Foe Not Friend

Foe Not Friend – Yemeni Tribes and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

Nadwa Al-Dawsari*

I. INTRODUCTION

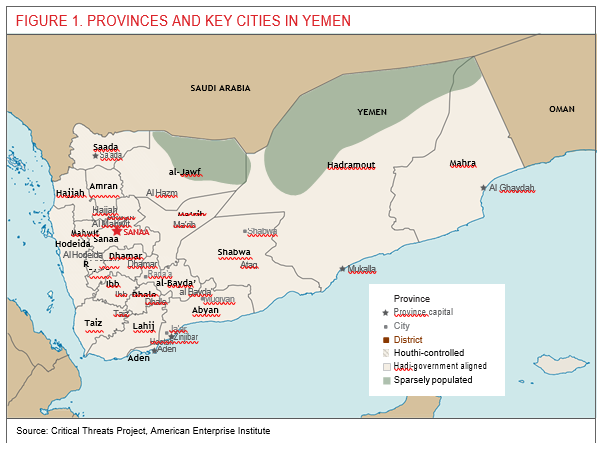

yemen’s civil war, which has killed more than 10,000 people and unleashed a humanitarian catastrophe in what is already the Arab world’s poorest country, grinds on into its fourth year.1 The war has become a complex geopolitical confrontation layered over an internal conflict.Iran is backing Yemen’s far northern-based Houthi rebels, who, along with troops loyal to former President Ali Abdallah Saleh, triggered the conflict in September 2014 when they overran the capital, Sana’a, and soon after seized large swaths of territory in northwest and central Yemen.2 The United States is arming a Saudi-led Arab coalition that intervened in March 2015 to reinstate the Houthi-toppled government of Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi, which maintains a shaky presence in parts of southern and eastern Yemen.3 (See Figure 1 for a map showing current areas of Houthi control.4)

Alongside its controversial role in the war, the United States continues to be deeply involved in counterterrorism in Yemen.Since the George W.Bush administration, the United States has tried to extinguish the al-Qaeda presence in the country, which currently takes the form of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), a merger of the Yemeni and Saudi branches of the terrorist organization.American officials have described AQAP as among the most dangerous terrorist groups due to its direct links with al-Qaeda’s global leadership and its bomb-making skills.5

The U.S.campaign has killed a sizeable number of top AQAP operatives, disrupted the terrorist group’s plots, and hindered its activities—and caused the death and injury of many innocent Yemeni civilians.But it has not vanquished AQAP.In fact, al-Qaeda’s presence in Yemen has expanded from a small cluster of jihadists in the early 1990s, to two to three hundred AQAP members at the group’s 2009 inception, to a well-funded and tenacious terrorist organization with as many as 4,000 members today.6

In trying to explain AQAP’s resilience, a narrative put forth by some Western observers and officials (and many Yemeni officials) is that tribes, key components of Yemeni society, are aligned with the terrorist group and provide it with safe havens, fighters, and other crucial support.For example, a 2016 Foreign Policy article stated that tribes are “sympathetic to al-Qaeda and opposed to the Yemeni military,” and a 2017 U.S.State Department report asserted that “AQAP used its tribal connections to continue recruiting, conduct attacks, and operate in areas of southern and central Yemen with relative impunity.”7 Some analysts describe AQAP as being “embedded” in tribes, while others depict Yemen’s tribal areas as “wild and lawless” places where the terrorist group can operate unchallenged.8 Still others point to the fact that some tribesmen are coordinating with AQAP to fight the Houthis as evidence of a tribal-militant alliance.9

This narrative is misleading.AQAP does operate in some tribal areas, and some tribesmen have joined AQAP or affiliated groups.But in doing so, they have acted independently and against the wishes and interests of their tribes.Yemeni tribes as collective entities—what tribes fundamentally are—have not backed or allied with AQAP, agreed to give its fighters safe haven, or endorsed its radical ideology; to the contrary, they have tended to see the group as a potentially serious challenge to their authority.Because of tribal pushback, AQAP has only been able to seize territory and make significant gains in parts of the country where the tribal structure is relatively weak.

Although they are opposed to the extremist group and heavily armed, tribes in areas with an AQAP presence do not automatically confront its militants with force.Tribal leaders always seek to avoid unleashing violence that could destroy the fragile security in their areas—maintaining security and social peace for their kinsmen is their top priority.They first try to pursue peaceful conflict resolution to deal with AQAP, and use force only in what they assess as particularly dire circumstances and when they have exhausted all other options.Through mediation and as a last resort through force, tribes actually have helped to limit the spread of AQAP, not abetted the group, as is sometimes claimed.

This report unpacks the dynamics between tribes and AQAP in order to argue that Yemeni tribes are not an inherent part of the problem, but instead could represent a key to countering the group effectively.The report describes the evolution of al-Qaeda in Yemen; Yemeni rulers’ relations with tribes and tribes’ governance and values; and AQAP-tribal interactions before and during the current civil war.It goes on to discuss how the excessively militarized U.S.counterterrorism approach has worsened some of the conditions in Yemen that fueled al-Qaeda there in the first place.Finally, the report offers four broad recommendations for U.S.policy toward AQAP.Ultimately, the United States should understand that interventions that are not sensitive to tribal dynamics play directly into the hands of AQAP.

II.THE EVOLUTION OF AL-QAEDA IN YEMEN

The goal of AQAP is to expel Western influence from the Arabian Peninsula and to topple the governments of Yemen and Saudi Arabia, which it sees as illegitimate Western puppets, and replace them with a puritanical Sunni Islamic caliphate.AQAP propagates al-Qaeda’s radical pan-Islamist message while expressing sympathy for specific Yemeni grievances against their rulers.Under the banner of jihad, the group has carried out attacks against Yemeni government and civilian targets as well as Western ones inside Yemen and abroad, reportedly including the January 2015 massacre of Charlie Hebdo journalists in Paris.10

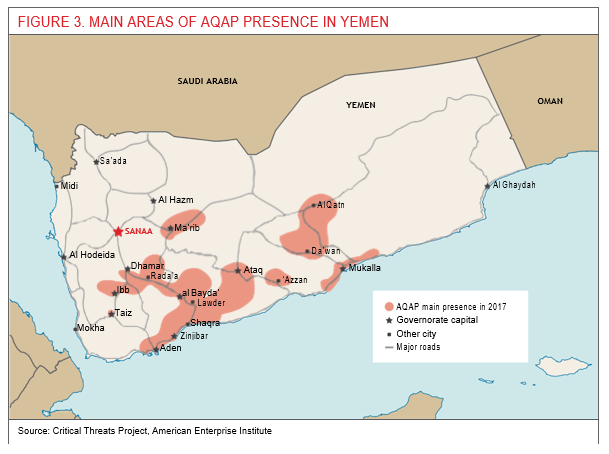

AQAP operates in cells and small groups comprised of Yemenis and some Saudis, other Arabs, and non-Arab foreigners and has networks of sympathizers across the country.Al-Qaeda has long maintained a presence in central Yemen (Ma’rib and al-Bayda’ Provinces), but AQAP is strongest in the south, especially in Abyan and Shabwa Provinces.(See Figure 3 in Section IV for a map of AQAP’s main areas of presence in 2017.) The remote terrain in these regions is conducive to the group’s activities.AQAP has also been able to capitalize on the local populations’ resentment toward the central government, long controlled by a northern-based ruling elite, for its oppression, corruption, and marginalization of their regions. (In the eyes of southern Yemenis, the Saleh and Hadi regimes, and even the Houthis, represent the northern elite.) The north-south divide is a crucial dynamic in Yemeni politics.

EARLY YEARS:RETURN FROM AFGHANISTAN

Al-Qaeda-affiliated operatives have been active in Yemen since at least the late 1980s, when thousands of Yemenis who fought the Soviet Union in Afghanistan as mujahideen returned home.Most reintegrated into civilian life, but a small number, including some close to Osama bin Laden, wanted to continue waging jihad.Many analysts consider southerner Tariq al-Fadhli to be the founder of al-Qaeda in Yemen.Al-Fadhli worked with bin Laden in Afghanistan and came back to fight the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP), the ruling party of what was then South Yemen.11

The Yemeni authorities did not view these “Afghan Arab” fighters as threats, but as heroes who pushed the Soviets out of Afghanistan, and Saleh saw them as useful.12 He turned to them to help crush his southern adversaries in the brief 1994 civil war, and after his victory, was reluctant to take action against them.13 Instead, he gave the jihadists free reign in certain areas and even appointed certain figures, such as al-Fadhli, to government positions.14 In the following decades, Saleh’s game of looking the other way or even supporting the jihadists, while convincing the West he was essential to fighting them—along with the perennial weakness of the central government—aided the spread of al-Qaeda in Yemen.15

