France’s New Deal and Back Sounds in the Arab World

By December 8th, marches were rallied across different French cities but mainly Paris to represent a peak of three-week protesting of President Macron’s decision to raise fuel prices, following more than 900,000 signatures of a popular petition against the recent act. An estimated number of 300,000 protestors wearing highly-visible yellow vests have blocked the roads in 2,000 points across France, while polls showing 66 to 80 percent of French people support the uprising. Violence, looting, and burning have shaded the largely peaceful marches, but support continued to rise. A storming collective outcry reflected first a deep grieve over the country’s declining living standards and erosion of buying power. By mid-December, the movement started to gain radical thrust with calls for an entire new deal. Violence from both protestor and police sides led to custody of 2,000 civilians, thousands stabbed and injured in street fights, and one dead. The Banque de France announced that expected growth in the fourth quarter of 2018 will halve from 0.4 per cent to only 0.2 per cent with more losses on sight if the government fails to survive the anger. The French finance minister’s expectation was even worse; on Monday 10th December he announced the expected annual growth as only 1.7 per cent.At first, the protests did not reflect any discernible effect on Macron. After volume and severity have peaked on Saturday December 8th, as a u-turn of the intended tax policy was widely considered ‘insufficient’, demands included wealth redistribution, salary rises, reforms of the pensions policy, increase of minimum wage and more social security payments to alleviate the harm on France’s middle class and poor citizens. A public speech on the following Monday vowed to accelerate ‘overtime’ measures, reform of unemployment insurance, civil service and pensions system, and increase of minimum salaries. However, Macron’s reverential rhetoric was second to, and has not reversed, two land sliding decisions in 2017: to reduce corporate tax from 33 to 25 per cent and to overhaul the watertight protection of labor to allow companies hire and fire employees through direct negotiations and limit unions’ ability to affect the process. The latter slapped a decades-long protocol that signed France’s business world and affected most French citizens’ employment security.

While some protestors have approved the latest concessions, far-right opposition leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Marine Le Pen, president of the national Rally considered the new policies ineffective to a ‘considerable part’ of the French people and that the government have failed to recognize the social and cultural dimensions of the Protests. Yet, a poll by ‘OpinionWay’ on December 11th showed that almost half of the French population were convinced by the president’s promises while 51 per cent said they were not convinced. Titled a ‘president of the rich’, Macron is widely perceived as a disconnected, arrogant, and ‘know-it-all’ elitist who serves the upper socio-economic classes and whose policies emerge as natural continuation of earlier performance under François Hollande presidency. The fuel crisis has further crystalized this image; Pauline Bock quotes a Yellow Vest protestor reporting to Le Monde “The elites are talking about the end of the world while we’re talking about the end of the month”.

Despite all, Macron has survived a no-confidence vote on December 13th and protests were expected to slash back after the new measures. According to analysts, weather and internal disputes over the movement’s representation and future were sufficient for self-destruction. However, root causes and circumstances driving its force are probably unchanging. Although the average income per capita is 31,137 USD a annum, the country has been struggling with a considerable income gap by which 20 per cent of the richest citizens earn almost five times the income of the bottom 20 per cent. Along with only 1.8 median growth, 9 to 11 per cent unemployment rate since 2013, and raise of taxes or decrease of benefit for pensioners, a €3.2 billion tax cut on the wealth of 350,000 high earners with assets exceeding 1.3 million euros, all has ballooned anger at the current government choices and raised calls for an entire ‘new deal’.

A new social contract …

A new contract between citizens and state authorities is envisioned by many scholars and analysts on ground of serious challenges beyond the national socio-economic determinants in France. Neoliberalism has driven successive governments to entitle middle class and poor citizens of developing the entire ‘model’ of progress.

Because theory and practice envision competition as ‘the’ defining aspect of human relations, citizens in neoliberal classics are defined as consumers whose market choices reward the merits and punish inefficiency in better ways than any state planning- Monbiot writes. The theory pays little attention to the fact that merits are produced and passed down through unearned advantages- inheritance, class, wealth, education- while ‘inefficiency’ indicates redistribution gaps that trickle down to the majority of citizens. Knowingly, however, in his article, Monbiot asserts neoliberal economies have recognized efforts of a more equal society as “counterproductive and morally corrosive”. While blaming unemployment on individuals rather than dwindling market opportunities and households’ debts on ‘feckless and improvident’ earners instead of unequivocally increased housing expenses, bad planning of metropole cities and weathering purchase power, the situation has worsened by growing inflation and failed financial policies since 2007.

