Militarization of Political Parties in Egypt

Militarization of Political Parties in Egypt

Militarization of Political Parties in Egypt and Consolidation of Tyranny: A reading in the transformations of party life in Egypt after the coup of July 3 2013.

Introduction

The political system in any country is usually linked with the party system and how it is formed, in addition to the electoral system in force. Therefore, if we want to understand the current Egyptian regime and its orientations accurately, we should understand the form of party system that has been established since the military coup of 3 July 2018, including both new and old components, and the way of its establishment. We should also take into account its political environment, whose main features were: a formal constitution that is deliberately overlooked and violated by the regime, false elections that had nothing to do with reality, and a regime that used to practice violations and repression systematically.

During the past years, the Sisi regime has tightened control over the political life, the media, and the sovereign bodies (This term usually refers to intelligence and security services in Egypt) through two parallel paths of: subjugation and violent exclusion. This can be clearly seen from the cases of subjugation inflicted on most of the Egyptian media, and the violent exclusion of most of the political forces that actively participated in the January Revolution. The process of tightening control over these tracks resulted in concentrating power in the hands of Sisi, perhaps more than what used to be during the eras of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar Sadat, and Hosni Mubarak. With the end of the 2018 presidential election and his new term in power for the next four years, Sisi seems to be working to create a political system that depends on a more subjugated partisan life, including only a few parties that should play the roles of the ruling party and the opposition, but all under Sisi’s control.

This paper seeks to understand the process of restructuring political parties within the parliament, and the objectives that Sisi seeks to achieve through such process, as well as the significance of its timing: after Sisi’s “victory” in the last “presidential election”.

First: Party Map in Egypt after January 2011

The January Revolution represented a rare opportunity for the Egyptian parties to remove the obstacles and inhibitions of political action as well as the accumulated oppression during the Mubarak era, with the possibility of starting a political life that could encourage work, party competition and even participation in government, which had been impossible for political parties under Mubarak. On the other hand, the areas of freedom created in the wake of the January Revolution motivated and justified the establishment of new parties that hoped to experience the political work and participate in the Egyptian government. Therefore, political parties emerged for the first time since 1952 as a major tool for political expression and representation of different sectors of the population. This was clearly demonstrated by the leftist, liberal, Islamic, nationalist and rightist parties, which were quickly formed and started direct communication with the masses without any restrictions.

It is noteworthy here that Egypt did not know any law for organizing the work of political parties after the end of the monarchy until 1977, when Sadat signed the first political parties law (Law 40/1977). This was followed by several amendments to the law, especially the amendment made by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) in March 2011, removing any restrictions that used to hinder party work in the past, and gave the opportunity for real partisan life that unfortunately did not last long.

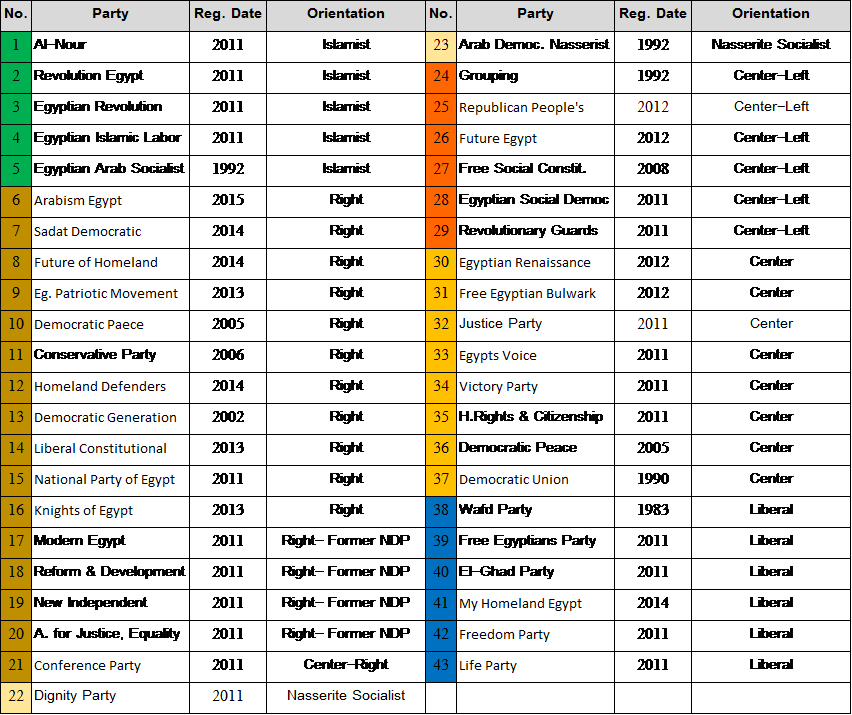

The map of the parties that participated in the 2011 parliamentary elections included new parties that were established after the January Revolution (2011) and the old parties that were founded under the Mubarak era, where the percentage of new parties that participated in elections reached 80% of a total of 41 parties, while the percentage of the old parties that participated in elections was only 20%. These rates of participation, amid clear differences in the attitudes of the participating parties, point to a period of time marked by real partisan pluralism that Egypt had not seen for decades.

