Egypt Media in International Indices and Reports (2020)

This report addresses the situation of the press, media, and freedom of expression in Egypt a year before issuance of the 2020 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in April 2020. The report reviews the index’s conclusions about Egypt along with reports of a number of other international indices that evaluate the state of press and media in Egypt among other issues.

The report reviews the Freedom in the World 2020 index, compiled by Freedom House, that assesses the situation of freedom and democracy in the world, while mainly relying on the situation of the media as an important indicator for measuring freedom and democracy. The Freedom in the World 2020 provides significant additions to this report with respect to the situation of the press, media, and freedom of expression in Egypt, where it raises 15 questions about the freedom and independence of the media, as well as people’s freedom of expression in general.

The significance of this report also lies in the fact that it deals with the situation of media in Egypt through reviewing key international indices and reports, with the aim of drawing an overall picture of Egypt in the world’s eyes to help researchers, decision makers and policymakers concerned with Egyptian affairs, both at home and abroad, understand the Egyptian reality and possibly extract corrective actions.

Introduction

Since the military coup in Egypt in 2013 until today, the regime has been pursuing militarization of the State via enactment of laws and regulations and even amending the Constitution to concentrate power in the hands of the army at the expense of the civilian life, whether politically, economically, or socially. Therefore, the relationship between the regime and the people is characterized by tension and fear on the part of the people, and stalking all that is civilian on the part of the regime. However, in this struggle, the regime always has something to hide from the people.

Manifestations of this situation appear in all events and practices and control media systems, means, policies, and mission. The argument of “protection” and “national security” has become the title for all measures taken by the regime and its pretext to impose restrictions and enact repressive legislation, and a cover for the regime violations against freedom of the media, as well as an excuse to prosecute and punish critics of the regime.

The events that took place in 2019 were important and decisive, some of which strategically affected the political system such as the amendment of the Constitution and the death of former Egyptian elected President Mohamed Morsi in prison and its implications, in addition to some events related to blocking access to information and concealing facts, most notably:

1- In April 2019, Egypt witnessed amendment of the Egyptian Constitution that further concentrated power in the hands of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and authorized him to remain in office until 2030. The amendments also undermined the independence of the judiciary and strengthened the military’s role in civilian governance, as it was granted the authority to protect “democracy” and other forms of perpetuation and concentration of power for the military. Meanwhile, the regime gagged dissidents, blocking 34,000 websites to prevent blogging against constitutional amendments, and obstructed participation in the popular campaign against the Constitution changes, “Batel” (void), which was able to collect 680,000 signatures against constitutional amendments, despite the blockade imposed on it.

2- In June 2019, Egypt witnessed the demise of former President Mohamed Morsi in the courtroom, amid suspicion of being deliberately assassinated by the regime, and the people were prevented from attending his funeral. Despite the international media’s interest in and coverage of the event, the news of Morsi’s death was broadcast in Egypt through a unified 42-word-statement that was read out in official media outlets. There were directions to ignore coverage of the event whether positively or negatively; and Morsi’s death news was published in the internal pages of newspapers, not in the headlines, in ignorance of the citizen’s right to access to knowledge, and to avoid raising debate and public interaction that may be harmful to the regime.

3- September 2019 witnessed the climax of a media campaign launched by the Egyptian actor and contractor Mohamed Ali highlighting Sisi’s corruption and economic mismanagement, especially the so-called scandals of presidential palaces, where Ali had launched the campaign from Spain through video clips broadcast via social media over months. The campaign was able to penetrate the media blockade imposed by the Egyptian regime, where social networking sites interacted with it, and was supported by political and popular forces. The campaign escalated as Mohamed Ali called upon people to take to streets and demonstrate against the regime in what was known as the September mobilization, to which the regime responded by turning central Cairo to military barracks. In response, the authorities detained thousands of people and censored online speech.