The ‘Economist’, a staunch supporter of neoliberal politics for 175 years, has recently published an issue on the successes and failures of neo-liberalism, attesting that the recent twenty years have turned societies into few winners and a majority of losers, created business aristocracies/monopolies, and shut people out of prosperous cities. The Journal’s ‘Manifesto’ confesses that liberal elites have become comfortable with power and lack the interest in reform. The article takes evidence from recent poll results showing only 36% of Germans and 9% of French to have hopes of a better-off upcoming generation and only third of American believed that democracy is vital. Meanwhile, between 1997-2017, the share of military rule supporters has risen from 7 to 18 per cent in the United States[1].

In line with these results, Monbiot asserts that a ‘market’ set as a natural truth as gravity laws camouflages ‘investment’ as milking of existing assets for rent, interest, dividends, and capital gains by indicating meanwhile the creation of wealth through socially productive and useful activities, which rarely occurs. As technological advances lessened dependence on human effort and international trade brought more competitors to the global market, many jobs were relocated outside Europe and the surviving workers were pressured to ‘renounce union protection and social benefits to remain in work’[2]. Instead of unions, people began to rely on self-efforts to realize economic stability and richness amid enormous market anxieties, giving rise to American entrepreneurial businesses, e.g., ‘Amway’, that capitalized on distributors’ thrive for self-employment to promote false promises of quick richness during the 1970s. Contriving a Multi-level Marketing (MLM), business owners profited billions from the distributors’ time and effort in return of $20-30 average take-home income while avoiding all financial entitlements towards regular workers – healthcare service, unemployment support, pensions, etc[3].

Privatization of social services, promoted for efficiency, led American universities between 1993-2013 to accept more students from the top 1% of wealthy households than from the bottom 50 percent[4]. In Britain, Garner reported wealthy students are reported as 10 times more likely to get admitted into top universities than students from poorer homes. This has affected economic mobility of average middleclass workers and driven a lagging income growth. For example, the wealthy 1% households in the US own 40 percent of privately held wealth, today’s average hourly income has only about the exact purchasing power it had in 1978, and the bottom 90 percent of Americans hold 73.2% of all debt. In Europe, income equality performed better than in the USA, but still top 20 per cent of population receive 5.2 times as much income as the bottom 20 per cent, which raises demands of a ‘well-functioning system of social transfers and social assistance and wealth rather than labor based taxation’. Coupled with a slow retreat from welfare policies since the 1970s, harsher unemployment conditions, lower pensions for retirees, more paid for health care, and increased atypical occupational statuses with restricted access to security and support mechanisms of full-time careered salaried occupations, the European middle class has been struggling with a decades-crisis in disposable incomes. Endless policy fixes by liberal technocrats barely spoke to these problems. Thereof, disappointment at Macron’s rich-oriented policies resemble in much part that in the US during Obama’s presidency as top 1 per cent of population got two thirds of the income growth while poverty among poor black children remained astronomical. Obama’s indecisiveness in confronting Wall Street criminals laid ground to the rise of far-right extremists who populated Trump’s electoral campaign in 2016. Likewise, the election of Macron capitalized heavily on the education level of his electoral base, as the less-educated had voted widely to Marie Le Pen, his populist far-right competitor, and people with degrees chose Macron. A deliberate distinction between the have and have-nots and higher preference of Macron in areas with less share of working-class electorate explains partly why the majority of Yellow Vest protestors were young unskilled and/or unemployed laborers. That middle-class employees have joined poor unskilled laborers in their uprising indicates a growing disappointment at recent changes in the country’s labor code and the consequent threats to job security of millions of professionals and white-collars. Macron’s retreat to welfare policies and raise of minimum wages may well down-mute the populist anger among his electoral base, but the spillover effect in Arab countries is yet to show, as neoliberalism and austerity measures have coupled decades of iron-fisted rule by para military and military elites whose political and social legitimacy have always been remained. But even in homeland, experts draw causal relationship between weak popular support to neoliberalism and authoritarian governments’ application of austerity measures in Europe and the United States.

