Role of State in Social Accountability

Role of State in Social Accountability Implementation: Lessons from developing countries

Abstract

As most of the literature focuses on the role of civil society to advocate for social accountability practices as a bottom- up model; however, it ignores the central role of the state for designing policies and plans to support these practices. It is; therefore, important to assess critically this concept in order identify best practices that governments can follow. This paper advocates the central role of the state (top- down) for effective social accountability implementation to improve public service delivery. Furthermore, paper examines a model of state involvement that offers good practice for developing countries to follow through examples such as Bangladesh, Pure, Philippine and Uganda. It concludes by highlighting the fact that to improve public services delivery through SA, there are many factors have to be occurred such as, adaptation to the local context, cooperative relationship among all the society stakeholders. However, the most significant factor is political willingness.

Key Words:

Good governance, State, Civil society, Social accountability, Service delivery, Political leadership.

It is important to note that, despite the successful social accountability initiatives in those particular countries, they might not fit local contexts in other developing countries without adjustments. Thus, it is important to question if the policy is transferable or not. In regard to this, Campbell’s (2009) findings provide convincing evidence to suggest that considering the bricolage in policy transfer process is the most important issue. He emphasizes that when the organizations change, they may require a reorganization of institutional ideologies and functions in novel and original ways, or to apply new components into previously existing institutional practices. Similarly, to draw lessons from other countries, Reinholde (2006) focuses on policy implementation and proposes a range of features that are likely to be correlated with the transferring process.

Introduction

Concurrently, a number of recent studies has focused on social accountability initiatives to assist positive service delivery outcomes; however, there is a lack of data concerning the assumption of the citizen participation without considering the state as a central actor in these initiatives leads to attain no change (Clark, 2007; Imposes, 2010; and Ringold and Holla, 2012). Such studies have tended to emphasise the role of civil society to enhance citizen participation rather than thoroughly analyse achievable mechanisms to enhance the citizen-state relations as well as the crucial role of the state for designing policies and plans to create an appropriate environment for these practices (ODI, 2007). However, there is an absence of rational consideration to state impact on social accountability process, especially in the context of developing countries. It is worth noting that state here refers to the political elite or leadership will that is responsible for failure or success of SA initiatives, not the civil society advocacy tools in authoritarian regimes. For instance, so far, much of the democratic literature has tended to focus on social accountability as a bottom-up form of accountability; therefore, civil society is considered the main actor in the awareness, advocacy and implementation process. In contrast, Kamath and Vijayabaskar (2009) claimed that there is not enough evidence of successful so-called “top-down” social accountability implementation and that, therefore, civil society is the sole player in SA implementation. Advocates of this approach do not adequately address the problem of complex contextual relation between the state and citizens in authoritarian regime; however, Blair (2007) emphasized that the presence of a vigorous and dynamic civil society does not prevent the presence of a strong state.

The paper investigates thoughtfully the significant role of state (Top- Down) to support the social accountability implementation for improving public service delivery through employing the case study method. In other words, to ensure improving public service quality through social accountability approaches, the role of the state cannot be ignored. Thus, it critiques the above argument and reveals the significant role of the state especially in authoritarian regime for successful SA implementation. It is important to note that this paper is not attempting to provide a broad investigation and assessment of social accountability initiatives in the mentioned case studies. Instead, the aim is to present evidence of the crucial role that the state could play in SA implementation with the objective of improving public services.

Ackerman (2005) emphasized that social accountability is one of the rising approaches to achieve a democratic society. On the other side, accountability is confronted here as a practice within a principal-agent affiliation. In this affiliation the manner and performance of the agent is assessed contrary to prearranged criteria by the principal and faults are sanctioned (Baez-Camargo, 2011). To address this issue, Joshi (2008) stated that the social accountability — or as some literature named it, “demand for governance” — is another form for bottom-up accountability. Clark (2007) defined the term of Social accountability ( 1) as a set of principles with a range of tools and activities – that includes the perspectives of those who are traditionally and structurally disadvantaged and with rigorous analysis of information and evidence seeks to hold public sector actors responsible for the performance of their functions. These comprise among others, citizen-budget, access to information, parliament hearing, and service delivery (Jayal, 2008).