4- In October 2019, the Italian journalist and former human rights activist FranceSca Borri was denied entry to Egypt to cover the mobilization. Borri had covered the assassination of Italian researcher Giulio Regeni by the Egyptian security forces. The aim of the Italian journalist’s visit was to cover peaceful demonstrations that erupted, not in response to calls from traditional opponents of the regime, but rather upon a call from a regime insider, as Borri said in an interview with Al Jazeera via Skype.

5- In November 2019, journalists Solafa Magdy, Hossam El-Sayed and Mohamed Salah were arrested from a coffee shop in Dokki, Cairo, and their car, cell phones and laptops were confiscated. A day after, State Security prosecutors detained Solafa and Mohamed pending investigation on charges of “joining a terrorist group” and “spreading false news”, while Hossam was accused of “membership in a terrorist group.”

In addition, there were many cases of detention of journalists and citizens, the closure of media platforms and the expulsion of foreign correspondents, with maintain the pre-2019 conditions, such as the continued detention and imprisonment of journalists since 2014, the continued blocking of websites, the nationalization of media institutions, and the closure of independent media outlets and means.

First: The World Press Freedom Index

About the Index

The World Press Freedom Index is compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and published annually on its official website. It is worth noting that the RSF website has been blocked in Egypt since August 2017, along with more than 500 other websites.

The World Press Freedom Index, like most indices, ranks countries in a descending order based on the level of freedom allowed, giving No. 1 to countries that best respect freedom of the press and journalists.

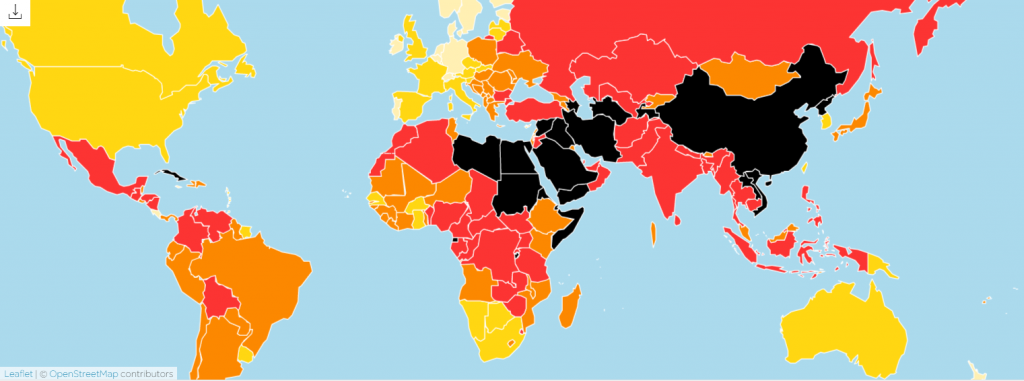

The index divides countries of the world according to their ranking into five bands, each with a different color indicating the position of the country according to the index criteria. The best countries take the white color while the worst ones take the black color, with three other colors for various degrees of freedom, as follows: The good situation (white), the satisfactory situation (yellow), the problematic situation (orange), the difficult situation (red), and the very serious situation (black).