1990s – 2005: EXPANSION FOLLOWED BY CRACKDOWN

From the early years to the mid-2000s, al- Qaeda-affiliated operatives were among several jihadist strands in Yemen.16 With their direct ties to bin Laden, and their ability to take advantage of Yemen’s permissive environment, the al-Qaeda affiliates gained skill, resources, and the capacity to carry out attacks that drew global attention.In December 1998, al-Qaeda-linked attackers killed British and Australian tourists visiting Abyan Province.Then, in October 2000, al-Qaeda bombed the USS Cole warship near Aden, killing 17 American sailors.After the September 11, 2001 attacks, countering al- Qaeda in Yemen became a U.S.priority.17 In 2002, under intense American pressure, Saleh reluctantly accepted U.S.counterterrorism assistance, including the deployment of U.S.military advisers on Yemeni soil.18 Over the next few years, the Yemeni government, with the help of the George W.Bush administration, seemingly brought the problem under control, with al-Qaeda leaders killed, expelled, or detained.19

2006: PRISON BREAK AND DEADLY COMEBACK

After 23 al-Qaeda suspects escaped from a maximum-security prison in Sana’a in early 2006, however, the group made a comeback.The Yemeni government’s official story was that the prisoners had dug a 50-yard escape tunnel using spoons and plates—but some

The naval destroyer USS Cole was attacked by an al-Qaeda suicide bomber in Aden port in October 2000.Photo: FBI

analysts believe that elements within the Saleh regime had helped them.20 Among the escapees were close bin Laden associates Nasir al- Wuhayshi and Qasim al-Raymi, each of whom went on to lead AQAP.21 (Al-Wuhayshi was killed in 2015 by a U.S.drone strike; al-Raymi, his successor, remains at large.) Following the prison break, the al-Qaeda operatives dispersed throughout Yemen, establishing a main presence in sparsely populated areas in the south-eastern provinces of Abyan (where they would open a training camp), Shabwa, and Hadramout.22 The remote terrain offered good hideouts for what at the time numbered about three hundred Yemeni and foreign militants, and were conducive to smuggling operations to finance the group.23 In the next few years, with no effective Yemeni government action against them, the jihadists strengthened their capabilities and stepped up their deadly attacks, most of which were against tourists and Western security and economic interests.24

2009: AQAP IS FORMED

In January 2009, in the wake of a Saudi government crackdown on al-Qaeda inside the Kingdom, the Saudi branch merged with al- Qaeda’s Yemeni affiliates to form AQAP, based in Yemen.25 Under the leadership of six Yemeni and six Saudi founders, AQAP was able to tap into new resources from private Saudi funding networks and improve its bomb-making skills.26 The first demonstration of AQAP’s increased lethality was its attempted assassination of Saudi Deputy Interior Minister Mohammad bin Nayef in August 2009.The threat was made even more clear on Christmas Day 2009, when AQAP came close to executing the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S.soil since September 11.A young Nigerian man trained by the group attempted to set off a bomb on board an American airliner as it approached Detroit, but was stopped by vigilant passengers.27 In January 2010, the Obama administration designated AQAP a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO).28 AQAP shot to the top of the U.S.threat list due to its close ties to “al-Qaeda Central” and its ability to build hard-to-detect explosive devices, shown also in its near-success in November 2010 in placing parcel bombs on cargo planes bound for the United States.29

2011: UPRISING AND UNREST ENABLES AQAP TO EXPAND

In January 2011, mass, youth-led, pro- democracy demonstrations erupted against the Saleh regime.AQAP took advantage of the ensuing political turmoil and the deteriorating security situation as Saleh focused on crushing the peaceful protests.AQAP expanded rapidly, and for the first time captured cities.30 To do this, AQAP assembled a new front group and insurgent force, Ansar al-Sharia (AAS).AAS recruits did not have to swear allegiance to al-Qaeda as members of AQAP are required to do, and could operate with flexibility, maintaining an official distance from the group.Through AAS, AQAP sought to build trust with the Yemeni population after al-Qaeda’s indiscriminate slaughter of Muslims in Iraq and elsewhere had badly hurt its image.31 AAS enabled AQAP to cooperate with Yemenis who might not otherwise work with it and to present a more appealing face to local Yemenis.32

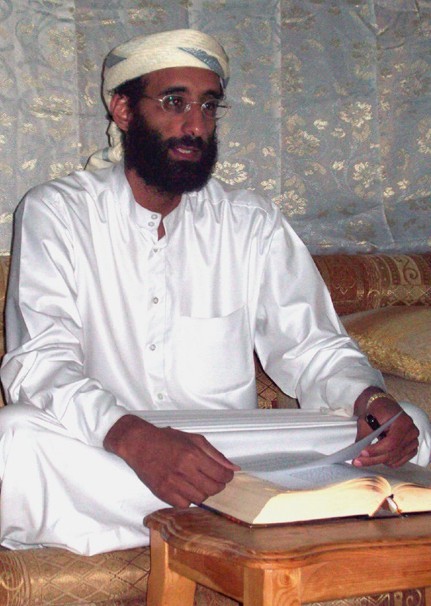

Al-Qaeda propagandist Anwar al-Awlaqi in Yemen, October 2008.Al-Awlaqi, a U.S.citizen, was killed in a U.S.drone strike in 2011.Photo: Muhammad ud-Deen/Wikimedia Commons

In March 2011, facing little resistance from Saleh’s U.S.-funded and trained security forces, AAS seized Zinjibar, the capital of Abyan Province, and the nearby city of Ja’ar, and established an “Islamic emirate.” AQAP’s AAS front delivered crucial services that the Yemeni government had long failed to bring, including security, electricity, irrigation systems, food, gas, and fresh water.Through Shari’a courts, the group swiftly resolved local conflicts that had been pending in state courts for more than a decade.33 Under AQAP control, crime disappeared.34

But AQAP’s first governing experiment turned unpopular when the group applied a repressive form of Shari’a law and used hardline tactics to maintain control.In 2012, AAS crucified a man in Ja’ar whom it accused of spying and left his body to rot in the street for days, a move that offended basic Yemeni values.35 According to researcher Katherine Zimmerman, the incident shifted public opinion against AAS.36 Abdul Latif al-Sayed, an AAS leader from Ja’ar who had joined the group out of anger at the government’s neglect of his region, said that he left because of AQAP’s shocking brutality.37 Al-Sayed went on to become the commander of the so-called Popular Committees (PCs), tribal militias that drove AAS out of Zinjibar and Ja’ar in June 2012 with help from Yemeni government forces.38

Despite this setback, AQAP retained strength and carried out a string of major attacks as popular unrest convulsed the country.An AQAP suicide bomber killed a senior military commander in June 2013, and in September of that year suspected AQAP militants took over a major army base in the south.39 In December 2013, the group launched a deadly attack against the Ministry of Defense in the heart of Sana’a, killing at least 52 people.40

2014: CIVIL WAR AND A MAJOR OPPORTUNITY FOR AQAP

After the post-Saleh political transition collapsed and civil war broke out in September 2014, AQAP exploited the security vacuum created when Yemen’s military and security forces split into pro- and anti-Saleh factions, or simply disintegrated.A key opportunity came in October 2014, when Houthi fighters, along with forces loyal to Saleh, moved into the important central province of al-Bayda’ and then in early 2015 marched into Ma’rib Province (just north of al-Bayda’), Taiz in central Yemen, and the provinces of Aden, Abyan, Lahij, Dhale, and Shabwa in the south.

After the post-Saleh political transition collapsed and civil war broke out, AQAP exploited the security vacuum created when Yemen’s military and security forces split into pro- and anti-Saleh factions, or simply disintegrated. AQAP took advantage of local outrage against the Houthi incursion and longstanding grievances against the northern elite to field AAS militants to fight the rebels.41 In addition, in the chaos, AQAP established its first presence in Taiz and Aden, long considered the most secular and liberal parts of Yemen.42 Even more concerning, in January 2015 AQAP-affiliated groups captured Hootah in Lahij Province, seized the coastal city of Mukalla in Hadramout Province three months later, and then retook Zinjibar and Ja’ar in December of that year.

The coastal city of Mukalla in Hadramout Province in Yemen’s southeast was captured by AQAP fighters in 2015 and ruled by the group until 2016, when tribal mediation helped push out AQAP. Photo: Ahmed Salem

In its second governing experiment, AQAP tried to present itself as a less brutal group.43 It did not raise al-Qaeda’s black flag or even present itself as AQAP or AAS, instead ruling through local sympathizers and using neutral-sounding names such as “Sons of Hadramout” and “Sons of Abyan.”44 It allowed government officials to go to work, refrained from targeting soldiers, and avoided enforcing strict Shari’a law.As a member of parliament who visited AQAP-controlled Mukalla soon after the takeover recalled, “Life looked normal.Nothing seemed alarming.”45

In spring and summer 2016, an offensive of local fighters recruited by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and composed of tribesmen, southern secessionists, and Salafis finally pushed AQAP militants out of these southern cities.But AQAP was not defeated.The group had made a tactical retreat, announcing that it sought to save residents from the destruction that might befall their cities if it had chosen to fight.“We only withdrew to prevent the enemy from moving the battle to your homes, markets, roads and mosques,” AQAP said in a statement posted on Twitter when it left Mukalla in April 2016.46 AQAP has maintained a presence in the countryside, and some militants have relocated to frontlines in al-Bayda’ and Taiz, where they are actively involved in fighting the Houthis.