The World Bank (2004) highlighted that social accountability aims to provide citizens the chance to express their choices on particular concerns to contribute in an expressive manner to policymaking, or to hold public officials accountable for explicit choices or performances. In this respect, the question raised here is what crucial role should the state play to create an enabled environment for social accountability practices? To answer the research questions this paper aims to examine the situation of a specific community in a specific country. The case study will be the best fit method. To demonstrate the entire picture, it is very important to highlight various social service programmes that have been implemented in developing countries and have succeeded in supporting social accountability. This includes, for example, the “Report Card” in Social Programs in Peru; the Government-Watch and Social accountability in the Philippines; and the water service delivery monitoring program in Uganda.

The paper is structured as follows. It starts with a vibrant and direct relation between practice of social accountability and good governance. The paper likewise draws on current literature that has attempted to address this paper’s focus (Citizenship DRC 2011; Tembo 2012). Then paper emphasizes the importance of context or appropriate environment element for successful social accountability implementation to improve public service delivery. Lastly, it highlights some of the applied assessment of case studies that emphasized the crucial role that can be played by the state to support social accountability initiatives to improve public service delivery, as well as explore what kind of state- citizen relation exists in authoritarian regimes. Moreover, it focuses on various approaches that captivate local public bureaucrats to improve the responsiveness mechanisms in different contexts.

The Significance of Social Accountability in Governance Sphere

More recent evidence suggests that the concept of social accountability is considered one of the main governance approaches to donors and policymakers as one of the more capable approaches to build bottom-up democratic governance processes. Since it provides level specifically at the border where the state and citizens interrelate, whether or not institutional capacity for this exists (Ahmad, 2008). The concept of SA has a broad definition; however, to identify the validity of SA approaches this paper adopts one definition to draw explicitly the impact of SA on enhancing governance. Indeed, social accountability denotes the “set of tools that citizens can use to influence the quality of service delivery by holding providers accountable” (Ackerman, 2005a). It is therefore a new approach that aims to emphasize public participation through reshaping the state-citizen relationship within a principal-agent theory.

In this respect, Speer (2012) maintains that current empirical investigations are mainly focused on the relationship between cooperative action by citizens and their influence on policy change and enhanced service delivery. It can thus be argued that SA is a practice of participatory democracy that aims to facilitate people and state interaction in a more democratic direction. Consequently, it is generally acknowledged that the theory of participatory democracy (2 ) , for example, is one of the main approaches to SA analysis.

Pateman (2012) identifies it as “a process of collective decision making that combines elements from both direct and representative democracy as citizens have the power to decide on policy proposals and politicians assume the role of policy implementation.

” He states that direct citizen participation is, in fact, what differentiates social accountability from other traditional instruments of accountability.

There is considerable evidence to show that social accountability initiatives are gradually likely to endorse good governance outcomes. For instance; Malena at.el (2004) holds that there are four core principles underlying the importance of SA. These are: growing the responsiveness of local government, revealing government failure and corruption, empowering disadvantaged groups, and assuring that national and local governments react to the concerns of the poor. Such objectives are implemented through an array of SA mechanisms and methods such as community score cards, citizen report cards, participatory assessment of local service delivery, citizen based ex-post auditing and participatory monitoring of attaining and execution of local government contracts (Joshi, 2008). Thus, these objectives could be achieved through improved public service delivery and more well-informed policy plans.

Likewise, Anjum, Anushay and Chase (2008) emphasised that the notion of social accountability is attractive as it is presumed that cooperative action may (a) enlighten better choices and develop policy strategies, (b) effective implementation due to social participation, and (c) better monitoring and faster sensitivity to complaints. Regarding this point, Menocal and Sharma (2008) argue that SA approaches allow citizens to achieve improved public services, as the active citizen’s voice leads to a change in public officials’ motivations; public officials adapt their behavior in response to stresses and, as a result, quality of, or access to, public services improve.