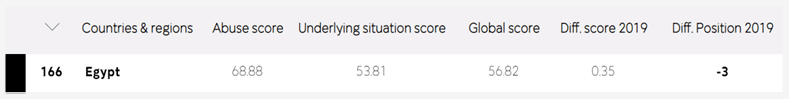

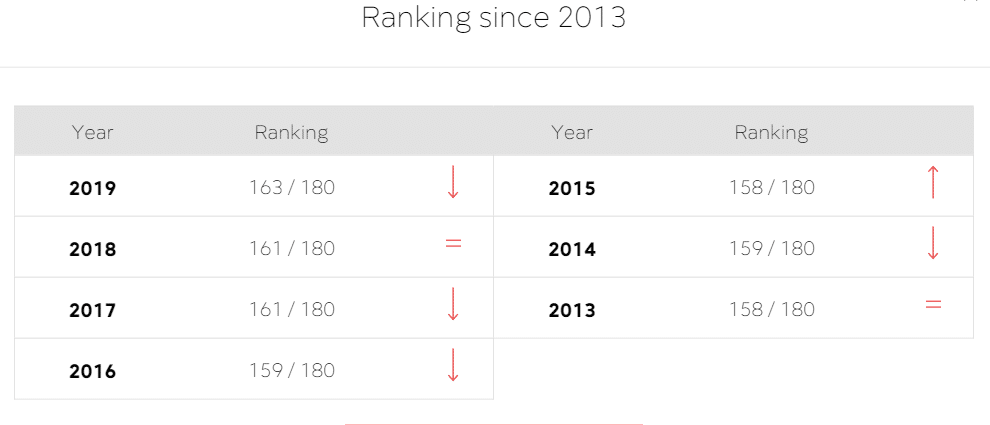

Egypt ranked 166 out of 180 countries in n the 2020 World Press Freedom Index, three points down compared to the 2019 report, where it had ranked 163 out of 180.

According to Egypt’s position on the index, the country maintains its black color on the map (i.e. very serious situation), where the media situation is moving from bad to worse over the years, as Egypt’s position on the index has moved between 158 and 166 since the military coup in 2013.

The Egypt report of the World Press Freedom Index was titled: One of the world’s biggest jailers of journalists, stating that “The press freedom situation is becoming more and more alarming in Egypt, with frequent waves of raids and arrests. Egypt is now one of the world’s biggest jailers of journalists, with some spending years in detention without being charged or tried, and others being sentenced to long jail terms or even life imprisonment in iniquitous mass trials.”

The report covered the media situation in Egypt on several axes, including controlling the entire media landscape, enacting restrictive laws, intensifying censorship and accelerating the pace of closing media outlets during elections or the referendum on constitutional amendments, and banning journalists and human rights defenders from providing independent coverage of any military operation in Sinai.

Since Abdel Fattah al-Sisi came to power:

- Most of the country’s media outlets play the Sisi tone, and the Egyptian authorities have waged a witch-hunt against journalists suspected of supporting the Muslim Brotherhood and have orchestrated a ‘Sisification’ of the media.”

- The government has bought up the biggest media groups to the point that it now controls the entire media landscape and has imposed a complete clampdown on free speech.

- While the Internet is the only place left where independently reported information can circulate, however the authorities have blocked more than 500 websites since the summer of 2017, including many news sites, and more and more people have been arrested because of their social media posts. Therefore, many media outlets have been forced to close because they could not survive economically after being deprived of online visibility.

- A draconian legislative arsenal poses an additional threat to media freedom. Under a terrorism law adopted in August 2015, journalists are obliged on national security grounds to report only the official version of “terrorist” attacks.

- New cyber-crime and media laws, enacted in 2018, enshrined government control over the media and made it possible to prosecute and imprison journalists and close websites for sharing independently reported information online.

- Meanwhile, journalists and human rights defenders are banned from much of the Sinai region and from providing independent coverage of any military operation.

- Restrictions are not only limited to coverage of military operations only, but coverage of many economic subjects, including inflation and corruption, can also result in imprisonment.

- Moreover, the presidential election in 2018 and the referendum in 2019 on a longer presidential term intensified the censorship and accelerated the pace with which media outlets are closed.

- Also, foreign media have also been targeted, with articles blocked online or attacked by officials, and reporters expelled or banned from visiting Egypt.

Index statistics

The RSF’s World Press Freedom Index 2020 only documented journalists that were killed or imprisoned due to their work, not including those who were killed or imprisoned for reasons unrelated to their work or whose connection to their work has not yet been confirmed.