In recent years AQAP has made important financial gains.When the group controlled Mukalla, it made USD $2 million a day from port taxes and seized more than USD $100 million from the city bank.47 This is on top of the tens of millions of dollars the group has earned from kidnappings and smuggling arms, drugs, and oil across Yemen’s southern shores.48 Looting is AQAP’s largest source of income and a key source of arms, and since 2011 it has raided military bases in Abyan, Shabwa, and Hadramout, making off with large quantities of sophisticated weapons.The group, which Yemeni officials estimate needs only about USD $10 million a year to operate, has built enough wealth to sustain its operations for years to come.49

AQAP also has become more adept at integrating itself into Yemen’s regional political struggles, thereby helping to ensure its local relevance.50 Previously many of AQAP’s commanders had operated in locations far away from their home areas in Yemen (or Saudi Arabia).In recent years, however, after U.S.counterterrorism strikes have killed several AQAP leaders, local Yemeni figures have stepped into leadership roles, making the group more decentralized.Many Yemenis associated with AQAP or AAS do not see themselves primarily as waging a global jihadist struggle.51 Instead, they see themselves more as Yemenis concerned about issues that matter to their communities, such as defending their regions from the Houthi incursion, improving services, and delivering more just governance (at least as al-Qaeda defines it).

III.THE BASICS OF YEMEN’S TRIBES

Tribes have always been a pillar of Yemeni society.Unfortunately, they sometimes are stereotyped as violent, anti-state, and an impediment to the rule of law and development, and tribesmen are portrayed as mercenaries.The erroneous narrative that backward, outlaw tribes give sanctuary to AQAP and endorse its radical ideology flows from this stereotype.As the International Crisis Group (ICG) wrote:

- [Yemen’s] common caricature is as the Middle East’s “wild west”, where gun- toting tribesmen, rugged mountains, weak governance and a deeply religious, rural population offer a breeding ground for outlaw groups.This stereotype not only risks oversimplification but can result in incorrect assumptions about AQ (that tribal areas necessarily provide safe haven, government actors are automatically the group’s foes or AQ cannot thrive equally in urban areas) and problematic, even counterproductive, policy prescriptions.52

In some cases, members of the urban Yemeni elite who lack direct knowledge of tribes and tend to look down on them have helped shape this narrative.53 In other cases, corrupt Yemeni officials have blamed tribes for the spread of AQAP in order to deflect attention from the Yemeni regime’s role in the problem and to secure Western counterterrorism aid.As ICG notes, “Western analysis…less often examines [AQAP] as a tool for Yemen’s political elite to resort to subterfuge for financial and military gain.”54 To grasp the actual dynamics between tribes and AQAP, and tribes’ strengths and limitations in responding to the militant group, it is important to understand what Yemen’s tribes are, their relationship to Yemen’s rulers, and their governance and value systems.

Yemen’s tribes are far from homogenous, but all share certain key characteristics.Tribes are territory-based entities held together by reciprocal obligations of cooperation among their members.(Kinship is a main, though not defining, attribute of Yemen’s tribal system.) Yemen has hundreds of tribes and subtribes ranging in size from hundreds of thousands to dozens of members.55 Most Yemenis identify themselves as members of a tribe: if someone is born into a family originally from a certain tribe, he or she automatically is a member of that tribe.Some urban populations identify as tribal, but Yemen’s main tribal areas—those where tribal structures and customs dominate the social order—are rural.They include parts of the north and northwest provinces of Amran, Saada, al-Jawf, Sana’a, Ma’rib, and Dhamar, and the central province of al-Bayda’.56 The tribal structure is somewhat weaker in Yemen’s west, south, and in urban centers such as Sana’a, Taiz, Hodeida, Aden, and Mukalla.

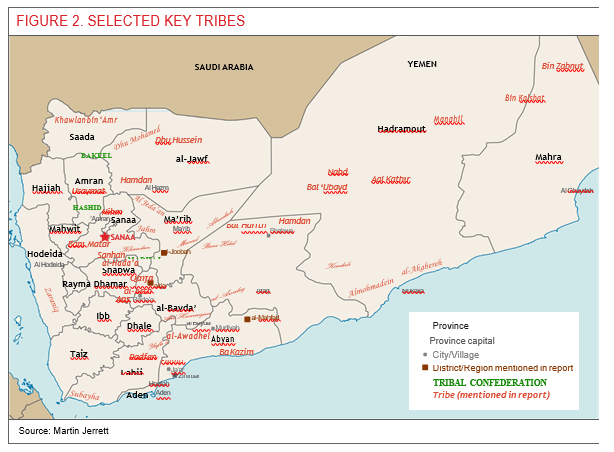

Yemen historically has had three major tribal confederations (alliances of tribes)—Hashid and Bakeel in the north, and Madhaj in central and south Yemen.57 Bakeel is the largest.These confederations represent alliances formed hundreds of years ago; today, tribesmen tend to identify more with individual tribes such as Awaleq, Khawlan, Daham, Murad, Qaifah, Yafa’a, Ans, al-Hada’a, and dozens of others.(See Figure 2 for a map showing tribal confederations and some of Yemen’s main tribes.) Yemeni tribes remain relatively strong compared to those elsewhere in the Arab world, where authoritarian police states have crushed the tribal system, and in Afghanistan, where decades of war have severely degraded it.

RELATIONS TO POWER

In order to govern, Yemen’s rulers have always forged relationships with or co-opted tribes,using both incentives and coercion (such as holding sons of tribal leaders hostage to ensure their loyalty).As tribes in the Hashid and Bakeel confederations are based near Yemen’s traditional seat of power in the north, they have enjoyed the most influence in government institutions and access to state resources.58 Centuries ago, these tribes built an alliance with Zaydi imams, theocrats from northern Yemen who ruled north and sometimes parts of South Yemen from the early 17th century until 1962, when the Imamate monarchy was overthrown by republicans.Zaydism is an offshoot of Shi’a Islam whose adherents make up about 35 percent of Yemen’s population today; the remaining 65 percent belong to the Shafi’i school of Sunni Islam.The Zaydi imams claimed authority to rule by virtue of being descendants of the Prophet Mohammed, also called Sayyids.(The Houthis, whose leadership are Sayyids, represent a hybrid of Zaydism and Twelver Shiism and claim a divine right to rule based on being descended from Prophet Mohammed.59) Hashid and Bakeel became known as the “wings of the Imam” because the imams used them to subjugate tribes in other parts of the country and paid them from the plunder of wars against tribes in the Shafi’i areas of central and south Yemen.

The late President Saleh, himself a Zaydi and a member of the Hashid confederation, consolidated and maintained power throughout his 33-year rule by appointing his close relatives and fellow tribesmen to key positions in the military and the bureaucracy.60 This form of governance by co-optation and favoritism created resentment on the part of those tribes whose regions have been left underdeveloped.

In particular, tribes in Shafi’i areas, which have Yemen’s oil, gas, fertile land, and coastline, have long watched the wealth of their regions go into the pockets of the northern ruling elite, whose areas are landlocked and resource-poor, while their own areas remain marginalized and deprived of basic services.61

Despite such frustration, however, Yemen’s tribes do not oppose the central government.Yemen’s tribal law prohibits mobilizing fighters against the state, and for this reason, tribesmen rarely attack government facilities or soldiers.62

Ma’rib tribal congregation demanding government justice after two tribesmen were killed in clashes with another tribe, August 2016.Photo: Ali Owidha

Tribal structures and government institutions have always co-existed, even collaborating at times to stop road banditry on the highways and protect public facilities.Tribal leaders and sometimes tribesmen and women serve in Parliament, the central government, and local and provincial governments.

But even before the Yemeni state effectively collapsed in recent years, the presence of the central government has always been minimal in many tribal areas.Even prior to the civil war, when government security forces were present in these regions, their functions were limited to the roles described above; they generally did little to help tribes deal with security threats such as AQAP.As for civilian government authorities in tribal areas, even under Saleh’s supposed “decentralization” system adopted in 2001, the central government maintained control over local resources and decision-making.Tribal frustration with such exclusionary rule and weak government services is widespread, and many tribes want to see an increase in government security and service-delivery in their areas.A 2011 assessment in Ma’rib, al-Jawf, al-Bayda’, and Shabwa, for instance, indicated a growing demand among tribal leaders and citizens for functioning state institutions.63

GOVERNANCE AND VALUES

Although it is sometimes claimed that tribal “lawlessness” is to blame for AQAP, Yemeni tribes are far from lawless.64 They operate according to a well-developed system of rules, rights, and obligations.Tribal members are expected to respect tribal rules and customs, to contribute to the well-being of their tribe, and to defend the tribe if needed.In return, the tribe protects them against any unjustified aggression.65

Tribes are egalitarian, not hierarchical, institutions, and as such do not have a tight command-and-control structure.Tribal leaders, or sheikhs, do not have unconditional authority over their tribes or their members.A sheikh’s legitimacy and authority depend on his ability to provide for his constituents.66 He can influence his tribesmen, but cannot force them to make certain choices.67 As the anthropologist Najwa Adra explains, tribal self-definition rests on the dual principles of respect for individual autonomy and of community responsibility.68

Tribes are governed by customary (or tribal) law, a legal code and code of conduct that regulates relationships between individuals and their tribes, among tribes, and between tribes and the state.69 Customary law is concerned with the preservation of honor—which includes hospitality, nobility, generosity, commitment to one’s word, and protection of the “weak” (women, children, andsubordinateallies).Honor also comes through demonstrating courage and solidarity with kinsmen, protecting individual tribesmen and groups from humiliation (through attacks or taking of property), and defending the tribe’s hayba (prestige).