The financial crisis and rise of authoritarian liberalism

In the past, the correlation between ‘free market economics’ or economic liberalization and authoritarianism, even dictatorship, was evident in Asian and Latin America countries. The case is new to European politics and the United States, although neoliberalism’s checkered history with dictatorship is traceable to Hayek’s distrust of social justice and commentaries on political authoritarianism[5].Challenges to the authority and legitimacy of domestic European regimes have been on rise throughout the decade following the 2007 financial crisis. Decline of the social democratic party in Germany in 2009 elections to a record low since 1945; loss of support for the Swedish Social Democratic Party (SAP) in 2010 nation-wide elections after continued political hegemony since 1920[6]; defeat of the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) in 2011, all were signs of weaker support to classic political agents after the decline of neoliberalism’s aura and the retreat of European social democratic policies[7].

The crisis root back to conflictual historical and conceptual dynamic between capitalism and democracy. Critiques of pairing democracy with progressive political-economic prosperity under neoliberalism are referable to years before 2007[8] given that both Rawls and Habermas have disregarded the importance of economic and ideological power as means to political domination. The democratic culture was taken for granted despite the capital market’s individuation effect that weaken collective bargaining platforms and enable greater inequality. In Wilkinson words: ‘Business monopolies, marketisation, competition and profit motives can and do lead to the erosion of solidarity’ and communal ties that democracy needs”[9]. This theoretical dynamism did not translate to political authoritarianism immediately. In 1970-4, neoliberalism was marketed politically in Britain by ‘pitching’ people against labor ‘unions’ to mobilize discontent against the social democratic government which failed to manage the 1973 recession following the rise in oil prices. Under Thatcherism, blue and white collars’ expectation of what is achievable even under a progressive government had retreated and a general consent that ‘no other alternative’ was almost achieved. After 2007 crisis, this effort to mobilize popular support or neutralize resistance and dissent through concessions and midway compromises has withered away. Direct application of austerity policies and marginalization or exclusion of affected groups were followed through “the constitutionally legally engineered self-disempowerment of nominally democratic institutions, governments, and parliaments’. Measures were imposed by the Euro-regime and ‘Troika’ institutions (IMF, ECB…etc) included painful ‘privatization, liberalization, labor market reforms, and regressive tax increases’[10]. A coercive abandoning of institutions that used to genuinely moderate the wrenching nature of socio-economic restructuring in post Thatcherism economies has triggered a growing use of disciplinary techniques regarding worker unions and interest groups[11], replace workfare instead of welfare, and bypass of constitutional norms, mainly representative democracy and legality, to maintain currency and price stability, fiscal discipline, and market competitiveness[12]. This marked a retreat from consensual ‘third-way’ neoliberalism towards more coercive policies, and the state’s relative autonomy from society and normalization of inequality, commodification of social relations. The legitimacy of these policies’ constitutive rationale, constituted and applied by the Maastricht treaty, have eventually been shaken.

Consequently, politics were reduced to one political economic rationale and governments have hindered possible contestation of resource allocation and spontaneous ‘just’ redistribution. Some statistics elaborate striking facts about the French economy and crisis-management policies. The 2007 crisis did not dent the financial revenues or fortunes of the ‘super rich’ whose income increased by nearly 7 percent for the top 10 per cent between 2004-2010 while 19.6 per cent of the most vulnerable groups- single-parent families, retired women and young people under 18 years- were struggling to stave off poverty in the same period 2009-2010. In 2013-2014, non-performing-loans (NPL) of households have peaked to USD 1,624.933 bn following an all-time high of overall of 4.5% in December 2013. While this resonates to an overall increase in Europe households’ NPL that reached 4.6 in 2017, urging the European Systemic Risk Board to issue a report on resolving the continent’s financial crisis, the peak in France was driven by extreme austerity measures to meet the government’s target of cutting state deficit to three percent of GDP in the same period- i.e., 2013-2014- by performing tax increases and spending cuts which together diminished average households’ purchase capacity by -1.5 points annually between 2007-2014. As dispensable household income shrinks while earners resort to unpayable overdrafts, punitive laws gained wider application; by 2015, a report by the Council of Europe concluded a 23.3 per cent increase in the number of prisoners per 100,000 of the total French population and a 31 per cent rise in prison population to reach 76,111 prisoners. The figure indicates how taxation, and redistribution policies reflect ‘disciplinary’ neoliberalism by which “law is applied instrumentally as tool of the powerful capital monopolies”[13] whose fortune increase while more households struggle with debt, imprisonment, and appropriation risks over growing NPL across the continent.