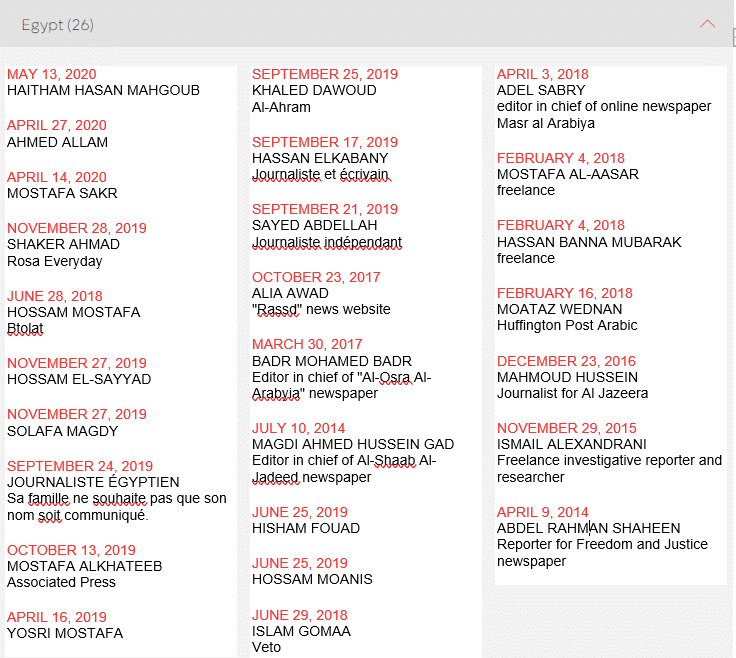

In this regard, the report documented the detention of 26 journalists for reasons related to their work, as shown in the table below:

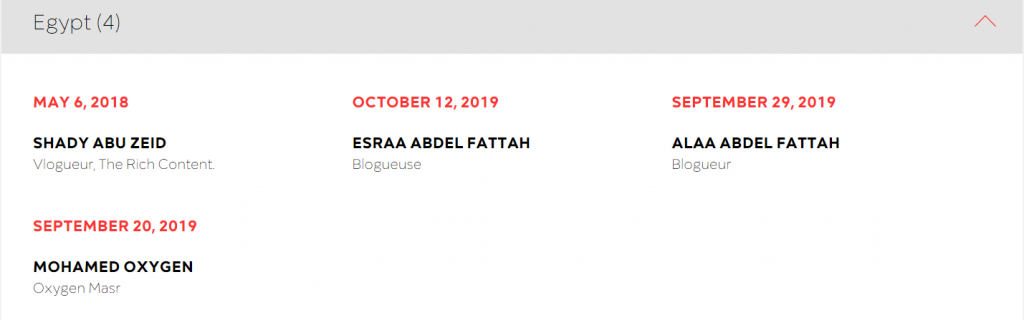

The report also documented 4 imprisonment cases for citizen journalists and bloggers, according to pictures and schedules, without documenting any deaths according to its sources this year, as shown in the table below:

Press and journalists

For further investigation of facts and expansion of research, following are 23 links of news about freedom of the press and journalists in Egypt, published by the RSF website from January 2019 to April 2020:

Second: Media in the Freedom in the World Index

About the index:

The Freedom in the World index is an annual global report compiled by Freedom House on political rights and civil liberties, and composed of numerical ratings and descriptive texts for each country and a select group of territories.

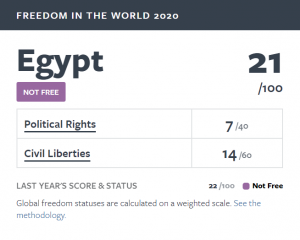

A country or territory’s Freedom in the World status depends on its aggregate Political Rights score, on a scale of 0–40 (based on a score of 4 for each of the 10 questions), and its aggregate Civil Liberties score, on a scale of 0–60 (based on a score of 4 for each of the 15 questions).

The combination of the overall score awarded for political rights and the overall score awarded for civil liberties, after being equally weighted, determines the status of Free, Partly Free, or Not Free, as shown in the table below:

The Freedom in the World 2020 index places Egypt among the countries that are Not Free, with a score of 21/100. The significance of referring to this index is the fact that it addresses the issue of media independence and freedom of expression among its criteria.

