets for inputs. There is also a second rift within the formal sector between large politically privileged firms and middle-sized unconnected firms. In this three-way split of the corporate sector, middle size firms, which tend to be the most dynamic in the rest of the world, are squeezed between the very large and very small firms. They are unable to get market shares away from the very large firms, even though they tend to be more efficient, because of the unfair privileges that their competitors enjoy. At the same time, they suffer from “unfair competition” from small low productivity firms that escape from the regulatory frame altogether.

As noted earlier, some modest reforms have been initiated in recent years, most recently, in the bankruptcy code. But Egypt has trumpeted reform before, with disappointing delivery. A continued focus on mega-projects, such as a new administrative city between Cairo and the Suez Canal, suggests that this time may not end differently. Indeed, Egypt has been reluctant, before the Covid-19 crisis, to ask for the renewal of the IMF programme, knowing that a second programme will largely focus on the opening up of its economy to the private sector. But contrary to the past, the Sisi regime does not count on the large crony capitalists of the past to generate growth. Instead, it is has counted, so far, on the momentous growth of the military economy.

The “militarization” of the economy

The army has been historically subjected to the severe budgetary pressure by the state. Its formal budget accounted for 20% expenditures at the beginning of Mubarak’s presidency and 6% (of a much smaller budget as a share of GDP) at its end.14 As a result, the army had to expand its economic activity to survive.15 But the reasons for the dramatic increase in both scale and scope of military involvement in the economy since Sisi came to power go beyond survival and even opportunistic motives.

This expansion is one of the more remarkable features of the Sisi era. Since he assumed the presidency, the Engineering Authority of the Armed Forces has taken a high-profile lead in managing major public infrastructure and housing projects, including an expansion of the Suez Canal and construction of an entirely new administrative capital in desert lands to the east of Cairo. Various military agencies manufacture a wide and diverse range of civilian consumer goods, deliver contracting, management, health care, and other services, import basic food commodities and medical supplies, extract and process natural resources, reclaim land for cultivation and agri-business (much of which they also undertake), and have expanded into tradeable commodity sectors they had mostly avoided previously. Military factories that used to manufacture missiles, aircraft, or rockets are now heavily utilizing their facilities and labour to produce consumer goods such as washing machines, auto parts, fridges and other appliances (Abul-Magd, 2015). In doing so, the military both employs private companies as subcontractors and, increasingly, competes head-to-head with them. In all, it managed approximately one-quarter of all publicly funded housing and infrastructure projects in 2014-2018, and a year later claimed to employ five million people.16

The military’s net value added cannot be determined with confidence, given the complete opacity of its finances and the legal prohibition on disseminating or discussing this and other aspects of defence affairs, but even after six years of growth, its share of total civilian goods and services produced has grown by a few percentage points of GDP. The influence of the military goes way beyond its role as a producer. Military agencies affect markets largely through their ability to steer public contracts towards favoured private subcontractors, and to influence prices, whether by dumping cheap food imports (undercutting domestic producers) or by acting as both a principal buyer and seller of select “strategic” commodities such as steel and cement.

There are several possible drivers to this expansion. On one level, the military expanded its presence in the economy because the constraints on its expansion were weakened – particularly as large firms connected to Mubarak found themselves excluded from many major contracts. There was also the political space and will for this expansion, as President Sisi must have seen this development, especially in the early phase of his rule, as a way to ensure the support of the army to his regime.

At a deeper level, the militarization of the economy reflects the militarization of the regime, a manifestation of what appears to be an innate dirigiste tendency on the president’s part, which reflects his conviction that the civilian state apparatus lacks the commitment and effectiveness to deliver his economic goals. The expansion of the military is in this perspective closely tied to supporting the resurgent authoritarian state by pushing for public investment and implementing projects in sectors it sees as vital to the national interest, such as massive real estate or infrastructure schemes, large-scale farming, or extraction and marketing of natural resources (Adly, 2016).

There are two main concerns with the expansion of the military economy – its lack of efficiency and sustainability, and the unfair competition it unleashes on the private sector.

The oldest part of the military economy, the defence industry, demonstrates this. Its 30-odd companies are plagued by inefficiency and waste, under-utilization of capacity, and low productivity, while minimal investment in research and development results in low local content and a consequent inability to increase value-added and generate exports. In 2020, most of its companies had not been profitable in at least the preceding decade.17 More generally, military companies are a relic of the inefficient state-owned enterprises that have repeatedly been on the block since the launch of the privatization programme in 1991.18 Being classified as public companies entitles them to apply commercial rules in their internal remuneration while transferring losses to the state treasury.

But unlike the hundreds of civilian public sector companies that also remained in state ownership, the military counterparts have been shielded from competition, and scrutiny, by invoking national security. The heavily subsidized military economy is fundamentally free of economic cost-benefit analysis, for example embarking on schemes such as land reclamation and large-scale fish-farming that burden water resources in a country already below the threshold of water poverty and that involve costly energy-intensive modes of water extraction and transport. The military is largely exempt from income tax, property tax, customs duties, and other government fees and levies. 19 It benefits from considerably artificially lower production costs thanks to energy subsidies, use of military transport and exemption from tolls on military-run national highways, access to cheap foreign currency, and use of virtually free conscript labour.20 Most of these large projects consume rather than generate foreign exchange, and as such, do not contribute to solving the main constraints of the Egyptian economy.