Many analysts explain the overwhelming Yellow Vests uprising by ‘capitalism that went from good to bad’; in fact, it reflects refuse and even defiance of institutional discourse that insulated neoliberals’ policies from social and political dissent[14]. Meanwhile, academic backing from within the liberal thought is heavily recalled. Consistent negligence in orthodox writings of the effect of capital and ideology towards political domination give rise to critical theories emphasizing democracy’s preference of business monopolies’ interests even in times of crisis[15]. The Irish example is instructive. In numbers, the IMF’s bailout of Ireland with a €67.5bn rescue loan protected bondholders and investors within the EU who refused to accept that their investment in sovereign debt are only 80% of their original value, instead of helping individual Irish people through the financial crisis[16]. Bond holders insisted to remain immune to losses and load the whole suffering on property owners who lost their assets’ value, even though the crisis is obviously a macro failure of the banking system. At once, individual property owners became homeless and stripped of social safety. Housing rent increase left young workers to miss out on the recovery; more than 8 percent of the Irish live in consistent poverty; and a recent Irish Times/Ipsos MRBI poll report that the government enjoys support of only 37 percent of voters who are satisfied with her policies[17]. In short, the bailout served only one third of the nation- the rich.

No wonder, then, that 2007 financial crisis has given way to political populism which beckons and gains more grounds in France, Italy, and many other central and Eastern European countries- e.g., Front Nationale and Alternative fur Deutschland[18] in response to growing socio-economic inequality, dislocation, and blocked upward mobility of poor and middle-class electorates. This is how Europe turned to non-democratic liberalism.

Back sounds in the Arab world

Yellow Vest uprisings have garnered a growing support in the Arab world. In Egypt, where irony, sarcasm, and spoofing are bread and butter of millions. Facebook users have created and shared tens of memes relating the French uprising to the enormous wave of protests in 2011 and recalling unforgettable experiences, media commentaries, and official announcements. Comparisons were driven by several similarities including the spontaneous and leaderless outburst of anger, the use of highly-visible symbols and intrusive protesting techniques, and the socio-economic motives represented in poverty, austerity policies, and social inequality. The following screenshots reflect few examples of some widely-circulated memes.

Comment: France needs a genius figure like Azmy Mugahed to uncover the truth about the situation in France.

Referring to a featured video: Azmy Mogahed: “France needs a president like Sisi to get out of the crisis”.

Comment: “France has chosen potato” in reference to Sisi’s angry comment in the World Youth Forum on complaints about the rise of potato’s price to 13 EGP “ Do you want to build your country or search for potato?” which, in turn, raised a wave of sarcasm ‘fried or boiled?”

Attached is a featured new: “French PM confirms fuel tax suspensions, calls for calm”

Comment: “French people: take care of your country!”

Referring to Sisi’s announcement: “I will die in a couple of days and my advice to the Egyptians: take care of your country”.

Comment: “Tell them- “Will you build France or eat potato? and shout. Did you drive bicycle in public?”

Referring to Sisi’s interview with Egyptian program presenter Lamis Al Hadidy where he shouts: “Will you eat the country at end?!”

Comment: “I swear with whatever you believe in- I lived 10 years with only cheese croissant in my fridge”

Referring to Sisi’s talk in the Youth Conference 2016 saying: “I lived 10 years with only water in my fridge” raising a flow of irony on twitter “Sisi’s fridge”

Comment: “thanks Allah we did not do this in 2011 or else they would have drowned us”

Comment: A voice from future says: ‘Nooo, do not take photos with tanks’

Referring to the popular hailing of army troops when it stepped down to secure the protestors in Tahrir Square against Riot Police attacks, before a bloody take-over of power lead to killing of over 1,000 peaceful protestors in Rabi’a Square, then protesting a military coup by Gen. Sisi in July 3rd 2013.

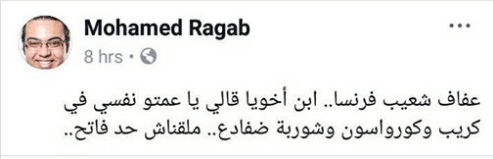

Comment: Afaf Shoaib of France – “my cousin says: ‘oh aunt! I am starving for a crepe, croissant, and frog soup. All shops are closed’. Shoaib decries: He is only a child!”. Referring to Afaf Shoaib’s comment condemning the Egyptian protests 2011 because her cousin could not eat pizza or beef ribs.