First: Civil Liberties

The index’s Civil Liberties section addresses the media issue through two main questions that include 15 sub-questions, as follows:

1- Are there free and independent media?

This question included 12 sub-questions, as follows:

- Are the media directly or indirectly censored?

- Is self-censorship common among journalists, especially when reporting on sensitive issues, including politics, social controversies, corruption, or the activities of powerful individuals?

- Are journalists subject to pressure or surveillance aimed at identifying their sources?

- Are libel, blasphemy, security, or other restrictive laws used to punish journalists who scrutinize government officials and policies or other powerful entities through either onerous fines or imprisonment?

- Is it a crime to insult the honor and dignity of the president and/or other government officials? How broad is the range of such prohibitions, and how vigorously are they enforced?

- If media outlets are dependent on the government for their financial survival, does the government condition funding on the outlets’ cooperation in promoting official points of view and/or denying access to opposition parties and civic critics? Do powerful private actors engage in similar practices?

- Do the owners of private media exert improper editorial control over journalists or publishers, skewing news coverage to suit their personal business or political interests?

- Is media coverage excessively partisan, with the majority of outlets consistently favoring either side of the political spectrum?

- Does the government attempt to influence media content and access through means including politically motivated awarding or suspension of broadcast frequencies and newspaper registrations, unfair control and influence over printing facilities and distribution networks, blackouts of internet or mobile service, selective distribution of advertising, onerous operating requirements, prohibitive tariffs, and bribery?

- Are journalists threatened, harassed online, arrested, imprisoned, beaten, or killed by government or nonstate actors for their legitimate journalistic activities, and if such cases occur, are they investigated and prosecuted fairly and expeditiously?

- Do women journalists encounter gender-specific obstacles to carrying out their work, including threats of sexual violence or strict gender segregation?

- Are works of literature, art, music, or other forms of cultural expression censored or banned for political purposes?

The report concluded that:

- The Egyptian media sector is dominated by progovernment outlets

- Most critical or opposition-oriented outlets were shut down in the wake of the 2013 coup.

- a number of private television channels and newspapers have been launched or acquired by progovernment businessmen and individuals with ties to the military and intelligence services in recent years.

- Journalists who fail to align their reporting with the interests of owners or the government risk dismissal.

- Egyptian journalists also continue to face arrest for their work. Most recently, at least six journalists were detained in the weeks following the September 2019 protests.

- The Committee to Protect Journalists reported that 26 journalists were behind bars in Egypt as of December.

- In November, security forces raided the offices of the independent English-language media outlet Mada Masr, detained 18 people on the premises for several hours, and arrested four staffers.

- The outlet had recently published an article reporting that Mahmoud al-Sisi, the president’s son, was reassigned from his senior post at the General Intelligence Directorate to a long-term position with Egypt’s diplomatic mission in Russia, apparently due to his poor performance.

- Two laws ratified in 2018 posed additional threats to press freedom.

- The Media Regulation Law prescribes prison sentences for journalists who “incite violence” and permits censorship without judicial approval, among other provisions.

- The Anti-Cyber and Information Technology Crimes Law is ostensibly intended to combat extremism and terrorism, but it allows authorities to block any website considered to be a threat to national security, a broad stipulation that is vulnerable to abuse.

- Websites that provide independent news and information are regularly blocked in practice, particularly during politically sensitive moments. For example, the online censorship monitoring group NetBlocks reported in April 2019 that internet service providers blocked access to 34,000 internet domains in the run-up to that month’s constitutional referendum.

2- Are individuals free to express their personal views on political or other sensitive topics without fear of surveillance or retribution?

Views were surveyed through three questions, namely:

- Are people able to engage in private discussions, particularly of a political nature, in public, semipublic, or private places—including restaurants, public transportation, and their homes, in person or on the telephone—without fear of harassment or detention by the authorities or nonstate actors?