While it is clear that this increased involvement has been correlated with a lack of private sector investment, the cause and effects are hard to disentangle. On the one hand, Sisi may have encouraged the military to expand to compensate for a weak private sector supply response, continuing even after 2015, when the regime was stabilized and did not depend as much on its alliance with the army to survive. His approach reveals disappointment and impatience with a private sector whose response to the investment opportunities he believes his administration has created following the restoration of security and stability to Egypt since 2013 has been weak and hesitant.

The Sisi administration has made a clear break with the select businessmen favoured by former president Mubarak. Some of them have been allowed to return to Egypt or rehabilitate themselves since 2013 after reaching financial settlement with the authorities, but none have regained their privileged status. Crucially, the military share Sisi’s perception of the private sector, distrusting particularly the more globalized big businesses – since they are not as vulnerable to political manipulation or financial coercion – and keeping them at arm’s length, while favouring select small and medium companies with subcontracts – both to build a more loyal constituency and to generate opportunities for nepotism and bribe-taking.

Moreover, the private sector seems heavily crowded out by the expansion of the military economy, both directly in particular markets (especially as the military have a tendency to try to monopolize markets), and indirectly, through their reduced access to state contracts and to finance. Since 2016, the military has acquired or established significant market share in the cement, steel, and phosphates sectors, for example, although these were dominated by the private sector and already suffered from over-supply and under-utilization of existing capacity. Having been safe havens thanks to their heavy trade protection, these sectors have become increasingly inhospitable for companies that rely on importing raw or intermediate materials, whereas their military competitors have an assured market in the massive construction and cultivation projects they manage. Sisi and the military have also set their sights on agriculture, reassuring farmers in 2019 that this involvement “will not exceed 10 to 15% of the country’s overall projects.” He drove home the military’s special advantage in controlling land access and use by placing prime tourist real estate on the Red Sea coast and 47 of its islands used by private tour operators under military control. And he has actively promoted capitalization of military companies by listing them on the Egyptian stock exchange (EGX).

The ability of the private sector to compete with military interests is limited by several important advantages they possess. The Sisi administration has significantly increased the economic advantages military agencies already enjoyed over civilian counterparts in both the private and public business sectors. Besides the cost advantages cited above, military agencies and their affiliated companies are legally entitled to receive and award contracts on a sole-source basis. This gives them a massive advantage over any civilian competitors in both the private and public business sectors, since it assures them of revenue streams even in areas where they are not competitive that would otherwise have gone to civilian companies. The military is also completely free from external oversight or audit by any civilian state agency. Indeed, it dominates the most powerful audit agency in Egypt, the Administrative Monitoring Authority.21 In addition, the president has noticeably strengthened his leverage by acquiring the power to hire and fire the heads of the Authority and of other principal monitoring and judicial bodies such as the Central Accounting Organization, Supreme Constitutional Court, Court of Cassation, Administrative Prosecution Authority, and Council of State. Moreover, during recent years, the Egyptian Competition Authority (ECA) has been considerably weakened. Army companies have repeatedly refused to cooperate with the ECA in its efforts to collect data whilst investigating particular markets, even though there are many reports of army companies literally closing down competing businesses to capture their market shares.

The dominance of the army has also kept foreign investors wary.22 While Sisi particularly favours public-private partnerships with foreign investors, in large part because they are not seen to pose a potential political challenge, efforts to attract FDI have fallen flat. This is especially true when it comes to the large projects pushed by the regime, which are mainly located in area designated as “strategic zone of military importance”: the Suez Canal zone, Red Sea coast, Sinai, southern and western border regions, and the new administrative capital. FDI is in this case deterred by the absence of a legal framework governing business relations and disputes with military partners makes joint ventures involving them inherently risky. The only firms that are willing to risk the absence of a legal framework governing their business ventures are those, such as large firms from the GCC, that place trust in the political relations of their national governments with Egypt to protect them.

The legal and regulatory framework that confers both extensive discretionary power and a high degree of complexity and opacity underpins the political economy of Egypt in general and enables the military economy. This is why the Sisi administration continues to drag its feet on implementing key IMF conditionality, although these are regarded as critical for private sector growth and development: reforming public procurement, and dismantling military control over the use of state land.

In sum, the expansion of the military economy has been part and parcel of a larger political endeavour to create what may be labelled a new version of Egyptian state capitalism. In this model, Sisi sees the private sector as a subordinate actor and treats it primarily as a source of capital for state schemes rather than a driver of economic growth and development, whose autonomy and initiative the state should seek to enhance.

Deteriorating social conditions amidst non-inclusive growth

If one takes the socio-economic factors fully into account, in addition to the state of decay of the private sector, the current situation is meaningfully more precarious and fragile than any past episode of cyclical recovery, including the cycles presided over by the Mubarak regime.23