The widely circulated memes triggered some outlandish media and political responses. Mohammad Ramadan, a lawyer who wore a yellow vest in Ironic support for the French protests, was incarcerated on grounds of inciting anti-government protests and promoting false news. The former chief of the Dubai Police forces, Dhahi Khalfan, posted a since-deleted tweet accusing the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood movement of inciting the protests against the Macron government. Mohamed Al Baz, a distinguished writer in Youm7, one of Egypt’s most circulated newspapers, contrived that the MB are active leaders of protests in France because authorities have been tracking of the organization’s funding sources. More comedy came with a silent outlawing of use of sell of yellow reflective vests in Egypt. According to Hamza Hendawy, authorities restricted the sell of yellow vests to walk-in buyers, restricted wholesale sales to a few number of trusted companies and only with a police permission. To put off possible critiques, Sisi said in a comment to ‘Happens now in Egypt’ TV Program that the Egyptian media must highlight the cheapness of fuel in Egypt when reporting on the fuel protests around Europe.

The official response in Egypt drives attention to remarkable similarities between the motives of 2011 protests in Egypt and those of the French uprising, especially after worries of social unrest driven by austerity measures. In November 2016, Egyptian authorities took a critical decision to float the national pound in effort to meet the IMF demands in return of 12 billion loan package. In few days, the exchange rate of USD to EGP has risen from 9 to 13, making way to 18 EGP for each dollar by end of 2018. When people protested against Mubarak, currency devaluation moved from 5.8 to 7 by end of the one-year rule of Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president, and then to 18 throughout five years under President Abdul-Fatah Al Sisi.

The socio-economic repercussion of these decision has been reported differently in international and national portals. Statista, a worldwide statistics portal, reports the overall unemployment rate has increased from 8.8 per cent in 2007 to around 12 percent in 2017, while unemployment among youth has loomed between 34 and 35 per cent between 2012 and 2017. CAPMAS, the government’s official portal for statistics, reports that 27.9 of household breadwinners suffer from unemployment. Likewise, Statista reports that Inflation amounts to 20.86 percent in 2018 compared to 10.2 percent in 2016, but national figures and studies indicate that inflation in annual price index has ranged over 31.7 percent since 2017 while increase in food commodities alone reached 41.7 percent[19]. Thereof, the minimum cost of food for a four-member family in 2017 has risen to EGP 2,835 ($157.5). When compared to an average weekly income in public and private sector of 1050 EGP, which is around USD 233 or 7.8 per day, minimum wage of EGP1200 (USD70) and a minimum pension is EGP 750 ($42)- according to CAPMAS reports, both international and national figures of poverty levels become questionable. The UNICEF and World Bank report poverty to have reached 27.8 per cent while CAPMAS says it is 30.2 per cent nationwide and 60 per cent in upper Egypt where households cannot afford basic food, shelter, and health needs, especially in Assiout and Sohag governorates. Both figures fall behind the truth. The poverty line in Egypt is measured at around 750 EGP monthly, which is 40 USD/month or 1.33 USD/day, while the international poverty line is 1.9 USD/day. Therefore, many national analysts estimate extreme poverty in Egypt to have well reached 50 per cent nation-wide and much more in upper Egypt compared to 2015 figures. Still, poverty and income statistics fail to convince official media portals that Egypt is NOT a cheap country for the majority of its own populace, even if it counted eighth among the cheapest 50 counties in the world.