A violation of customary law is labeled as ‘ayb (dishonor, or shame) and classified according to degree of gravity.“Black” ‘ayb, the highest offense, includes killing soldiers (the rules of major tribes prohibit them from mobilizing fighters against the government under any circumstances), murdering innocent people, and harming the public interest (such as by destroying schools, mosques, and health clinics).70 Customary law is not limited to tribal areas: it is increasingly used in Yemen’s urban areas in the face of the deterioration of official rule of law institutions.By some estimates, as much as 80 percent of the Yemeni population resolves conflicts using customary law.71

The ultimate purpose of customary law is to protect the peace within and among tribes by resolving conflicts in ways that achieve reconciliation among antagonists and preserve social cohesion.The tribal conflict resolution system relies on compromise and mutual benefit, rather than on imposed punishment or losers and winners.The mediation process involves confession of wrongdoing, apologies, praising opponents’ honor and good qualities, and forgiveness.

A key to understanding the tribal system (and tribes’ response to AQAP) is to distinguish between tribesmen as individuals, and tribes as collective units.As noted earlier, tribes are egalitarian: members make their own decisions and are not controlled by sheikhs.At the same time, the collective interest of the tribe, or community, is prioritized over that of the individual.The concept of collective responsibility is a foundation of tribal law.A crime is considered an individual act, but the consequences of the crime are borne by the entire tribe.Tribes are ultimately responsible and held accountable for their members’ criminal actions.If members violate tribal rules or otherwise bring harm to their communities, such as by engaging in violence with AQAP, their tribes can disown them.This means they lose protection and other privileges to which they are normally entitled.

To limit the escalation of violence, tribes typically avoid using force unless they have exhausted all peaceful means to mediate and resolve a conflict.They will try to avoid fighting in their own territory unless faced with an immediate threat to their authority.72 However, due to the severe degradation of Yemen’s security environment, the tribal system and its conflict resolution systems are under strain.It is increasingly difficult for tribes to manage conflicts and contain violence according to customary law and other tribal rules.73

IV.TRIBES AND AL-QAEDA

l-Qaeda’s leadership has always viewed tribes as central to power and authority in Yemen, and assumed that protection of guests and other features of tribal culture would help it establish a strong foothold in tribal areas.In 1999, senior al-Qaeda strategist Abu Mus’ab al-Suri described Yemen’s tribal areas as extremely suitable for jihad, in part due to their adherence to traditional tribal systems, their underdevelopment, and their heavily militarized culture.74 And bin Laden concluded that Yemen was the best place to rebuild al-Qaeda following the 2001 U.S.invasion of Afghanistan.Al-Qaeda’s leadership also believed that it could mobilize the tribes against the Yemeni state.In 2009, then-bin Laden deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri urged Yemen’s tribes to follow the example of Afghan and Pakistani tribes and fight their government.75 But these assumptions were incorrect.As noted, Yemen’s tribes are prohibited by their own tribal law from fighting the government, and al-Qaeda’s leadership failed to grasp other reasons for its limited appeal to tribes.

AQAP APPEALS TO SOME TRIBESMEN…

Certainly, AQAP has been able to recruit individual tribesmen (as well as urban Yemenis and foreigners).According to the author’s research and that of other scholars, most of those who have joined the group do not subscribe to al-Qaeda’s radical ideology—some of them do not even observe Islamic religious duties such as praying and fasting.76 Instead, AQAP has more often been able to recruit tribal youth who are frustrated, without good economic prospects, isolated in their communities, and vulnerable to its propaganda.AQAP speaks directly to their grievances and offers a call to action—to fight the state and other enemies.

AQAP’s narrative emphasizes humiliation, injustice, underdevelopment, corruption, andthe killing of relatives and friends and destruction of property caused by counterterrorism operations and Houthi attacks.All these themes resonate with some tribal youth in marginalized areas.

AQAP’s rhetoric has been effective at tapping into local discontent.For example, AQAP leader al-Wuhayshi announced support for the southern independence movement, which has support among many tribesmen in the south, by declaring:

- To our people in the south…what you are demanding is your right, guaranteed by your religion.Injustice, oppression, and tyranny cannot not be employed in the name of preserving unity.77

AQAP also uses poetry, a highly prized tribal art, in its propaganda.In one such poem, AQAP castigates Yemen’s rulers:

- They govern mankind without a heart; Their interests are served and they are called leaders…

Another poem exhorts Yemenis to rise up:

- …The land will not be mighty until its people fight its rulers.78

Beyond rhetoric, AQAP offers practical responses to the economic, social, and emotional needs of frustrated tribal youth.79 The group has helped tribal youth who join it build their own homes, get married, and receive decent stipends, sometimes reaching thousands of dollars.Perhaps equally important, AQAP offers them a sense of purpose and a way to become influential in their communities.80 As a former senior U.S.official who was closely involved in Yemen remarked, “I did not think that ideology was the driver to join AQAP.Rather, I thought that for some Yemenis, AQAP represented an opportunity, the only game in town.”81

…BUT SO FAR, AQAP HAS NOT APPEALED TO TRIBES

According to a 2011 field study, AQAP’s strength does not stem from Yemeni tribes—indeed, AQAP has failed to strike an alliance with any tribe.82 AQAP typically has only been able to rule—and then only for a short time—where the tribal structure is relatively weak, such as in Hadramout Province and some parts of Abyan and Shabwa.Where the tribal structure is much stronger, such as al-Bayda’ and Ma’rib, AQAP has only been able to establish a limited presence.

There are four main reasons why AQAP has not made stronger inroads into tribal areas and into tribes.First, the group’s radical vision is not at all appealing to tribes.AQAP’s wanton violence is anathema to tribal values—killing soldiers and civilians are very serious offenses in tribal law.Second, AQAP’s presence can instigate conflict within tribes, particularly between members who are sympathetic to the terrorist group and those who oppose it, threatening the fragile social order that tribes try very hard to protect. Third, the presence of AQAP in tribal areas can invite air strikes and other military incursions that cause civilian injury, death, displacement, and the destruction of property, thereby undermining tribal authority.83 Finally, Yemeni tribes look at the group as a potentially serious challenge to the tribal system.Tribes know that AQAP aspires to establish a government that would replace tribal customs with its radical version of Sharia law and relegate them to a subordinate status.

Despite all this, however, the radical group is present in some tribal areas.How, then, do affected tribes deal with this problem? Contrary to what some Western observers believe, the tribal custom of hospitality does not mean that tribes are obligated to give sanctuary to AQAP members.Hospitality is not a blanket concept in customary law.There are several categories of people to whom it may not apply, such as fugitives, adulterers, thieves, those fighting the government, those who violate tribal traditions, values, honor, and customs, and those who commit “bad acts”—including terrorists.84

TRIBES’ STRONG PREFERENCE FOR MEDIATION OVER FORCE

According to this author’s research, tribal leaders typically are distressed when their own members join AQAP or AQAP militants appear in their areas.This does not mean, however, that they automatically confront militant outsiders.As noted, tribes are cautious with their use of force.They want to avoid sparking violence that could inflame conflict and bring harm to their community.(They use the same cautious approach toward their own members who have joined AQAP, treating the decision as a choice made by individuals.) Tribes’ tolerance of AQAP ends, and tribal leaders take action against AQAP, only when tribal leaders feel that the militants pose a serious threat to the collective.Such threats could include AQAP launching attacks from tribal territory; attacking tribesmen; provoking military intervention from Yemeni authorities or others such as the United States; or seizing tribal territory.

For its part, AQAP generally has avoided being overly aggressive or confrontational with tribes.The tribes are large and heavily armed; AQAP is much smaller.The group knows that it does not stand a chance if the tribes turn against them.85 “AQAP is willing to fight 10,000 Yemeni soldiers, but not five tribesmen.The last thing AQAP would do is fight the tribes,” said Saleh bin Fareed, a prominent al-Awaleq tribal leader in Shabwa.86

To deal with threats from AQAP, tribes first employ peaceful conflict-resolution measures.Usually tribes prefer an indirect approach, using intermediaries to negotiate with the AQAP militants who are hiding out in their areas.A tribal leader may summon the head of the subtribe or clan sheltering the militants and ask him to pressure the clan to expel them.In some cases, tribal leaders may negotiate directly with the militants.The desired outcomes are to convince tribesmen who have joined AQAP to leave the group and to denounce it, or at least to agree to avoid using tribal territory to launch attacks, and to evict AQAP members who are not from the tribe.In return, the tribesmen are unharmed and allowed to live normally as members of their tribes.87

Such soft pressure can be effective.Saleh bin Fareed of al-Awaleq claims that he was able to convince hundreds of AQAP members from his tribe to abandon the group.88 And when senior AQAP figure Tariq al-Dahab, a member of al-Qaifah tribe, brought al-Qaeda into the city of Rada’a in al-Bayda’ in 2012, a mediation committee of tribal dignitaries negotiated his withdrawal.89 This followed the deployment of armed tribesmen to prevent the militants from expanding further and to protect government buildings.90 Although the tribesmen outnumbered AQAP militants, they did not use force.The tribal mediation committee convinced al-Dahab to withdraw from Rada’a a week after the miltiants entered the city.91 (Al- Dahab’s sister was married to Anwar al-Awlaqi, the American-born radical cleric and AQAP propagandist killed by a 2011 U.S.drone strike.)