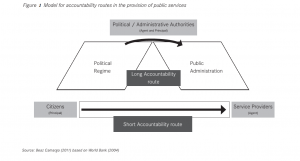

In this respect, the World Bank (2004) promoted citizen participation and transparency through a “short route” in public service delivery–direct accountability relationships between users and service providers. On the other hand, the “long route” includes citizens holding the government accountable through political representation instruments, and then the government (through official instruments in the public administration) holding providers accountable for providing public services to the citizens. Therefore, a long route is indirect and requires reasonable institutional performance. To demonstrate the argument it is appropriate to refer back to the World Bank’s 2004 model, where long and short accountability routes are recognized (see figure 1). It can thus be argued that SA has a key value in showing that government is open to citizens and that they are involved. This can add to better political trust and legitimacy, and contribute to minimizing conflicts, as well as provide policies more linked to citizens’ needs (Abakerli, 2007).

Social Accountability and Contextual Implementation

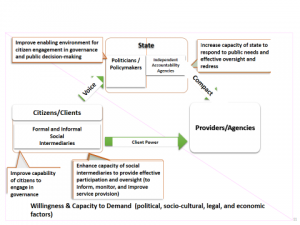

Another issue concerns a broad recognition of how socio-political context which is crucial in profiling, building, and breaking social accountability implementation in developing countries which most of them have been ruled by authoritarian governments (see figure 2). Jayal (2008) points out that the context will affect which SA goals are achievable or appropriate in the local context, and which approaches or initiatives are applicable to implement them. As a result, what appears to be more important are the concrete practises of politics and power of those regimes towards the governance issues. This ties in with an extensive respect in the international development community that “context matters” (Grindle 2007; Levy 2011).

In a similar vein, Baraka (2008) provided convincing evidence that recognizing the impact of the context of public services such as economic, political, and social elements, will drive policy makers to rethink the interrelations between different stakeholders involved in the reform process. Thus, despite the many authoritarian regimes in developing countries are rhetorically committed to achieve social accountability; however, there were no clear policies that turn the rhetorical commitment to be a real commitment. For instance, the examples of developing countries have been chosen for this paper’s purpose to illustrate clearly the crucial role a state can play to address what needs to be done and what can be done to create an enabled environment of SA practices. In this respect, O’Meally’s (2013) findings provide convincing evidence that highlight when a SA practice has no accessible channel through which to influence the incentives of service providers—for example, to accelerate the cost of depraved performance it is questionable that concrete results can be achieved through participatory instruments of SA.

Yimenu at.el (2011) suggest that to react to, and adopt, SA initiatives to fit a specific context, several factors need to be in place, such as a willingness from the political leadership and state bureaucrats to support this policy, and to create a facilitating environment for civil society organization. Furthermore, more concerns about accountability have been introduced into the New Public Management (3 ) (NPM) literature, as a part of the discussion on public sector reform. This discussion emphasizes that the creation of an encouraging environment to apply SA approaches leads to successful implementation. Further research in this area revealed that it is important to take into consideration that the adaptation process of SA depends on enhancing the capability of public officials through efficient incentives’ system and that directly relies on the political will to support SA implementation (O’Fl ynn, 2007). Indeed, there is an array of cases in which SA has been reasonably successful in its aims, and there are many others where it has been a rational failure, with outcomes that are not beneficial for governance or development (Dervarajan et al. 2011; Gaventa and Barrett 2010). Thus, the success or failure of SA initiatives is formed by both the approach in which SA is implemented and by the context of its implementation.

The Civil Society or State for Successful Social Accountability Implementation

Civil Society:

So far much of the literature has tended to focus on social accountability as a bottom-up form of accountability; therefore, the civil society has been considered to be the main actor in the implementation process. It is important here to define the civil society term as:

“Those not-for-profit organizations and groups or formations of people operating in the space between the family and the government, which are independent, voluntary and established to protect or enhance the interests and values of their members” (Miller, 2002).