The following table shows the list of parties that participated in the 2011 elections:

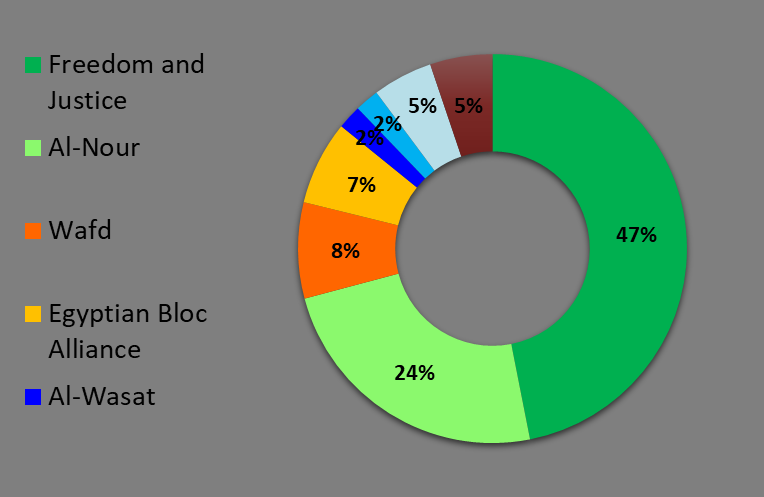

The results of the 2011 elections and the size of popular participation reflected the Egyptian people’s awareness of the freedom and integrity of elections as well as people’s recognition of the real partisan pluralism that emerged after January 2011. The popular participation in elections reached nearly 60% of the total number of voters, which is the highest percentage in the history of parliamentary elections in Egypt. In light of the high level of competition between the different parties, the election results reflected the different orientations of the Egyptian people and the diversity of their components with different relative weights, which was difficult to measure or precisely identify during Mubarak’s reign (Figure 1).

(Figure 1): The results of parliamentary elections in Egypt 2011:

Second: The party map in Egypt after July 2013

Although the atmosphere (of freedom, cooperation and unity) experienced by Egyptians in Tahrir Square during the January Revolution marked the beginning of a new partisan life and the freedom of political practice, the party life in Egypt soon returned to the previous polarization patterns that were hidden under the constraints and repression during the Mubarak era. However, the degree of polarization was much more than ever before. The military soon took advantage of this opportunity to re-formulate political life in the wake of a military coup that they led in the summer of 2013. After the coup, a new phase – never known over Egypt’s modern history – started. The new era under Sisi has been characterized by the erosion of political life and the elimination of all its manifestations, the exclusion of active parties and civil society organizations, and prosecutions and arrests of activists through a mad repression machine that ultimately led to terminating the political life and creating a new reality, over the span of two stages, as we will explain later:

First: The post-coup phase

The Egyptian regime’s attempts during that stage to make the first government (headed by Hazem al-Beblawi) that was formed after the July 3 coup d’etat seem like representing a number of different parties (actually those that supported the military coup) did not succeed and did not continue more than seven months. [A few number of Beblawi’s government belonged to the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, Al Wafd Party, Al-Dostour (Constitution) Party, and Al-Karama (Dignity) Party.] Soon Beblawi’s government was dissolved and the a new government headed by Ibrahim Mahleb was appointed. The new government was devoid of any party representation and was also very similar to the NDP governments during the era of Mubarak.

The regime worked during this phase to impose a new political reality through dealing with political parties through interlocking paths: through banning, infiltration, or subjugation, especially the parties that were active after the January Revolution. The regime also established or supported a number of new parties through its “sovereign organs” later. The role of the organs of sovereignty was prominent in the establishment of these new parties, most notably the “Future of Homeland Party”, which was reportedly established by the Military Intelligence, and the “In Love of Egypt” election list which reportedly was formed by the General Intelligence Service, for participation in the 2015 parliamentary elections.