Tribal mediation also played a key role in forcing AQAP out of the southern cities it captured in 2015.92 Mukalla residents said that AQAP militants withdrew from the city as a result of such mediation held days before the 2016 military offensive began.93 In Zinjibar and Ja’ar, AQAP similarly withdrew after a mediation facilitated by tribal leaders weeks before the military offensive.94 In another form of pressure against AQAP, in mid-2017 local tribes provided intelligence to the Security Belt Forces, a new UAE-backed counterterrorism force in the south, to help them track and then expel AQAP militants from al-Mahfad district in Abyan.95

Mediation is not risk-free for the tribes, however.For example, in September 2013, after negotiations with a family hosting AQAP members in Ma’rib failed, AQAP killed ten tribesmen from the Aal Ma’ili subtribe in the area.96 Then a suicide bomber attacked a Ma’rib tribal gathering where key leaders from the Abeedah tribe were meeting to forge a response to the incident and to plan for mediation that could limit AQAP’s presence in their areas.97

When mediation fails to convince tribesmen to leave AQAP or withdraw from the area, tribes usually disown them for bringing them disgrace or harm.In April 2012, sheikhs from Aal Fadhl tribe in Abyan stripped al-Qaeda in Yemen founder Tariq al-Fadhli of his status as a sheikh for facilitating AQAP’s 2011 entry into Ja’ar and Zinjibar.98 And the Qaifah tribe ultimately disowned Tariq al-Dahab for bringing AQAP militants into Rada’a.Several tribes have signed agreements to cooperate in disowning any tribesman whose family or clan refuses to stop sheltering or providing other support to AQAP.99 In mid-2012, for instance, leaders from the five major tribes of Ma’rib (Abeedah, Murad, al-Jeda’aan, Jahm, and al-Ashraf) met and signed an agreement disowning any tribesmen who join al-Qaeda.100 Following the 2016 expulsion of AQAP/AAS from Ja’ar and Zinjibar, leaders of al-Maraqisha tribe in Abyan agreed to disown any of their tribesmen who were fighting with al-Qaeda.101 And after a May 2017 U.S.military raid in Ma’rib, sheikhs from nearby tribes agreed that “any clan or family that shelters, or offers companionship to the militants or cooperate with al-Qaeda will be disowned.” The signatories included the brother of one of the AQAP suspects killed in the raid.102 In practical terms, disowned tribesmen lose the right to tribal protection and to tribal vengeance for their deaths.

Children in al-Bayda’ Province standing near the location of a January 2017 U.S.raid against AQAP.Photo: Nasser al-San’a

When AQAP has targeted tribesmen directly, tribes often avenge the attacks.For example, in August 2011, after al-Qaeda militants carried out a carjacking of an important member of the Aal Waleed tribe in Abyan, clashes broke out between tribesmen and the militants.Affiliated tribes set up checkpoints and eventually expelled al-Qaeda from the area.103 And in 2015, after AQAP planted an improvised explosive device in Shabwa province that killed members of al-Awaleq tribe, tribesmen swiftly killed the militants who were responsible.104

COMMON CAUSE AGAINST THE HOUTHIS, WHILE AQAP GAINS

Yemen’s war, the resulting humanitarian crisis, and the Houthi incursion have all put intense pressure on the tribes, weakening their resilience against AQAP and allowing AQAP to operate and recruit tribesmen more easily.

Some reports incorrectly describe local tribes’ fighting with AQAP against the Houthis in al- Bayda’ as a sectarian alliance, with “Sunni tribes” and AQAP or AAS members fighting against “Shi’a” Houthis.105 To be sure, there has been coordination between tribesmen and AQAP militants to fight their common opponent.During the war, certain tribes in al-Bayda’ have tolerated AQAP’s presence in their territory, and have shared intelligence with AQAP about Houthi fighters’ location and movement.In addition, AQAP uses sectarian rhetoric—as do the Houthis.But this author’s research has found that these al-Bayda’ tribesmen are motivated by a commitment to protect their land and homes from the Houthis than by religious hatred.Their coordination with AQAP is not a sectarian or ideological alliance but a necessary war-time tactic against a shared enemy.While there is some level of coordination between local tribes and AQAP in fighting the Houthis, they function in separate battle spaces.AQAP is usually in the mountains, mounting sudden attacks and retreating, while the tribes fight the Houthis directly.

Tribes in the regions invaded by Houthis see the rebel group as an immediate threat to their stability, authority, and social fabric.To them, the incursion seems to echo historical narratives that remain very powerful for tribesmen in these areas.In the 17th century, the imams mobilized northern tribes and forcibly added al-Bayda’ to their territory, and in the 1920s the imams’ soldiers beheaded tribal leaders there, looted their crops, and imposed heavy taxes.106

In the current war, Houthis have committed atrocities against local tribes to force them to submit to their rule.They have blown up the houses of tribal leaders and abducted, arrested, Bayda’ and cut off his head and those of some of his followers.Similarly, in the 1920s, Imam Yahya sent an army to seize al-Bayda’, which was then independent from northern Yemen, and taxed local tribes heavily and kept many tribesmen hostage to prevent a tribal rebellion.

A small village in Shabwa Province in southeast Yemen.Photo: Nadwa Al-Dawsari

and killed tribesmen—all very serious offenses according to tribal law.107 The Houthis have levied taxes and forced their own preachers into local mosques, imposing their slogan of “Death to America; Death to Israel; Curse the Jews; Victory to Islam.” All of this is extremely provocative to the tribes.108 The Houthis have further insulted the tribes by labeling those who reject their presence in al-Bayda’ as Dawa‘ish, a term derived from “Daesh” (the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State), that describes those alleged to adhere to its jihadist ideology.By contrast, from the perspectve of the affected tribes, AQAP generally has addressed them with relative respect.109 While the Houthis have routinely violated tribal honor, AQAP, in the view of these tribes, has helped to defend it by fighting to expel the rebels from tribal areas.To the tribes struggling against the Houthis, AQAP is a problem to face tomorrow, while the Houthis—whom they see as outsiders from the north seeking to grab power and rule them—are an existential threat today.110

Furthermore, the lack of support from the Hadi government and the Saudi-led coalition to tribes fighting the Houthis has caused some desperate tribesmen to turn to AQAP for help.From their perspective, this is a pragmatic choice, as they are struggling for weapons and ammunition, and AQAP offers experienced fighters, arms, and money.111

Despite their shared opposition to the Houthis, the ultimate goals of tribes and AQAP clash.The tribes’ objective is to get the Houthis out of their territory as soon as possible.They do not have an interest in fighting the rebels outside their own areas.112 AQAP, by contrast, wants to drag Houthis into tribal areas so that they can kill as many of them as possible, in order to ensnare them in a costly war of attrition using guerilla tactics.113 As a prominent tribal leader in Ma’rib explained, “Tribes want to push Houthis out.All al-Qaeda wants to do is attack and retreat.The group just creates problems and leaves.”114

V.TRIBES AND U.S.COUNTERTERRORISM POLICY

According to American officials, the long U.S.counterterrorism campaign in Yemen has degraded AQAP’s capabilities and prevented attacks against the homeland.115 But it has not made a real dent in the group’s presence, and some experts argue that U.S.policies have even helped AQAP to expand.116

The many reasons for this failure are beyond the scope of this paper to discuss in full.But part of the story is that U.S.counterterrorism policy has been too reliant on corrupt and untrustworthy Yemeni leaders, and too driven by short-term security operations, without sufficient attention to the political and economic conditions inside Yemen that gave rise to AQAP in the first place.And during the civil war, unconditional U.S.support for the Saudi-led coalition—which launched its military campaign without an exit strategy and has been responsible for large numbers of civilian deaths—has worsened a conflict that is devastating Yemen and that AQAP is exploiting.

UNRELIABLE YEMENI GOVERNMENT PARTNERS

Tribal leaders and activists in tribal areas complain that al-Qaeda in Yemen could have been exterminated a long time ago had the country’s leadership, especially President Saleh, been serious about combating the group.For a decade, the United States depended on and provided almost unconditional backing to Saleh, despite the fact that he did not actually work to rid his country of the terrorist group.This dependence ended in 2011 only because Saleh was forced from power by a popular uprising.Some U.S.officials now acknowledge that Saleh used al-Qaeda’s presence to secure a steady flow of U.S.counterterrorism aid and other support, using it to strengthen his grip on power while deploying al-Qaeda militants to eliminate his political opponents.117 A former senior U.S.official closely involved in Yemen policy in 2017 described Saleh as “an unreliable partner, someone who used terrorists as a useful tool to draw aid from the West to distribute to his family.”118 Incidents such as the 2006 Sana’a prison break strongly indicate that parts of Saleh’s regime were directly aiding the group.