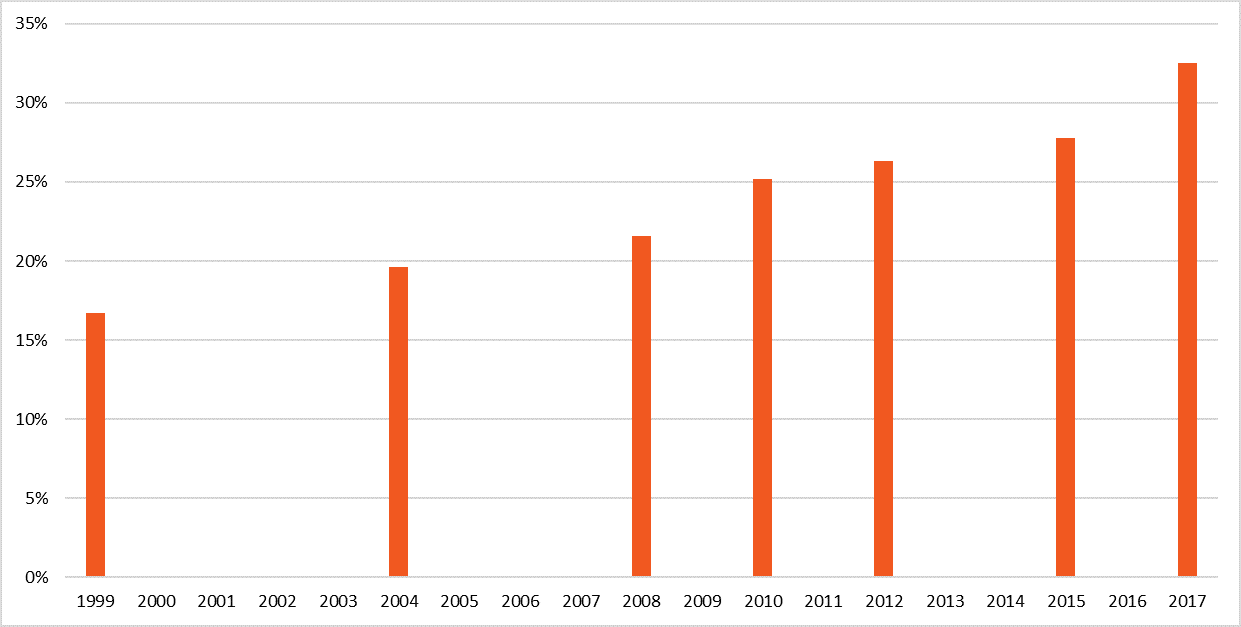

The modest growth rate has not delivered for the poor or the middle class. Poverty has not fallen – in fact, it has continued to rise, from 30% in 2012, to 33% in 2018 (WB 2020). But even that figure may be an understatement. The government has fixed the official poverty line at just 736 pounds ($45) a month, a figure that many deem as too low. The World Bank estimated recently that 60% of Egyptians were “either poor or vulnerable”.

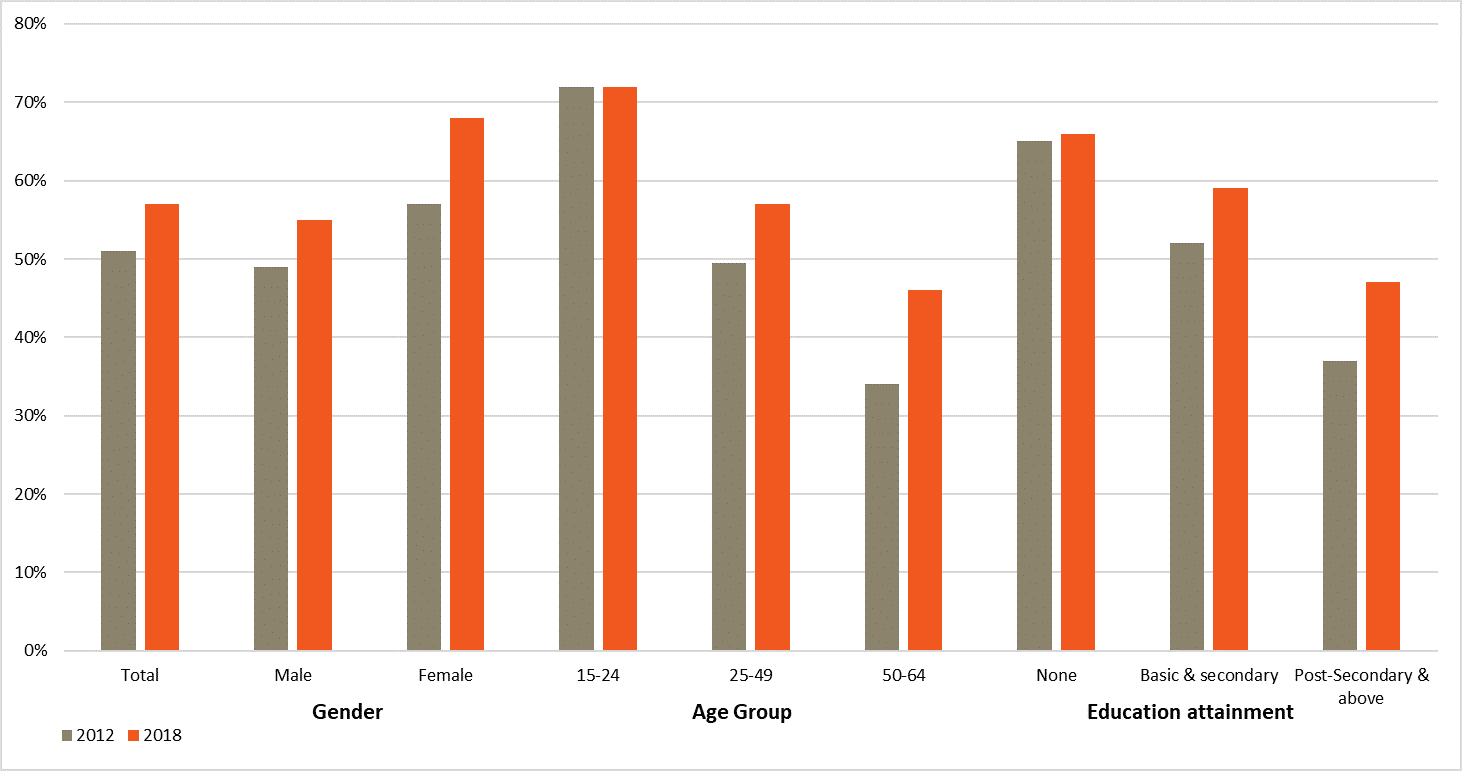

Figure 7: Share of employees below the low earning line, per type of employee (2012 and 2018)

Source: ELMPS 1988 – 2018 as calculated by M. Said, R. Galal & M. Sami, “Inequality and Income Mobility in Egypt”, Economic Research Forum, Working Paper 1368, Nov. 2019.