- Do users of personal online communications—including direct messages, voice or video applications, or social media accounts with a limited audience—face legal penalties, harassment, or violence from the government or powerful nonstate actors in retaliation for critical remarks?

- Does the government employ people or groups to engage in public surveillance and to report alleged antigovernment conversations to the authorities?

Accordingly, the report concluded the following:

- The security services have reportedly upgraded their surveillance equipment and techniques in recent years so as to better monitor social media platforms and mobile phone applications.

- Progovernment media figures and state officials regularly call for national unity and suggest that only enemies of the state would criticize the authorities.

- The spate of arrests of government critics ahead of the 2018 presidential election and in the wake of the September 2019 protests sent a clear message that voicing dissent could result in arrest and imprisonment, contributing to self-censorship among ordinary Egyptians.

- The 2018 Media Regulation Law subjects any social media user with more than 5,000 followers to government monitoring and regulation, threatening online expression.

- The Anti-Cyber and Information Technology Crimes Law, also adopted that year, requires telecommunications companies to store users’ data for 180 days, enabling widespread government surveillance, and vaguely worded language in the law criminalizes online expression that “threatens national security.”

Following the September 2019 protests, the Twitter accounts of many Egyptian activists, including those already living in exile, were reported for suspicious activity, and suspended in a manner that suggested regime retaliation for outspoken criticism.

Second: Political Rights

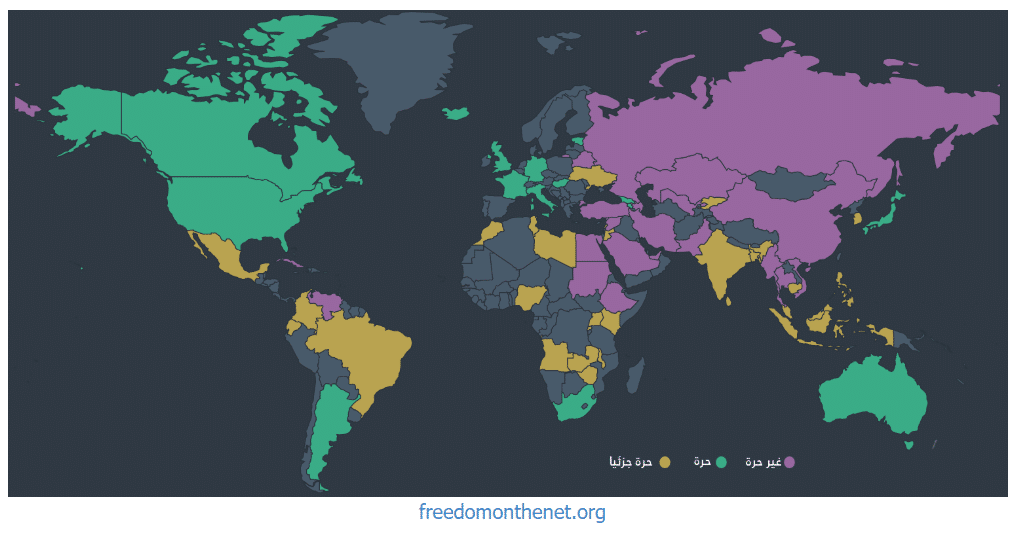

The index’s Political Rights section addresses the restrictions imposed on the Internet within the criteria of political freedoms, where it monitors the use of the world web in presenting opinions, conducting polls, campaigning and voting. The report published a map of countries of the world with relevant remarks, where it monitored blocking 34,000 websites by Egyptian authorities during the 2019 constitutional amendments to obstruct the progress of the Batel (void) campaign, which was calling for boycotting the referendum on the constitutional amendments that allow Sisi to remain in power until 2030, granting the military powers against democracy. It is noteworthy that the Batel campaign was able to collect 680,000 signatures against the constitutional amendment although its website was blocked in Egypt.