Over the years, the Yemeni government’s lack of commitment to fight al-Qaeda, made most tribal leaders in affected areas reluctant to take action.According to the author’s interviews with dozens of tribal leaders, activists, and ordinary people in tribal areas dating back to 2005, often when tribes offered information to Yemeni authorities on the whereabouts and activities of AQAP militants, the government responded too late, or failed to take any action at all.“It is as if the government wants to give them enough time to escape,” said a civil society activist from Ma’rib.119 Yemeni security forces also failed to protect tribal citizens who provided intelligence about AQAP.Field research by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) found that tribal leaders who had informed the government about an al-Qaeda presence were then targeted by the group.120 For example, after helping the government destroy the cell responsible for a 2007 al-Qaeda suicide attack that killed Spanish tourists in Ma’rib, Sheikh Mohammed Rabeesh bin Ka’alan of al-Jed’aan tribe was killed by an al-Qaeda parcel bomb.121

The United States also failed to prioritize poor governance and rampant corruption within Saleh’s government as it invested significant funds in his regime.According to publicly available figures, the United States has provided Yemen about USD $1.83 billion in bilateral security and economic assistance since 2002.122 (This figure does not include funding attached to alleged significant classified programs in Yemen operated by the Defense Department.) Most of this USD $1.83 billion was for security assistance; only a small portion was meant

U.S.Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel and President Hadi entering the U.S.Defense Department, July 2013.Photo:Glenn Fawcett/U.S.Department of Defense

to address the governance and economic problems that contribute to radicalization and violent conflict.123 But the United States failed to use any of the aid as leverage to push Saleh to implement meaningful political and security reforms.Reports suggest that a large amount of the assistance was squandered inside Yemen U.S.money provided to Yemen through multilateral foreign assistance accounts.Nor does it include U.S.humanitarian assistance provided in response to the current civil war, which has reached $1 billion since Fiscal Year 2014. and that some equipment and weapons may even have ended up in the wrong hands.124 Ultimately, Saleh became a more corrupt and unpopular ruler partly due to U.S support.

Saleh’s successor Hadi also has focused on building his patronage networks and has declined to make fighting AQAP a priority.After the Popular Committees pushed AQAP out of Ja’ar and Zinjibar in 2012, Hadi refused demands from these committees and local citizens to deploy security forces in Abyan, and failed to build on the important gains made against AQAP.This mistake helped AQAP retake control of the two cities in 2015.125

AN OVERLY MILITARIZED APPROACH

Because of the Yemeni government’s poor counterterrorism record, especially during the Obama administration, the United States took the lead in containing AQAP.The preferred U.S.strategy in Yemen has been to prosecute a controversial and far-reaching air (mainly drone) strike campaign, sometimes with Yemeni cooperation.The U.S military reportedly carried out 168 air strikes in Yemen from 2011 to 2016.126 These strikes killed some AQAP leaders, but they also killed and injured many civilians in tribal areas, and caused other serious disruptions that have led Yemeni tribes to view their government with even more suspicion.

To mention just one example, a May 2010 U.S.drone strike killed Jaber al-Shabwani, the deputy governor of Ma’rib and a prominent sheikh in the Abeedah tribe, as he was closing in on a deal for AQAP militants to surrender.127 The strike created a huge backlash as his tribe felt it was a setup by elements in the Saleh regime to eliminate al-Shabwani, who was gaining influence and was known for his commitment to bring development to his long-marginalized and exploited province.His subtribe, Aal Shabwan, believed that a senior Yemeni security official had convinced the United States to carry out the strike to kill al- Shabwani.128 American military officials later acknowledged that they believed that Yemeni officials had in fact fed the United States bad intelligence in order to take out a local political leader.129 The incident created tremendous anger among tribes.A statement from the Ma’rib and al-Jawf Tribal Coalition described the incident as an “insult” and “a slap to all those who cooperate with the authorities.”130 The Aal Shabwan subtribe attacked nearby oil pipelines to pressure the Yemeni government to bring to justice those responsible for giving the strike coordinates to the Americans.131

Tribal leader Jaber al-Shabwani (shown second from right) participating in a seminar on development in Ma’rib in March 2010, two months before he was killed in a U.S.drone strike.Photo: Nadwa Al-Dawsari

In another troubling incident, in October 2014 the United States carried out air and drone strikes against alleged AQAP elements in al- Bayda’ Province, while Houthi-tribal fighting was raging on the ground.The strikes reportedly killed more than two dozen non-AQAP tribesmen who were attempting to defend their homes from Houthi rebels.132 This incident and others since have led some tribesmen to conclude that the United States is secretly aiding the Houthis as part of a larger policy to promote Iran against Sunni Arabs—a narrative that fits perfectly with AQAP’s anti-American and sectarian discourse.133

Worryingly, the Trump administration has significantly escalated military action in Yemen.During 2017, its first year in office, the administration reportedly carried out an astounding 130 airstrikes in Yemen against alleged terrorist targets—an average of 2.65 strikes per week—mainly in the provinces of al-Bayda’, Ma’rib, Shabwa, Abyan, Hadramout, and al-Jawf.134 U.S.forces also carried out their first ground raids in many years in the country, the first in Yakla in al-Bayda’ in January 2017, and a second in al-Adhlan in Ma’rib in May 2017.The raids, allegedly coordinated with Hadi’s government and supported by U.S.attack helicopters and aircraft, reportedly killed dozens of Yemeni civilians (and one U.S service member died).135 The attack sparked tribal anger against Hadi for allowing the United States to kill Yemeni civilians.136 “Shar’iyya [legitimacy, a term commonly used to describe Hadi’s government], Hawafeesh [a term commonly used to describe the Houthi/Saleh alliance], and America united to kill us,” said an angry tribesman.137 Such military actions are increasing anti-American sentiment within tribes, something that could bolster AQAP’s recruitment.138

Military raids also undermine tribal leaders’ ability to convince their members who have joined AQAP to leave the group in exchange for immunity.As explained earlier, through soft pressure, tribes have convinced many who joined AQAP to leave the group.But airstrikes and raids that kill innocent civilians simply reinforce the narrative that the United States is targeting the Yemeni tribes.

A recent episode in Ma’rib illustrates this problem.AQAP had successfully recruited three members of the small al-Ethlan clan, part of the Murad tribe, in the village of al-Joobah.After an April 2017 U.S.airstrike killed one of the three AQAP members, tribal leaders asked the clan to take strict action against the two surviving men, giving them the option to leave AQAP or to leave the area.The leaders stated that if the men chose to remain with AQAP, their tribe would disown them.The two men reportedly decided to leave AQAP but feared that the group would target them, since it kills those who leave it after swearing allegiance.“If we stayed with the tribe, al-Qaeda will kill us.If we stay with al-Qaeda, the Americans will kill us,” one reportedly said.139 Despite being open to leaving AQAP, they were killed in the U.S.ground raid in May 2017.And in al-Bayda’, many tribesmen who defected from AQAP are staying inside their homes, fearing that they will be targeted by drones.140

The United States has forged an increasingly close counterterrorism partnership in Yemen with the UAE, an influential member of the Saudi-led military coalition.141 The UAE worked successfully with local Yemeni forces to push AQAP out of major cities in the south in 2016, but its approach ultimately may be counterproductive.The botched January 2017 U.S.raid in Yakla was conducted with UAE commandos and reportedly was based on an Emirati tip that AQAP leader Qasim al-Raymi was hiding in the area.142 As noted, the raid killed many civilians, but it failed to kill or apprehend al-Raymi or any other high-value AQAP target.143

Tribesmen examine the aftermath of a drone strike in the village of al-Manein, Ma’rib Province, April 2016.Photo: Ali Owidha

UAE operations against AQAP may also antagonize the tribes.UAE-backed forces in southern Yemen, namely the Security Belt and the Elite Forces, have reportedly been involved in serious human rights abuses against alleged AQAP members and even children.144 In October 2017, hundreds of tribal leaders and tribesmen in Abyan met to discuss a response after three of their members reportedly were tortured to death while in the custody of the Security Belt Forces.145 UAE missteps and heavy- handed tactics could further alienate the tribes, and lead them to take a neutral stance toward AQAP or even push affected tribesmen to turn to the group for protection.

Vi.CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This paper has sought toexplain why the assertion that Yemeni tribes are key actors helping AQAP is incorrect.Without Yemeni tribes containing AQAP’s presence in their areas and pushing it out where it has tried to expand, the militant group might pose a greater danger.

Yemeni tribes continue to oppose AQAP.But in the current war environment, tribes (and other Yemeni citizens) face many urgent threats, of which AQAP is not always the most immediate.The current cooperation between some tribesmen and AQAP to fight the Houthis is, for the tribesmen, a tactical arrangement to defeat a common enemy, not a deeper ideological alliance.In areas where tribal resistance has stopped the Houthi incursion, the tribes have played a constructive role in getting AQAP to withdraw.Tribes will use force against AQAP, but only after pursuing tribal mediation and negotiations as their preferred—and often effective—strategies to deal with the group.