Subsidies were for decades the centre of Egypt’s social safety net. While many were regressive, the adopted alternatives do not appear to have adequately replaced them. The main cash-transfer schemes for the poor, Takaful and Karama, cover an estimated 9.4 million people, around 10% of the population.24 Reduction in fuel subsidies has raised transport costs. For an Egyptian at the official poverty line, a short daily trip on Cairo’s metro would now consume 25% of their monthly income.25

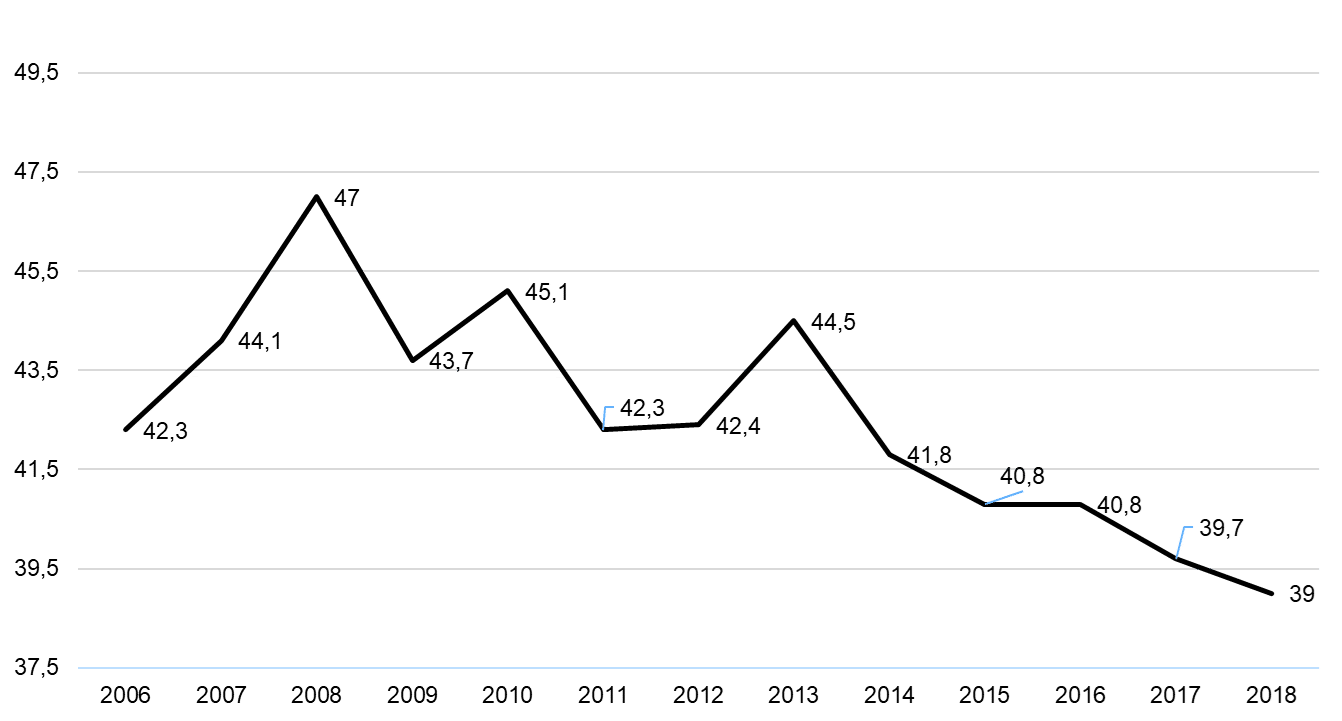

Even before the Covid-19 crisis, labour force participation was at its lowest in decades, falling from 47% in 2008, to 39% in 2018 (o/w males from 71 to 63% over the period).26 Lower participation is a sign of discouragement in the face of low demand for work and deteriorating conditions of employment. This deterioration was particularly marked among the most educated, and between 2012 and 2018. Recent events have worsened labour participation further. According to a recent study by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the COVID-19 impact on economic output will translate into temporary job losses of over 600,000 jobs between April and June 2020, especially in services and industry.27 Other studies come up with twice larger job losses.

Figure 8: Evolution of poverty rates

Source: World Bank

Note: Poverty is estimated by the Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population) and National poverty headcount ratio is the percentage of the population living below the national poverty lines, calculated from households surveys.