To abate possible unrest, the private sector has already increased salaries by 20-25 percent in 2017 while the government has increased basic public salaries by 14 percent for registered and 20 percent for unregistered employees for year 2017-2018. Some pension deals were raised by 15 percent but, overall, the increase do not coop with soaring inflation rates that pressure middle and low income groups who spend more than 40 percent of income on food, and 60 percent on health and education- as an EIPR study concludes[20]. The reform burden is further explicable in another study that reports the increase in base electricity tariffs between 2016 and 2018 as 28.7 per cent in average for all price brackets. The increase was not negligible for low and middle-income households whose bills hiked by 22.1 and 25.2 per cent respectively. This corresponds well to general inequality identifiers. Although promoted as necessary to reform the economy and minimize the government deficit, the reform toll was unequally distributed between upper and lower segments and safety nets for the affected majority were insufficient or even absent. Before the reforms, the World Bank’s Gini Index[21] of Egypt in 2015 was 31.82. A year later, it reported top 10 percent of Egyptians to enjoy 48.5 of gross national income compared to only 18.2 per cent to the bottom 50 per cent of population. Still, the Gini coefficient places Egypt well regarding income inequality, but local figures after one year of reforms provide a different scene. In 2016, the CAPMAS considered an Egyptian family that spends LE 60,700 annually (nearly LE 5,000 per month) as among te richest 10 percent of Egyptians, while the poorest spend LE 3,300 annually (LE 277 each month). Moreover, EIPR reports that the richest person in a city account for 100 times more spending that the poorest[22]. Globally, Egypt is listed the eighth worst country in wealth distribution. wealth distribution figures give a more realistic view of the situation. The richest 10 percent of Egyptians holds 61 percent of total wealth, despite earning only 28.3 percent of income. The share hiked to over 73.3 percent in 2014 according to a Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report[23]

But Egyptians might have a stronger cause to ally with the French protestors against Macron government. At the lest the French have the demonstration luxury. They can mobilize and organize marches safely without risking their lives behind bars or through extra-judicial killing. Egyptians, on the other side, do have a fight with Macron who has been a staunch supporter of the oppressive military regime that deposed a democratically elected president – Mohamed Morsi. In his meeting with President Sisi 24/10/2017, Macron asserted support to the austerity measures in Egypt through the ‘French Development Agency’ and that he ‘will not lecture Egypt on human rights”, referring to instability and religious extremism that Egypt fights on its own terms. This comes amid accusations by several human rights organizations, namely Amnesty and FIDH, who condemn the French government and military companies for indulgence towards repression in Egypt. To abate migration flows through Egyptian shores, a treaty to exchange four Gowind 2500 corvettes worth around €1 billion since 2014 was followed by additional two corvettes worth 500 million Euros. signed during Marcon’s visit to Egypt in May 2018 as means to transfer the technology’s ‘know-how’ and to cut short the time needed for building the 6 contracted corvettes. Military cooperation treaties worth at least €6 billion included sell of 24 Rafale combat aircraft, a multi-mission frigate, and two Mistral warships since 2013. While conventional military equipment was partly justified to combat terrorism in northern Saini, many French companies are involved in supplying law enforcement agencies in Egypt with powerful digital tools that allowed security services establishing an ‘Orwellian control’ system to disperse and offset any attempt to demonstrate or mobilize dissent against the government’s overwhelming anti-poor and anti-human rights policies. In a report published 02/07/2018, FIDH stated that “some companies have sold to the security services technologies for individual surveillance (AMESYS/NEXA/AM Systems); mass interception (SUNERIS/ERCOM); personal data collection (IDEMIA); and crowd control (Safran drones, an AIRBUS/THALES satellite, and Arquus (formerly RTD) light armored vehicles adapted to the urban environment). In so doing, they have all participated in the construction of a widespread surveillance and crowd control architecture aimed at preventing all dissent and social movement and leading to the arrest of tens of thousands of opponents and activists.” Even conventional weapons such as “Mistral warships (DCNS); Fremm frigates (DCNS); gunboats (Gowind); Rafale fighter planes; armored vehicles (Arquus); Mica air-to-air missiles and SCALP cruise missiles (MBDA); and ASM air-to-surface missiles (SAGEM)” were responsible for killing, torture, and detention of thousands of peaceful civilians under the ‘fight against terrorism”. FIDH reports that French military and intelligence exports to Egypt amounted from 39.6 million to 1.3 billion EUR between 2010-2016. More recently, an Amnesty report published 2018 asserted that since 2011 France has been a leading supplier of arms used in military and civil suppression purposes alike and that much attention was given to the multi-billion deals for fighter jets and warships while French companies supply routine security equipment like Sherpa and MIDS light armored vehicles that appeared several times in repression operations of civilians since 2013[24].