Third: Other reports

Some international reports monitor, inter alia, the state of media in Egypt, according to different criteria, with variation in degree of expansion and form of issuance, but all focus on freedom and independence of media, protection of journalists, and preservation of freedom of expression and the right to free access to information, including:

International Press Institute

The International Press Institute (IPI) is a global network of editors, journalists and media executives who share a common dedication to quality, independent journalism. The IPI condemned the continued disappearances and arbitrary detention of journalists in Egypt and called on authorities to immediately release all those swept up in a recent crackdown. It severely criticized Egypt for detaining journalists, describing it as part of a brutal clampdown by Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi to silence dissenting journalists on charges of belonging to and financing a “terrorist group” and publishing “false news” in addition to branding regime critics as terrorists and forcing news outlets to hew the official line or disappear.

The report stated that Egypt has launched an aggressive campaign against independent media since 2014, and that at least 25 journalists have been arrested since the beginning of September, according to IPI research. It added that a total of 61 journalists are currently behind bars in Egypt, making the country one of the top three jailers of media professionals anywhere in the world in 2019.

The IPI report said that during detention, the Egypt authorities systematically deny journalists rights to due process and a fair trial in the country’s compromised courts. Many are held for years without official charges and denied the right to legal counsel. Many journalists are detained over and over again.

According to IPI report, the Egyptian government continues to brutally violate press freedom by arresting journalists, storming media outlets, and blocking news websites to stifle their criticism, while the international community turned a blind eye to harassing journalists in the country. IPI Director of Advocacy Ravi R. Prasad called on the international community to hold the authoritarian regime in Egypt accountable for violating human rights, adding, “Yet again, this year Egypt retains its shameful title of one of the world’s biggest prisons for journalists. Authorities must end their current crackdown and immediately release all those who remain behind bars.”

In April, the institute urged Egyptian government to release all detained journalists amid concerns over the spread of Covid-19 in prisons.

the Egyptian government to release all journalists held in prisons due to the widespread COVID-19. “In addition to unjust detention, Egypt’s jailed journalists now face serious health risks as the coronavirus continues to spread”, IPI Director of Advocacy Ravi R. Prasad said, adding, “Egypt must prevent this unnecessary suffering – and potentially grave consequences – for these journalists and their families and ensure that all jailed journalists are freed.”

The International Press Institute along with 80 other organizations sent a joint letter to the heads of government of 10 African countries (Algeria, Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Morocco and Rwanda), including Egypt, to release all journalists held in prisons in their countries. “…for journalists jailed in countries affected by the virus, freedom is now a matter of life and death. Imprisoned journalists have no control over their surroundings, cannot choose to isolate, and are often denied necessary medical care,” the letter read.

The Sisi regime demonstrated its intolerance of criticism when the Egyptian in March revoked the credentials of The Guardian’s Cairo correspondent Ruth Michaelson for a report on COVID-19 infections in the country. On March 18, Egypt’s State Information Services (SIS) announced that it had revoked Michaelson’s credentials after a report in The Guardian, claiming that it did not meet the required press standards. “… the correspondent’s accreditation was revoked as a result of her recent article on the number of COVID-19 cases in Egypt which failed to meet ‘journalistic standards’,” SIS statement read.