In parallel, adjusted for inflation, Egyptians are earning less than they did a few years ago.28 Average real wages fell by 17% between 2012 and 2018, and are now close to 1998 levels. While formal private sector and public sector workers enjoy higher real wages than informal workers, they have also experienced larger real declines in their wages – the groups particularly hit include those in urban areas, those with higher education (post-secondary and above), or high and medium skill levels, and in the private sector. This reflects, in particular, a continuation of the fall in return to education. The share of wage earners that can be classified as low – earners (i.e. below the low earnings line) increased from 51% in 2012 to 57% in 2018 – with youth the group with the highest incidence of working poor, at around 72%. Among educated wage earners, with post-secondary and above education, the share of low earners went up from 37% in 2012 to 47% in 2018. For government workers, it went up from 45% in 2012 to 55% in 2018. Across the board, Covid-19 will decrease household incomes with IFPRI estimating that average household income will decline by EGP405 (or 7.5%) per household per month between April and June 2020. The urban poor are estimated to lose 271 EGP (or -9.7% of income) during that same period.

Figure 9: Evolution of labour force participation

Source: CAPMAS, LFS DATA, ACCESSED FROM CAPMAS.GOV.EG (24 OCT. 2019)

The precariousness of jobs has continued to rise. The share of precarious employment (including irregular employment, informal employment, self-employment and unpaid family work) in total employment of young people aged 15 to 34 increased for both genders and all educational levels. However, the share of precarious employment increased more sharply for the most educated.

Figure 10: Public spending on education and health as % of GDP

Source: Ministry of Finance & World Bank, Egypt Economic Monitor, July 2019, p. 13.

At the same time as wages were being eroded, public spending on health and education has continued to fall. Based on the available statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the WHO’s Annual Report for Egypt, it appears that Egypt’s spending on healthcare as a percentage of GDP fell sharply from 4.6% in 2016/2017 to as low as 1.5% in 2017/2018, despite the government’s constitutional commitment to double the rate to 3%.29 The official reason given is that Egypt does not have the fiscal space to spend more on health and education. But given that the government has allocated or borrowed billions for spending on megaprojects, this poses questions on whether the issue is one of fiscal space or political priorities and will. Lower social spending has reduced social mobility, as the rich move to private providers, while the poor get stuck into receiving lower quality services.

Figure 11: Ease of doing business, rank of Egypt

Source: Doing Business, World Bank, various years

The coronavirus pandemic has starkly revealed the degree of deterioration of health services in the county, after years of neglect and budget cuts. The health care system is ill-equipped, poorly financed, and understaffed. Low pay has fuelled brain drain over the years – out of a total of 220,000 registered doctors, about 120,000 work outside Egypt.30 Egypt has only 1.3 hospital beds per 1,000 people – which makes it closer to the Sub-Saharan Africa average (1.2), than from that of the Arab region (1.6, excluding the high-income countries). In the most recent wave of the Arab Barometer, only 31% of Egyptians said they were satisfied with the overall performance of their government’s health care service, a near 20-point decrease since 2010.31 The Covid-19 shock was in this regard a reality check that is forcing the government to invest more in the health sector. The recently approved IMF loan is meant to support “critical spending on health, social programmes to protect the most vulnerable, and assist directly affected sectors”.32 What is not clear yet is how this extra spending will be financed in the future.

Spending on education also exhibits the same downward trajectory. The UN’s Human Development rank of Egypt has been falling for decades, going from 89 in the 1980s, to 116 in 2020 (out of 189 countries). Currently, it is estimated that only 2.4% of GDP is spent by the government on education, far lower than the 4% constitutional requirement, and than the 4%-5% levels in the 1990s and early 2000s. The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report for 2017–18 ranked Egypt’s quality of primary education 133rd out of 137 countries measured.33 Without further investment in education, including improving its quality, Egypt will be unable to move up the development ladder.34

Finally, the daunting demographic challenge persists. Egypt has a population of 100 million, growing at a rate of approximately 2%, a rate that has been rising again in recent years. The unusual reversal of previous demographic gains is present at all education levels, has been explained by the lowering of the female participation rate in the labour market, the results of the roll-back of the state, and the low growth of the formal private sector and manufacturing.35 All these factors have not changed, presaging a continuation, and even a growth in the demographic trends. Currently, more than half the population is under 24, and more than a third are under 14. Egypt is estimated to need 3.5 million new jobs over the next five years – 700,000 annually.