Tribes have been and can be a part of the solution in the struggle against the scourge of AQAP.But as this paper has argued, U.S.counterterrorism policy, with its heavy reliance on military action to kill AQAP leaders, has been harmful to tribesmen (and other Yemeni civilians) and complicated the tribes’ role in fighting against AQAP.And the Yemeni ruling elite long backed by Washington are directly to blame for the current war that has created conditions favorable to AQAP.

AQAP continues to pose a threat to Yemen and to the United States and its allies, and the United States will need to pursue and counter the group in a responsible fashion.The following policy recommendations are offered to the United States to adjust its counterterrorism policies in Yemen, particularly as they relate to the role of tribes.

1.Work to end the war as soon as possible.The Trump administration should work with Arab allies, the United Nations, and other members of the international community to push the warring parties to agree on a durable political solution to end this disastrous war.Ongoing conflict simply opens the door for AQAP to expand and degrades the capacity of tribes and other Yemeni institutions to prevent its spread, not to mention inflicts devastation upon Yemen as a whole.

A “quick fix” solution that simply reinstalls members of the northern elite to power, however, may be tempting to many officials, but it will fail and will plant the seeds of another conflict.A lasting political settlement forged by a wide range of Yemeni actors, not just the northern elite, is needed in order to create a more representative, just, and accountable political system.The absence of such a system is at the root of Yemen’s conflicts.

Any negotiated settlement must require Houthis to withdraw their forces from al- Bayda’ Province, where the Houthi offensive has enabled AQAP to form a relationship with tribes that otherwise would have been immune to AQAP’s influence.(The Houthis must also be required to withdraw from Taiz, where an almost three-year- long indiscriminate bombing campaign by Houthi and Saleh forces and extensive fighting between Houthis and local forces has helped AQAP to establish a presence for the first time.)

2.Do not wait until the end of the war to help Yemenis strengthen security.Act now to address local political and economic needs, especially through bottom-up approaches.In areas such as parts of the south where the fighting has abated, the United States and international partners should work with the Yemeni government to train security forces involved in counterterrorism.They should work with both local authorities and nascent security structures to create more effective indigenous security institutions and to prevent human rights violations by security forces.Yemen’s central government has a minimal presence across the country at present, but some local authorities, along with tribes, have managed to maintain a reasonable level of security in many areas.There is something at the local level on which to build, and more support is needed.

An effective approach would be to help local authorities and tribes work together to develop stronger security forces that can help to defeat or limit AQAP, as well as provide security to local residents beyond counterterrorism.Tribes avoid conflict with AQAP, in part because they lack government backup and protection.The goal would be to help build sustainable security institutions that can prevent AQAP from simply returning after its militants are expelled and that protect tribes from security threats.At the same time, civilian assistance to help local and tribal authorities in tribal areas and other regions to address humanitarian needs and improve economic and social conditions remains urgent.

3.Limit the use of airstrikes and raids against AQAP, especially in areas—such as al-Bayda’—where clashes between Houthis and tribes are ongoing.Such attacks can generate popular anger that AQAP exploits.In some cases, they have inadvertently tipped the scales against tribes in favor of the Houthis in some areas, creating anti-American sentiment and reinforcing AQAP’s narrative that the United States is supporting Iran-backed Shi’a Houthis against Sunni tribes.This narrative resonates among some Yemenis who are vulnerable to recruitment by the terrorist group.

4.Explore the possibility of rehabilitation for some members of AQAP who joined the group for economic, political, or social reasons, not due to religious deviance or ideological commitment.As explained, many tribesmen have joined AQAP out of frustration and resentment about local problems, rather than inspiration from al- Qaeda’s global vision.Rehabilitating such AQAP members would be controversial and difficult to implement, but it could pull hundreds of tribesmen away from the terrorist group.The United States could support civic and tribal groups to pursue rehabilitation programs in which Yemeni officials work with the tribes to engage in a dialogue with their members who have joined AQAP, and try to respond to the grievances that made them susceptible to the group.

—————————————————

1.“Yemen Conflict: At Least 10,000 Killed, Says UN,” BBC, January 17, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-38646066.The war has brought seven million Yemenis, nearly one-third of the population, to the brink of famine.It has caused the worst cholera epidemic in reported history, with one million cases recorded as of December 2017.See Angela Dewan and Henrik Pettersson, “Cholera Outbreak Hits Record 1 Million,” CNN, December 21, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2017/12/21/ health/yemen-cholera-intl/index.html, and United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Yemen: 2018 Humanitarian Needs Overview, December 4, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/sites/ reliefweb.int/files/resources/yemen_humanitarian_needs_overview_hno_2018_20171204_0.pdf

2.Saleh, a strongman who ruled Yemen from 1978 to 2012, was killed in Sana’a on December 4, 2017, by his former Houthi allies who turned against him.

3.Michelle Kosinski and Ryan Browne, “Trump Is ‘Fired Up’ about the Humanitarian Situation in Yemen,” CNN, December 21, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2017/12/20/politics/trump-yemen-humanitarian-crisis/ index.html.For background on the war and the Yemeni political dynamics driving the conflict, see Nadwa

Al-Dawsari, Breaking the Cycle of Failed Negotiations in Yemen, Project on Middle East Democracy, May 2017, http://pomed.org/pomed-publications/breaking-cycle-of-failed-negotiations-yemen/

4.As of January 2018, the Houthis remain in control of al-Bayda’ Province and of all the northern provinces, in addition to Hodeida Province on the western coast.Most of Yemen’s population lives in these areas.The Houthis were recently pushed out from most of al-Jawf Province in the north, and from the west coast of Taiz Province and close to Hodeida city.In the summer of 2016, they were pushed out of the whole south (Aden, Lahij, Abyan, and most of Shabwa Provinces).The Houthis have never controlled the easternmost provinces of Hadramout and Mahra.

5.Central Intelligence Agency Director Mike Pompeo, “Remarks as Prepared for Delivery at the Center for Strategic and International Studies,” Washington, DC, April 13, 2017, https://www.cia.gov/news-information/ speeches-testimony/2017-speeches-testimony/pompeo-delivers-remarks-at-csis.html; Office of the Press Secretary, the White House, “Letter from the President to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate Regarding the War Powers Resolution,” White House Archives, June 13, 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/06/13/letter-president-war-powers- resolution

6.See briefing from the Soufan Group, “The Quadrupling of Al-Qaeda in Yemen,” June 6, 2016, http://www.soufangroup.com/tsg-intelbrief-the-quadrupling-of-al-qaeda-in-yemen/.Citing U.S.Department of State Reports, the brief says that as of 2016 AQAP had some 4,000 members in Yemen.

7.Jack Watling and Namir Shabibi, “How the War on Terror Failed in Yemen,” Foreign Policy, May 18, 2016, http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/18/how-the-war-on-terror-failed-yemen/; United States Department of State Bureau of Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2016, July 2017, https://www.state.gov/ documents/organization/272488.pdf

8.See for example Farea Al-Muslimi and Adam Baron, “The Limits of US Military Power in Yemen: Why Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula Continues to Thrive,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 27, 2017, http://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/86; Rohan Gunaratna and Aviv Oreg, The Global Jihad Movement (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 134.

9.For instance, Anthony Celso writes, “Some tribes support al-Qaeda in remote parts of Yemen.AQAP has successfully embedded some of its leaders in Yemen’s tribal structure supporting northern Sunni tribes against Shia rebels [the Houthis] and assisting groups fighting the central government.” Anthony Celso, Al-Qaeda’s Post-9/11 Devolution: The Failed Jihadist Struggle against the Near and Far Enemy (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 136.

10.Hugh Naylor and Brian Murphy, “Al-Qaeda in Yemen claims responsibility for ‘vengeance’ attack on Paris newspaper,” Washington Post, January 14, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/al- qaeda-in-yemen-claims-responsibility-for-vengeance-attack-on-paris-newspaper/2015/01/14/1d83604c-9bef- 11e4-bcfb-059ec7a93ddc_story.html?utm_term=.1555bdd6b0d5

11.Tariq al-Fadhli is the son of the sultan who, during the British colonization of South Yemen, ruled

the Fadhli Sultanate in part of what is today Abyan Province.The YSP ruled South Yemen after independence, and Tariq held the party responsible for confiscating his family’s land and forcing them into exile in the late 1960s.South Yemen was ruled by a communist regime allied with the Soviet Union until the unification of North and South Yemen in 1990.For more, see International Crisis Group, Yemen: Coping with Terrorism and Violence in A Fragile State, January 2003, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and- arabian-peninsula/yemen/yemen-coping-terrorism-and-violence-fragile-state

12.International Crisis Group, Yemen.

13.After the 1990 unification, the YSP shared power with the General People’s Congress (GPC), the former ruling party of North Yemen, until the 1994 civil war, which the GPC (led by Saleh) won.