The Arab Observatory for Media Freedom

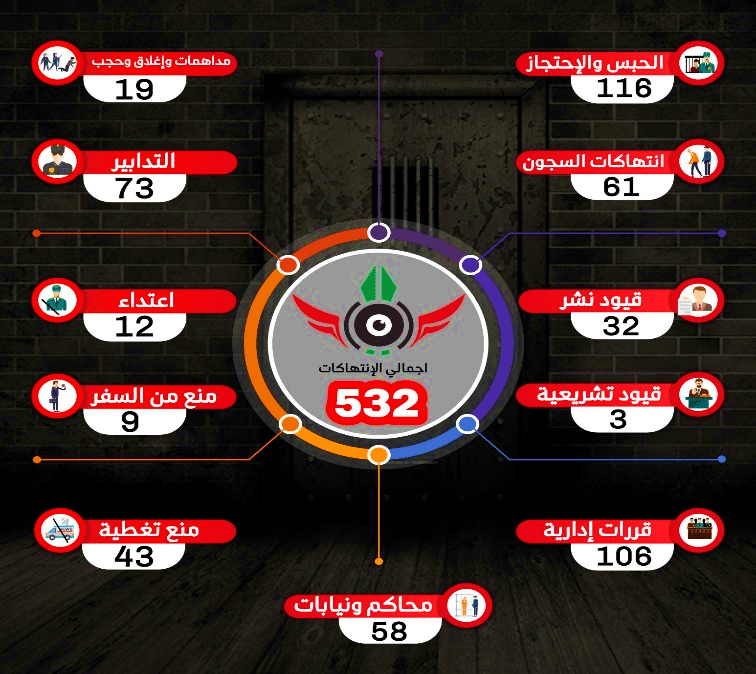

The Arab Observatory for Media Freedom (AOMF) is a specialized platform that monitors media freedoms in Egypt. The AOMF published its annual report of 2019 in January 2020, where it identified violations against journalists, bringing together a total of 532 violations (according to AOMF criteria), including 35 new cases of imprisonment for journalists and five cases of re-imprisonment pending new cases.

According to the AOMF report, cases of temporary imprisonment and detention came on top of the list of violations during the year, with 116 violations; followed by arbitrary administrative decisions (106), precautionary measures (73), prison violations (61) and prevention from coverage (43), restrictions on publishing (32), raids, closures, blocking (19), travel ban (9), legislative restrictions (3). The total number of violations suffered by female journalists reached 37 violations.

The report said the journalist Aliaa Awad is still imprisoned, despite significant deterioration of her health conditions, and the prison administration continues to refuse to allow her transfer to a hospital outside the prison to have required surgeries and receive necessary medical care.

To highlight militarization of the Egyptian media, the AOMF report was titled “Media of Officers” to highlight the army’s domination of the media system: with respect to management, means, and laws.

Conclusion

Various international reports and indices unanimously describe the media situation in Egypt as dire; amid absence of media freedoms, domination of media content, intimidation of journalists and other media actors by threats of arrest or murder.

International reports and indices also unanimously agreed that the media administration of the Egyptian regime adopts a policy of controlling the media contents; denying freedom of information; obstructing news coverage, as happens in banning journalists and human rights defenders from entering Sinai to provide independent coverage of military operations there; and buying up the biggest media groups and closure of independent media outlets to the point that it now controls the entire media landscape and imposes a complete clampdown on free speech.

The issuance of Media Regulation Law imposes further restrictions on the practice of media professionally and independently, is considered an aggregate attack on the public’s right to know, as well as freedom of expression: The Law prescribes prison sentences for journalists who “incite violence” and permits censorship without judicial approval, and subjects any social media user with more than 5,000 followers to government monitoring and regulation, threatening online expression. Therefore, buying up prominent media outlets, closing others, and blocking websites comes within the framework of controlling the media landscape as well as social networking sites, maintaining the same approach that Sisi has drawn for the Egyptian media, when he once said, “Do not listen to anyone other than me.”

The phenomenon of detention of journalists has been prominent in Egypt since the military coup against the elected president in 2013, with the aim of practicing more pressure on them and imposing more restrictions on media. The number of detained journalists documented by the above-mentioned international reports varied between 26 journalists, according to Reporters Without Borders; more than 60 journalists, according to the International Media Institute; and more than 70 journalists, according to the Arab Observatory for Media Freedom, based on various standards and documentation rules.

The Egyptian people as well as the Egyptian State will pay a high price for these restrictions imposed by the regime on media freedoms and the freedom of information, in the short, medium, and long term, as the regime pursues a consistent policy of focusing power and wealth in the hands of the army and weakening the civilian life, which creates a corrupt environment for development, as well as overloading the Egyptian people with external debts, which mortgages Egypt’s riches, capabilities and will to the outside world.

To Read Text in PDF Format Click here.