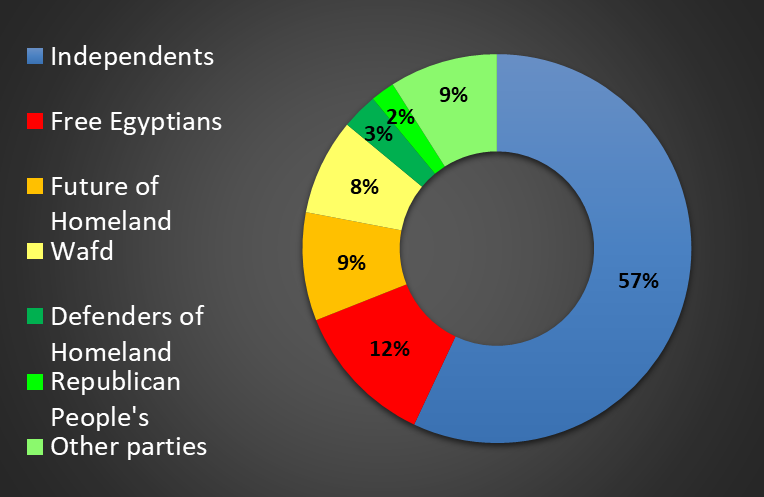

These policies adopted by Sisi and his regime in dealing with political parties resulted in undermining any form of political practice and real party life in Egypt. The parliament of 2015, where most of its members were chosen by the sovereign bodies, reflects this reality clearly. The number of winning parties in the parliamentary elections reached 19 parties, led by the Free Egyptians Party with 65 members and the Future of Homeland Party with 57 members, while the number of members Independents reached 325 out of the 568 elected members of parliament (Figure 2).

It is important to refer here to the size of the popular turnout in the 2015 elections, which according to the statistics released by the Egyptian regime, reached 28% – although it is far from reality in light of a simple comparison between the scenes of the turnout in 2011, where the electoral commissions were extremely crowded and those of 2015, where electoral commissions were almost empty. Also, it is difficult to rely on the exaggerated reports narrated by the regime. The difference between the rate of turnout in both elections reflects the Egyptian people’s awareness of the reality of political and partisan life that preceded elections in 2011 and 2015.

(Figure 2)

In light of excluding the influential and effective parties in the Egyptian street and in light of the new parties’ lack of programs, political projects, or even a specific ideology to distinguish them from other parties, such parties, whether they were basically established or supported by the regime, failed to win a number of seats approaching two-thirds of the seats in parliament. However, it seems that the regime sought to make for the absence of a party majority in the parliament by the formation of a coalition, including a number of parties and a number of independent members. Therefore, the “Support Egypt” coalition, which was composed of 317 members, emerged to perform certain roles similar to those played by the ruling party in any other parliament. (The number of “Support Egypt” coalition was approaching the limit of two-thirds of parliament members.)

It is important to indicate the extent of changes in the partisan life after the coup of July 3, 2013. Here we can point to the absence of about 50% of the parties that participated in the 2011 parliamentary elections, from the 2015 parliamentary elections: as 41 political parties participated in the 2011 elections while 21 of them refrained from participating in the 2015 parliamentary elections. This percentage clearly reflects the size of the practices and violations that Sisi and his regime used at that stage against the political parties that were effective and influential after the January Revolution. Thus such parties refrained from participation in an electoral process that its results appeared from the first glance that they were pre-cooked by the regime.

The following table shows the map of the parties that participated in the “parliamentary elections” of 2015, and shows the absence of a large number of parties that participated in the parliamentary elections of 2011:

This stage was characterized by randomness through the size of overlap and competition between the sovereign bodies on managing the new political scene. Despite the apparent control of the regime over the political parties within the parliament of 2015, the direct involvement of the sovereign bodies and the competition between them to manage the political scene have confused the regime in more than one situation in which the new emerging parties, as well as the individuals who have been pushed into political life, seemed to be confused in dealing with the regime’s political decisions. This can be seen through tracking the conflicting statements of members of parliament while addressing the resolutions and laws approved by the regime during that period, most notably the state of confusion regarding Sisi’s waiver of Tiran and Sanafir through an agreement with Saudi Arabia, and the Civil Service bill.

To sum up, the outcome of this stage was the regime’s monopoly of the political life through its sovereign bodies that maintained entanglements and interventions that did not allow even the emergence of a formal partisan life in the parliament.