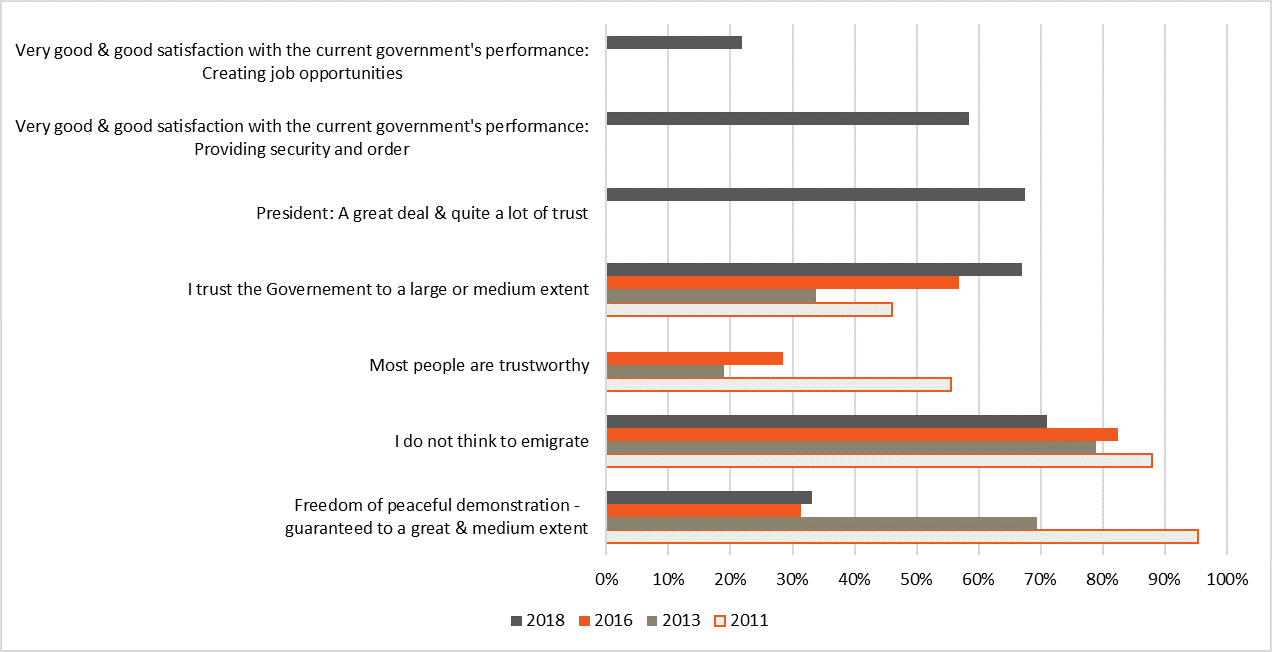

Surprisingly, in spite of these developments, public opinion, as measured by opinion polls, continue to reflect high levels of support for Sisi. While the data should be taken with a grain of salt, given the high levels of repression, they do consistently show over time a similar trend. They paint a complex picture made up of both support of some aspects of the regime, and opposition to others.

In the Arab Barometer data, taken before the Covid-19 crisis, the perception of the freedom to demonstrate (“guaranteed to a great or medium extent”) has fallen from an all-time high of 90% in 2011, to 60% in 2013, and to 30% currently, since 2016. At the same time, 68% trust the president “a lot or a great deal” in the last Arab Barometer, more than in most MENA countries. This is a remarkable recovery after the tumultuous years of 2011-13. But one also observes a slow fall in trust in government over time. How to explain these seemingly contradictory trends?

Figure 12. Opinions over time, from the Arab Barometer

Source: Arab Barometer (www.arabbarometer.org)

The answer seems to lie in the regime’s ability to reduce physical insecurity, during a period where the region was buffeted by wars and unrest – a sense of insecurity further manipulated by the state-controlled media outlets that repeat the mantra that Egypt evaded the fate of Libya and Syria. The Arab Barometer opinion polls reveal both improved levels of personal security, together with a perception of rising economic insecurity. The first variable (the Government “does ensure/fully ensure” providing security) shows a remarkable recovery to nearly 80% since 2016 (in parallel with the explosion of armed conflicts in Syria, Libya, and Yemen), after a deep fall to only 19% in 2013. But the second variable, the perception of economic insecurity has remained high. Only 20% are satisfied with the government effort to create jobs (good/very good) in the last Arab Barometer.

So far, therefore, it seems that personal security still trumps economic security, but that this is eroding. So, how long can this last? At the same time, social tensions can be seen in the collapse of social trust. When asked if other people can be trusted, only 30% responded yes in 2019 as opposed to 55% in 2011 (“Most people can be trusted”). While 10% were considering emigration in 2011, the figure has jumped to a significant 30% in the latest wave. These figures point to a catch-22 situation. Any easing of the police state before easing the social tensions from economic hardship can destabilize the system, but any further measures to crush dissent feeds into more economic hardships and as a result more built-up resentment.36

Repressing dissent and participation: The absence of civic space

The rising level of social grievances has been contained in parts by a sharp rise of repression, unseen since the “war on terror” of the 1990s. Under Mubarak, Egyptian civil society organizations operated in an environment of limited freedom and selective repression, but at least there was some space for participation and debate.37 While Mubarak ensured that civic mobilization did not cross certain red lines, and maintained Egyptian NGOs in a state of legal limbo, a relatively vibrant circle of NGOs emerged in the 1990s and early 2000s. By 2011, there were approximately 30,000 officially registered civil society organizations active in Egypt – most of which focused on charitable work and service provision in areas such as health, education, and welfare.38

In contrast, under Sisi, Egypt’s government and security services undertook a comprehensive campaign to shrink any civic space. The military’s initial crackdown targeted the Muslim Brotherhood but very quickly their campaign of repression targeted an ever-widening range of journalists, activists, and protesters under the pretext that they threaten public order or national security. Expressing grievances or criticisms of economic policies became impossible. The clampdown has recently extended to doctors and journalists who criticize or question the official response to Covid-19.

The government shut down independent media and expanded its ownership or control of most media outlets – the intelligence services have even purchased independent media outlets via the company Eagle Capital – making it impossible for any grievances to be aired through traditional media.39

Sisi basically outlawed protests and turned against NGOs and labour unions. 40 The authorities punished human rights activists and labour defenders with arrests, disappearances, beatings in detention, intimidation by State Security officers, withholding of salaries and benefits, mass firings and trials in military courts.41 The 2016 murder of Giulio Regeni, an Italian student who had been conducting research into Egyptian street vendors, was yet more evidence of the extreme repression facing the labour movement in Egypt.