14.For instance, Tariq al-Fadhli was rewarded by being appointed as a senior member of the GPC.See Rafid Fadhli Ali, “The Jihadis and the Cause of South Yemen: A Profile of Tariq al-Fadhli,” Terrorism Monitor 7, no.35 (November 2009), https://jamestown.org/program/the-jihadis-and-the-cause-of-south-yemen-a-profile- of-tariq-al-fadhli/.Egyptian Islamic Jihad, headed by Ayman al-Zawahiri, who would go on to lead al-Qaeda after bin Laden’s killing in 2011, found a base in Yemen for a period during the 1990s.See Thomas Joscelyn, “Resolving the Conflict in Yemen: U.S.Interests, Risks, and Policy,” Long War Journal (blog), Foundation for Defense of Democracies, March 10, 2017, https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2017/03/resolving-the- conflict-in-yemen-u-s-interests-risks-and-policy.php.For more on Saleh’s dealings with the jihadists, see Bashir al-Bikr, Al-Qa’ida fi Yaman wal-Sa’udiyya [Al-Qaeda in Yemen and Saudi Arabia] (Beirut: Dar al-Saqi, 2011), and Martin Jerrett and Mohammed al-Haddar, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula: From a Global Insurgent to a State Enforcer, Hate Speech International, March 2017, https://www.hate-speech.org/wp- content/uploads/2017/03/From-Global-Insurgent-to-State-Enforcer.pdf

15.Jerrett and al-Haddar, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

16.The most prominent of these groups were the Aden-Abyan Islamic Army (AAIA) and the Islamic Jihad Movement (IJM), both of which had direct personal links to bin Laden.See International Crisis Group, Yemen, 11.

17.Azmat Khan, “Understanding Yemen’s Al Qaeda Threat,” Frontline, PBS, May 29, 2012, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/foreign-affairs-defense/al-qaeda-in-yemen/understanding-yemens-al-qaeda-threat/

18.IHS Jane’s, Jane’s Sentinel Security Assessment-The Gulf States (Alexandria, VA: Jane’s Information Group, 2012).

19.Christopher Boucek, Gregory D.Johnsen, and Shari Villarosa, “Al-Qaeda in Yemen,” panel discussion, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 7, 2009, http://carnegieendowment.org/2009/07/07/al- qaeda-in-yemen/wqa%3E

20.The “great escape” happened just months after Yemen was suspended from the U.S.Millennium Challenge Corporation development aid program, losing $20 million in assistance, and after the Bush administration

had reduced U.S.military aid to Saleh, judging Iraq and Afghanistan as more pressing terrorism priorities.See Gregory D.Johnsen, The Last Refuge: Yemen, Al-Qaeda, and America’s War in Arabia (New York: W.W.Norton & Company, 2012), 182–195.

21.Gregory D.Johnsen, “Ignoring Yemen at Our Peril,” Foreign Policy, October 31, 2010, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2010/10/31/ignoring_yemen_at_our_peril; Katherine Zimmerman, “Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula: Leaders and their Networks,” American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project, September 27, 2012, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/al-qaeda-in-the-arabian-peninsula-leaders-and- their-networks

22.Jerrett and al-Haddar, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.AQAP later established several training camps in Abyan and in the Sanhan region of Sana’a Province.See Bill Roggio, “Al-Qaeda Opens New Training Camp in Yemen,” Long War Journal (blog), Foundation for Defense of Democracies, November 13, 2009, https:// www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2009/11/al_qaeda_opens_new_t.php

23.On AQAP financing, see Yaya J.Fanusie and Alex Entz, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula: Financial Assessment, Foundation for Defense of Democracies Center on Sanctions and Illicit Finance, July 2017, http:// www.defenddemocracy.org/content/uploads/documents/CSIF_TFBB_AQAP_web.pdf

24.Al-Qaeda killed seven Spanish tourists in Ma’rib in July 2007 and ten Yemeni staff of the U.S.Embassy in Sana’a in September 2008.Robert Worth, “10 Are Killed in Bombings at Embassy in Yemen,” New York Times, September 17, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/18/world/middleeast/18yemen.html

25.See “Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula,” Council on Foreign Relations, July 19, 2015, https://www.cfr.org/ backgrounder/al-qaeda-arabian-peninsula-aqap

26.AQAP’s top bomb-maker is a Saudi national, Ibrahim al-‘Assiri.He remains at large.

27.“Al-Qaeda Wing Claims Christmas Day US Flight Bomb Plot,” BBC, December 28, 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8433151.stm

28.Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, “Designations of Al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and Senior Leaders,” U.S.Department of State, January 19, 2010, https://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/other/ des/143208.htm

29.“Yemen-Based Al-Qaeda Group Claims Responsibility for Parcel Bomb Plot,” CNN, November 5, 2010, http://www.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/meast/11/05/yemen.security.concern/index.html.“Al-Qaeda Central” is a term used by U.S.officials and analysts to refer to the main al-Qaeda group formed by the late Osama bin Laden, now led by his deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri, and reportedly based in Pakistan’s border regions.Bill Roggio, “AQAP Leader Pledges Oath of Allegiance to Ayman al Zawahiri,” Long War Journal (blog), Foundation for Defense of Democracies, July 26, 2011, http://www.defenddemocracy.org/media-hit/aqap- leader-pledges-oath-of-allegiance-to-ayman-al-zawahiri/

30.Council on Foreign Relations, “Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.” Also see U.S.Department of State,

31.Thomas Joscelyn, “State Department: Ansar al Sharia an Alias for AQAP,” Long War Journal (blog), Foundation for Defense of Democracies, October 4, 2012, https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2012/10/ state_department_ans.php

32.Katherine Zimmerman, “AQAP Post-Arab Spring and the Islamic State,” in How Al-Qaeda Survived Drones, Uprisings, and the Islamic State, ed.Aaron Y.Zelin, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, June 2017, http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/PolicyFocus153-Zelin.pdf

33.Robin Simcox, “Ansar al-Sharia and Governance in Southern Yemen,” Current Trends in Islamist Ideology 14, Hudson Institute, January 2013, http://www.hudson.org/content/researchattachments/

attachment/1139/20130124_ct14simcox.pdf; author’s interview with a tribal leader/businessman from Abyan, November 21, 2013.

34.Simcox, “Ansar al-Sharia and Governance in Southern Yemen.”

35.Mohammed Jamjoom, “Amnesty Details ‘Horrific Abuses’ in Southern Yemen,” CNN, December 4, 2012, http://www.cnn.com/2012/12/04/world/meast/yemen-amnesty-report/index.html

36.Author’s interview with Katherine Zimmerman, June 22, 2017.

37.Essam Ali Mohammed, “Yatahadath Abdul Latif al-Sayyid Qa’id al-lijan al-Sha’abiyah li Akhbar al-Youm:

Ba’ad tasreehi min al-lijan sa’a’ood li a’mali mozari’an wa ra’ii noob” [Abdul Latif al-Sayyid talks to Akhbar

al-Youm: After my dismissal from the Popular Committees I will return to farming and beekeeping], Akhbar al-Youm, accessed January 3, 2018, http://akhbaralyom-ye.net/news_details.php?sid=69196

38.Nadwa Al-Dawsari, “The Popular Committees of Abyan: A Necessary Evil or an Opportunity for Security Reforms?” Middle East Institute, March 5, 2014, http://www.mei.edu/content/popular-committees-abyan- yemen-necessary-evil-or-opportunity-security-reform.Al-Sayed is now the commander of the Emirati-backed “Security Belt” forces leading the UAE fight against AQAP in Abyan.

39.“Yemeni Army Commander Killed in Suicide Blast,” al-Jazeera, June 18, 2012, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2012/06/20126186461265506.html; “Yemen’s Army Retakes Base Seized by Qaeda Militants,” Reuters, September 30, 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/09/30/us-yemen-violence- idUSBRE98T0BS20130930

40.Hakim Almasmari, “Militants Attack Hospital at Yemen’s Defense Ministry, Killing 52,” CNN, December 16, 2013, https://www.cnn.com/2013/12/05/world/meast/yemen-violence/

41.Al-Dawsari, Breaking the Cycle of Failed Negotiations in Yemen.

42.Mohammed Mukhashaf, “Al Qaeda Deploy in Yemen’s Aden, British Hostage Freed,” Reuters, August 23, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/al-qaeda-deploy-in-yemens-aden-british-hostage- freed-idUSKCN0QS07820150823

43.AQAP appeared to learn from its first ruling experience in Abyan.In 2012, AQAP leader Nasir al- Wuhayshi wrote to the emir of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), “You have to take a gradual approach with [the local population] when it comes to their religious practices…you have to be kind… try to avoid enforcing Islamic punishments as much as possible, unless you are forced to do so.” See Bill

Roggio, “Wuhayshi Imparted Lessons of AQAP Operations in Yemen to AQIM,” Long War Journal (blog), Foundation for Defense of Democracies, August 12, 2013, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2013/08/ wuhayshi_imparts_les.php; see also Rukmini Callimachi, “Yemen Terror Boss Left Blueprint for Waging Jihad,” Associated Press, August 10, 2013, http://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/yemen-terror-boss-left-blueprint-for- waging-jihad

44.Saeed Al-Batati, “Al-Qaeda in Yemen Launches a ‘Hearts and Minds’ Campaign,” Middle East Eye, December 27, 2015, http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/al-qaeda-yemen-launches-hearts-and-minds- campaign-386564271