Second: The post-2018 election phase

It seems that the randomness that characterized the movement of political parties in the first phase of the Sisi rule would not continue during his second term, both externally and internally. On the foreign level: Amid the ongoing criticism directed against Sisi for undermining and weakening political life, it seems appropriate to create a new political life characterized by strong party pluralism through the presence of a limited number of parties under the parliament, playing both the roles of the ruling party and the opposition. At the internal level: It would be appropriate to control the randomness of political parties, especially with the start of a new presidential term that is likely to witness constitutional amendments and further adoption of laws and decisions.

Sisi’s repeated statements in more than one occasion calling the political parties for integration, followed by statements in the same direction by the Egyptian parliament speaker and some members of parliament, clearly indicate that the restructuring of political parties in the parliament will be a priority for Sisi during his second term, through several parallel paths, including:

1- Mantaining control over political parties within the parliament

It was clear that Sisi was unwilling to allow any of the parties that were active after the January Revolution to play any effective role which could hinder the regime’s domination over the 2015 parliament similarly to the scene of the 2011 parliament that was out of the regime’s control. The Free Egyptians Party was a clear example for this: Although the party won 65 seats in the 2015 parliament, about 12% of the total number of parliament seats, and was on top of the list of the largest parties in parliament, soon internal crises grew and deepened within the party, resulting in the end in the removal of the party founder and financier, Naguib Sawiris, and the entry of the party indirectly under the umbrella of the regime. Later, about 50 parliament members belonging to the party resigned and joined the Future of Homeland Party, one of the most prominent political arms of the sovereign bodies. Thus, the Free Egyptians Party lost its leading position as the largest party within the parliament.

The Wafd Party has also started to go in the same direction, after suffering several internal crises over the past few years. Furthermore, the Wafd Party appointed the former military spokesman, Brigadier General Mohammed Samir, who is very close to Sisi, to the post of “Assistant Chairman of the Party for Youth Affairs”.

2- Unification of the grip of control

Intersection and overlapping between the sovereign bodies on managing the political parties file over the last period, prompted the regime to start a new stage by allowing one sovereign body, the military intelligence, to manage the party file, thus reducing the size of overlapping and concentrating power in the hands of Sisi through his preferred sovereign body. This will help the regime to unify its control over political parties through the military intelligence, especially after Sisi’s dismissal of a large number of agents of the General Intelligence Service (GIS) as well as the dismissal of Khaled Fawzi, the GIS director, and the appointment of Sisi’s former office director on top of GIS.

3- Reduction of the number of parties

The number of political parties officially registered and approved by the Party Committee is now 104, with only 19 of them represented in the parliament. However, the regime seeks to reduce the number of parties within and outside the parliament through merging some of them, as well as the resignation of some party members to join other parties. The regime targets reaching a form close to that of the ruling party with one or several other pro-regime parties playing the role of opposition.

What is going on in the Future of Homeland Party clearly reflects the regime’s methodology in restructuring (through disassembling and assembling) the parties within the parliament. The Future of Homeland Party includes as new members those who resign from the Free Egyptians Party and the Wafd Party as well as other independent members. The Future of Homeland Party also announced merging the campaign of “We are all with you for the sake of Egypt” with the party to raise the party members within the parliament to about two thirds of MPs and becoming the majority party. On the other hand, the Wafd Party seeks to lead the pro-regime opposition in parliament by calling on other parties to merge with them and enter under the party’s umbrella.

However, the regime will face a legal and constitutional obstacle to complete the process of including the resigning members in other parties, as Article 6 of the Law on the House of Representatives and Article 10 of the 2014 Constitution require the removal of the MP’s membership if he/she changed the electoral capacity on the basis of which he/she was elected. Whatever the legal procedures that the regime will take, it will pass the process of changing the partisan status of members of parliament without causing the removal of the MP’s membership, whether through a constitutional amendment, or through activating the articles of the Constitution, which requires the approval of two thirds of the members of parliament to remove membership of one of the parliament deputies. This means that removal of MP membership is impossible in light of passing the regime’s new policies regarding the merging of political parties by members of parliament. The final product of this stage will be to reach a political scene similar to the political scene under Mubarak’s rule: through a ruling party that is directly affiliated to the head of state and a group of pro-regime opposition parties that are expected to be under Sisi’s control more that the opposition during the Mubarak era in the absence of any popular grassroots for them.

Third: Sisi & Mubarak: Comparison between two eras

Mubarak’s favorite method in dealing with the opposition parties has been to subjugate them by giving them enough space for breathing and engaging in political action. This has contributed to giving some legitimacy to the Mubarak regime. However, opposition parties during Mubarak’s era remained under the ceiling set by the regime and no more: All opposition parties were not allowed to exceed the limit of one third of parliament members. Anyway, the so-called “cartoon” parties (referring to the weakness of these parties) survived under the Mubarak era, albeit ostensibly, through relying largely on their history in participation in partisan life as well as the history of some of their prominent figures.