While these organizations condemn France for abandoning freedom and humanity principles in favor of economic and security interests, the authoritarian face of neoliberal economies is a stronger force uniting people in Egypt along with the Yellow Vest protestors in France, Belgium, and worldwide. A primary reason for support of dictatorial militarism in Egypt is as much economic as ideological- rejection of political Islam when brought to power through democratic elections. The long-term toll of neoliberal policies is increased socio-economic and political instability that affects Europeans as well as people in the Middle East. The socio-economic repercussion of multi-national companies’ relocation to cheaper Asian countries or shrink of purchasing power is as destructive, if not less, as imprisoning of 60,000 breadwinners, and forceful disappearance and extra-judicial killing/shooting of thousands of innocents whose families struggle with austerity policies, lack of welfare services, and income instability- all beside the social wrenching and tormented livelihood accompanying life under a criminal regime. If not for liberal principles that ignited intellectuals thought throughout centuries, neoliberal policies must be balanced through sound democratic solutions that accord the ‘right-to-choice’ to all individuals and all nations, which also means suspension of sell and use of weapons against peaceful civilians under claims of ‘war against terrorism’. Egyptians have every cause to join the French against Macron’s neoliberal policies. They have equal right to live safely and prosper in their homeland instead of throwing their lives to the sea only to get caught by high-tech French corvettes and face detention threats afterwards. A social democratic solution in France should bring discourse to neoliberal market givens but also seek to subside the socio-economic unrest in countries where support to dictatorship is cause to horrific national and international crises.

[1] The Economist, “The Economist at 175: A Manifesto for renewing liberalism” 13/09/2018, via: link

[2] Colin, Nicolas, “The Yellow vests don’t need cheaper gas, they need a new deal for the entrepreneurial age” Forbes, 17/12/2018 via: link

[3] Mondom, Davor “The conservative business model that paved the way for the Trump presidency” Washington Post, 11/10/2018, via: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2018/10/11/conservative-business-model-that-paved-way-trump-presidency/?utm_term=.be3af6ed8c03

[4] The Economist, ibid.

[5] Cf. W. Scheuerman, ‘The Unholy Alliance of Carl Schmitt and Friedrich Hayek’ (1997) 4 Constellations Cited in Wilkinson, A. Michael “Law, Society, Economy Working Papers” Forthcoming in E.Mamopoulos and F. Vergis (eds.) The Crisis Behind the Crisis: the European Crisis as a Multi-Dimensional Systemic Failure of the EU, Cambridge University Press, 2018, p.9.

[6] J. Rawls, Political Liberalism (Columbia University Press, 1993); J. Habermas, Between Facts and Norms:

Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy (MIT Press, 1995). In Wilkinson, 2018, p.8.

[7] Bruff, Ial, “The rise of authoritarian neoliberalism” Rethinking Marxism published online 28/10/2013 on: link p.114

[8] See S. Hix and A. Follesdal, ‘Why there is a democratic deficit in the EU: a response to Majone and Moravscik’ 2006, 44 JMCS 533-62 in Wilkinson, 2018, p. 5.

[9] Wilkinson, 2018, p.8.

[10] Wilkinson, ibid, p.5

[11] See Brown Willy, Bryson, Alex, and Forth, John, (2008) ‘Competition and the Retreat from Collective Bargaining’ NIESR Discussion paper no.318, August 2008. Retrieved on 17 December 2018 via: link

[12] Wilkinson, ibid, p.3.

[13] In Bruff p.116.

[14] Ibid, p.115.

[15] see writings of the Frankfurt School of Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer.

[16] In Inman, Phillip, 22.11.2010 ‘Ireland Bailout: Who Really Benefits?’ The Guardian. Retrieved from: link

[17] In Inman, Phillip, 16.06.2018 ‘Ten Year on, how countries that crashed are faring’ , The Guardian, retrieved from: link

[18] On Europe and Nationalism see the BBC map: link

[19] See the recent CAPMAS issue on price indexes published December 2018 on: link

[20] The Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR).

[21] Gini measures inequality between 0 (everyone has the same income) and 100 (richest person has all the income. See: link

[22] Both reports are cited in link

[23] Cited by Osama Diab “Egypt’s Widening Wealth Gap”, published May 23, 2016 and accessed via link

[24] Also see Amnesty, “Egypt: France flouts international law by continuing to export arms used in deadly crackdowns” 16/10/2018. Accessed 07/01/2019 on: link and Amnesty, “Bloody Repression in Egypt: Stop the Sale of French Arms!” 16/10/2018. Accessed 07/01/2019 on: link