The state set its sights on the Egyptian Federation of Independent Trade Unions (Al-Ittihad al-Masri lil-Naqabat al-Mustaqilla, EFITU),42 which operates as a large umbrella of non-governmental labour unions, and sought to bring it back under the umbrella of the government-run labour union syndicate, the Egyptian Trade Union Federation (Al-Ittihad al-‘Aam li-Naqabat ‘Ummal Masr, ETUF), and downsize workers’ expectations for better labour rights more generally.

Sisi has also shut down traditional channels of communication between state and society that Mubarak relied on to absorb and/or appease social grievances before they escalated. Two of Mubarak’s channels were the-then ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) and the elected local councils. These two institutions were dissolved for being corrupt – at least in part reflecting the “revolutionary” demands coming from Tahrir Square – but nothing has replaced them since. The Nation’s Future Party, also known as Mostaqbal Watan, was founded in 2014 by the Egyptian Military Intelligence as an attempt to recreate the experience of the NDP.43 While it has grown to become one of the largest political parties, it is still perceived as cut off from any grassroots movement and does not represent a pillar of governance. A series of high-level resignations in March 2020 raised further questions about the internal workings of the party and its ability to function independently of intelligence agencies.

Elected local councils were dissolved in 2011 and no new elections have been held since. The elected councils never acted as democratic or representative bodies under Mubarak, but they permitted, through their clientelist networks, to channel local grievances and distribute services. In their absence, there is a gap in relaying information from the local level to the central authorities. Sisi has tried to channel some of the energy of youth by recruiting some of them to a platform called the Youth in Political Parties (Tansiqiyyat Shabab al-Ahzab wal Siyaseyeen). The platform, created in April 2018, attempts to bring together young members from different political parties, behind a “unifying national project.” The scale of this initiative remains modest so far.

As a result, the Sisi regime has a limited toolbox to float grievances and act upon them. There are basically no shock absorbers, and any criticism is quickly perceived and dealt with as a security threat. The authorities’ overreach to the small protests that manifested themselves after Mohamed Ali, an Egyptian businessman who accused el-Sisi of wasting public funds on vanity projects, is an indication of the brittleness of the situation.

The overall picture that emerges is that of a society where most modes of organization and representation have been repressed and therefore unable to push for needed internal reforms, but where public authorities – despite having crushed all forms of dissent – feel constantly insecure and consequently over-rely on force to tackle any challenge.

Conclusions

Going into the Covid-19 pandemic, the Egyptian economy was already more brittle than its apparent successful stabilization would suggest. The economic situation has since worsened as Covid-19 affected foreign capital flows and domestic consumption. While Egypt has the reserves and international political and financial backing to overcome short-term bumps, the country presents serious fragility in the medium term if there is no change of course.

Although there are no signs that suggest an abetting trajectory in the military involvement in the economy so far, there are strategic internal reasons that should prompt Egypt to start changing course. The current situation is now on a clearly unsustainable path, and it has become imperative for Sisi to start reducing the economic role of the army in the economy. Moreover, by now that the new regime has been consolidated, President Sisi’ strategic calculations should change. The current support for military businesses is increasingly threatening the sustainability of the regime for at least two reasons: the military productivity in civilian areas has always tended to be low; and the army needs to be reoriented towards pressing security needs, as evident in the challenges posed by a quasi-insurrection in the Sinai, and by the rising importance of insecurity outside Egypt’s borders, in Sudan, Libya, and Yemen.

The central question then becomes that of the regime’s willingness to widen participation in political affairs, and relatedly, to get the private sector playing a more central role in the economy.

The constitutional amendment of 2019, which ensured the prolongation of Sisi’s mandate till 2034, and enshrined the role of the army as the “protector” of the democracy, the coming end of the period of large state projects, and the increased predation by the military of the private sector could have marked an inflexion point to widen the political and social conversation. But so far, the regime in Cairo feels no need to compromise on anything, and its international and regional backers are not exerting any pressure on it to change course.

This is short-sighted. While the current situation may seem stable in the short term, it is stability with a weak basis. The economic situation – weak to begin with – and getting worse due to Covid-19 requires a strategic change in course. Either a process of gradual reform led from the top that would allow for real participation or the alternative may be a social explosion down the line – an explosion made more likely by the absence of any shock absorbers.

Egypt’s main asset, which is also a liability, continues to be that its “too large to fail” – but can political dividend/rent be expected to continue at the same level from the GCC and the West, in the post-Corona environment? Are we looking at a situation where “too big to fail” turns eventually into “too big to float”?

International institutions and Western governments should begin conversations with Egypt about the need to reform economically and politically. At the end, the most convincing explanation for the lack of long-term progress in Egypt is its geostrategic position, acting as a resource curse. If that is the case, breaking the curse will have to start in foreign capitals. There is a need for more principled advocacy on human rights as well as strategic conversations on essential reforms to stop the Army’s hijacking of the economy and to allow for a real social and economic dialogue on the country’s future. Cairo’s refusal to engage in any substantial conversation on reform issues while it gladly takes foreign funding to keep its system afloat should be challenged. It is far better to do this soon, when the situation has not yet deteriorated dramatically, since from experience, when the situation deteriorates, support is focused on temporary fixes that fail to address any long-term vision.

*The paper benefitted enormously from a day-long round table discussion with Egypt specialists organized by the Arab Reform Initiative, and the Paris Sciences et Lettres, Arab economy Chair, in Paris, in February 2020. We would like to thank in particular Amirah El-Haddad, Robert Springborg and Kevin Carey for their suggestions, and Vladimir Najman for research support.