However, Al-Sisi was appalled by Mubarak’s way of dealing with political parties, which would no longer be appropriate in an environment that still has revolutionary features, and that any space for political action could represent a threat to the regime and weaken its grip. Therefore, Sisi adopted a new and different political reality through the exclusion of influential political parties and at the same time the involvement of new political parties, prepared in the corridors of his sovereign bodies, to carry out the policies dictated by the regime.

Mubarak and Sisi are both involved in undermining and weakening political life but in different ways. While Mubarak used the least expensive way by subjugating the existing political parties at the time by providing a limited space for breathing and performing political action with a low ceiling under his control, however, Sisi has used an expensive method that would have far-reaching consequences. He sought to undermine the existing partisan and political life and created new pro-regime political entities and parties that will not require exerting any effort for subjugation. Thus, Sisi believes that such policy will provide him with the necessary legitimacy as well as the formal democracy that he could employ to cover up his incessant abuses and tyrannical practices.

As he is on the threshold of new four years in power, it seems that the timing for Sisi is now appropriate for reorganizing the tools and strategies of governance and the formation of institutions and organizational structures that will contribute to controlling the process of monopolizing political life and putting it in a seemingly organized framework, achieving several objectives, including:

1- Seeking a popular support

Sisi understands that he cannot rely solely on sovereign agencies and the media machine to mobilize the masses, build popularity and promote his decisions. This was clearly demonstrated during the “presidential election” in 2018: despite harnessing the media machine to mobilize citizens, as well as the pressures practiced by the sovereign bodies on individuals and institutions to drive them to the ballot boxes. However, the poor turnout seemed very clear and the gap seemed more extensive than ever before between the regime and popular grassroots in all governorates which prompted Sisi to think about building popular grassroots through a big NDP-style party, representing the popular support in cities and villages, and one of his tools in mobilizing people in any upcoming elections.

2- Ratification of laws continuing

It is sufficient to point out here that members of parliament ratified within 10 days (starting from the first session that was held on 10 January 2016 until the thirteenth session that was held on 20 January 2016) some 341 legislative decisions out of the 342 that were issued during the era of Adli Mansour and Sisi, in the absence of the parliament. (Only one decision, related to the civil service law, was rejected). The size of laws that were ratified and the short time during which these laws were discussed (or rather not discussed) shows clearly the key role played by parliamentarians, which is expected to continue with the new form of parties and coalitions after their restructuring, but through a mechanism that will avoid the confusion, randomness, and the conflicting statements of MPs witnessed by the parliament during Sisi’s first term.

One of the most important decisions that is expected to be passed by the parliament in the coming period is related to the extension of the presidential term or the addition of new presidential terms through undertaking constitutional amendments to allow Sisi to stay in power.

3- Democratic decor is necessary

Despite the severity of the regime’s violations and practices against all those who try to practice political activity outside the regime’s circle of control and direction, however, the regime remains keen to export the scene of a stable political life and the presence of partisan pluralism, albeit formal, that represents a democratic decor to legitimizes the regime internally and externally. The regime does not care about the fact and reality of such partisan pluralism, as those parties within the parliament will hardly have any role in forming governments, formulating policies, or seriously practising control and supervision over authorities.

Conclusion

The desire to control the political arena and to maintain the army control over governance has remained one of the main features of the Egyptian regimes after 1952 (except for the period of Dr. Mohamed Morsi). It seems that this attitude did not change so much during the era of Sisi. Abdul Fattah Al-Sisi sought to create a new political environment that did not exist during the years of Mubarak’s rule or the period that followed the January revolution, leading to the restructuring of these parties. Although the political environment is fragile, yet no much effort is required to control it. This new political environment will provide the desired decor and the required democratic form as Sisi seeks to reduce the foreign pressures and criticism practiced against him regarding the situation of the current political life and the ongoing human rights violations. At the internal level, it is appropriate to promote a state of illusion in which all things seem to be fine, and of course presenting Sisi as the indispensable leader to manage this stage.

In the short term, Sisi will benefit from a political scene that seems more organized than that which was during his first term in office; but in the medium and long terms it will be impossible to develop a healthy partisan life in the context of such authoritarian rule. The process of restructuring political parties, along with Sisi’s practices of undermining the parties that were out of his control, will not only affect the partisan life and political practice in Egypt, but they will also reflect on the Egyptian society, amid absence of any popular role under the extremely difficult economic and living conditions.