Footnotes

2.The IMF loan will focus “on addressing the immediate crisis needs including critical spending on health and social programmes to protect the most vulnerable”. See imf.org

3. imf.org

4. In 2020, the yields were for 40, 12, and 4 years notes: 8.875; 7.625%; and 5.75 respectively. In contrast, Egypt 2019 borrowings for similar maturities were respectively: 8.15%; 7.05%; and 4.55%. This needs to be compared with an Emerging markets investment grade rate of 3%. See: worldgovernmentbonds.com

5. ft.com

7. apnews.com

8. To continue the comparison with the 1991 reform, the fiscal adjustment then was dubbed “stealth reforms”, as they proceeded very gradually, such as by shrinking the size of bread rather than increasing its price. In fact, Mubarak spent his whole presidency gradually reducing expenditures – they were at 65% of GDP when he took over in 1981, and they fell gradually under his reign to 25% GDP by the early 2000s.

9. See, for example, El-Haddad, Amirah. “Redefining the social contract in the wake of the Arab Spring: The experiences of Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia.” World Development 127 (2020): 104774; and Diwan, Ishac, Philip Keefer, and Marc Schiffbauer. “The Mechanics, Growth Implications, and Political Economy of Crony Capitalism in Egypt.” Crony Capitalism in the Middle East: Business and Politics from Liberalization to the Arab Spring (2019): 67.

10. transparency.org

11. Diwan et al 2020 op-cited.

12. Diwan et al 2020 report that in 2010, politically connected firms owned by 32 cronies closely affiliated with the Mubarak regime received over 90% of the credit extended by the banking sector to the private sector.

13. Diwan et al, 2020, op-cited.

14. Abul-Magd, Zeinab, 2015, “Egypt’s Military Business: The Need for Change,” Middle East Institute, mei.edu

15. In this, its experience was similar to that of the military forces in Sudan, when a drop in oil revenues around 2010 pushed the army to expand its own companies dramatically. In contrast, the military in Algeria, which derives its revenues from oil exports, has refrained from massive participation in the economy.

16. According to military spokesperson Colonel Tamer Rifa’I, in a television interview, September 2, 2019 youtube.com

17. Admissions by then minister of Mohamed al-‘Assar cited in Abdel-Rahim Abu Shameh, “Minister of Military Production: 10 Billion Pounds Increase in Ministry’s Activity Compared to Last Year,” al-Wafd, November 20, 2017, bit.ly; and in Hamdy Mubaraz, “Minister of Military Production: We Target 12 Billion Pounds in 2018,” al-Alam el-Youm, March 5, 2018, bit.ly.

18. See Abdel Latif Wahba Tarek El-Tablawy, “Egypt Suspends State-Company Stake Sales Due to Virus Turmoil,” Bloomberg Quint, June 29 2020, bloombergquint.com

19. The law states that the military does not have to pay VAT on goods, equipment, machinery, services and raw materials needed for the purposes of armament, defence, and national security. But the Ministry of Defence has the right to decide which goods and services qualify and civilian businessmen complain that this can leave the system open to abuse. See: reuters.com

20. As indicated by the detailed review in Yezid Sayigh, Owners of the Republic: An Anatomy of Egypt’s Military Economy. carnegie-mec.org. [FOR ARABIC: carnegie-mec.org]

21. Jessica Noll, Fighting Corruption or Protecting the Regime? Egypt’s Administrative Control Authority, Project on Middle East Democracy, February 6, 2019. pomed.org

22. A commercial officer at a Western embassy told Reuters in 2018 that foreign investors were reluctant to invest in sectors where the military is expanding or in one they might enter, worried that competing against the military with its special privileges could expose their investment to risk. See: reuters.com

23. Others have made this point. For example, see Zuaiter – linkedin.com.

24. The “Takaful” programme gives monthly conditional pensions to vulnerable families. The “Karama” part of the programme gives non-conditional pensions to poor, elderly citizens above 65 years of age and citizens with severe disabilities and diseases as well as orphans. worldbank.org

25. economist.com

26. H. Nazier & M. Amer [2020], “Unemployment in Egypt: Trends, Causes and Recommendations.”

27. ifpri.org

28. M. Said, R. Galal & M. Sami, “Inequality and Income Mobility in Egypt”, Economic Research Forum, Working Paper 1368), and is based on the EMLP data.

29. linkedin.com

32. imf.org

33. weforum.org

34. timep.org

35. Kraft, Caroline. (2016) – Why is Fertility on the Rise in Egypt? The Role of Women’s Employment Opportunities; _Giza; Report N°1050

36. Adly, Amr, 2016, “Egypt’s Regime Faces An Authoritarian Catch-22,” carnegieendowment.org

38. Ehaab Abdou et al., “How Can the U.S. and International Finance Institutions Best Engage Egypt’s Civil Society?” Brookings Institution, June 2011, brookings.edu; and Herrold, “NGO Policy in Pre- and Post-Mubarak Egypt.”

39. madamasr.com

40. A 2014 presidential decree placed large parts of Egypt’s civilian infrastructure under army jurisdiction, meaning that anyone demonstrating outside a civilian government building without permission can be tried in military court. Patrick Kingsley, “Egypt Places Civilian Infrastructure Under Army Jurisdiction,” Guardian, October 28, 2014, theguardian.com.

42. The EFITU, which grew out of the workers’ movement during the Mahalla strikes of 2006 and was legalized in 2011, became one of the more important opposition forces during the 2011 uprisings.