Hevia (2011) focused on the role of civil society for effective SA implementation and ignored the role of the state to facilitate this process. He states that the CSO is the most important actor in SA implementation process as it advocates accountability transformation and ensures the involvement of more marginalized people in the decision making process. Hevia argues that, CSO plays a critical role in social programs, which require a context of awareness about citizens’ rights and knowledge regarding public services provided through these programs. Likewise, Salamon and Sokolowski (2004) highlight that civil society has been widely acknowledged as a crucial “third” sector. They argue that CSOs should be strengthened to have a forceful impact on state bodies. In their view, civil society is seen as an increasingly important actor for supporting good governance; therefore, SA implementation.

The proponents of this approach emphasized that CS main responsibility is holding government officials accountable, leveraging government policies and lobbying for reform, and advocating for effective public services (Arroyo and Sirker, 2005). In developed countries, there is no doubt that civil society is very robust to sort out these functions. In developing countries, however, the CS has been controlled and regulated by the political power, which results in a weak CS to organize these functions. Therefore, many international organizations and donors have focused on building the capacity of civil society in developing countries to manage these tasks and ensure SA grass-roots successful implementation and ignored the significant role of the state to support SA.

State:

In contrast, other studies suggest that the significance of political will and a whole political context that provided a well-adjusted approach to SA is an important principle for success (Joshi, 2008). Although the proponents of this approach agree that character and comprehensiveness of CS is essential in shaping the form and success of SA; however, they provide evidence that CS is not able to implement SA initiatives apart from government support which expresses clearly political will. For various reasons CS is rarely a remedy for challenging embedded accountability issues. For instance, CS is bounded by the political context, and can find it problematic to distance itself from this politics (Booth, 2012). Another critical reason relies on the capability of CS to build productive networks and coalitions with pro-reform actors to ensure the success of social accountability in many cases. This however, network and coalitions cannot exist within the state without a legislative framework that allow CS to work efficiently and liberally. This legislative framework is crucial to CS-government collaboration and economic support (Blair, 2000).

Consequently, Reinholde (2006) underlines the state’s capability to impose the rule of law, set strong rules of engagement for civil society and endorse a public policy agenda, creating a favourable environment for SA implementation. Additionally, the nature of the state-citizen “social contract”–refers to the common expectations of the rights, roles, and commitments between the state and citizens, which in a certain context can affect the form and success of SA. It can, therefore, be argued that improving public services in any developing country is based on two aspects. First, matching the role of the government to its capability – the previous mistake was that the government made too many efforts given limited resources and inadequate capacities. Thus, the developing state should cooperate with other stakeholders, such as international donors that provide funding to the SA initiatives. Second, strengthening the capability of the government through revitalizing public administration bodies, to empower them to perform their facilitating, monitoring and synchronizing roles (Haque, 2001). Besley and Ghatak, (2007) thus, stated that a comprehensive study of the impact of accountability initiatives in service delivery exposed that success as dependent on two factors: context (the legal and policy setting and the strength of civil society organizations) and political will (the political support of civil servants).

As cited above, many sources have emphasized the fact that voice without actual tools to successfully hold the state accountable is not enough to attain change. In this respect, Bukenya, et.al. (2012) address that the nature of the state and the actors from political elites that rule and work together with state bodies are as essential as, if not more so, civil society in developing the shape and effectiveness of SA initiatives. In a similar vein, Unsworth and Moore (2010) underline that any democratic reforms are usually political, when political leaders tend to challenge influential interests that take advantage from low levels of government responsiveness or lack delivery of citizens’ rights.

Claasen, Alpín-Lardiés., and Ayer (2010) tend to examine influential interests that benefit from low levels of accountability or poor public service delivery. Thus, they concluded that accountability reforms are mostly political, and not a result of CS advocacy strategies. For instance, if politicians and leaders do not have the real intentions to improve public services delivery, putting additional pressure on official state bodies; thus, SA is barely successful to achieve its ultimate goal. In contrast, when the political leadership has a real commitment to improve public services, CS may have a role to play as a facilitator through employing its mechanisms to create an interactive relationship between public officials and citizens (Devarajan et al. 2011).

The important role that the state plays to support SA initiatives is apparent; therefore, it can be argued that instead of the international focus on building CS’s capacity to ensure SA successful implementation, the focus should be shifted to build the state’s political capacity— means its abilities to keep sufficient political stability for social transformation and maintain collaborative and appropriate relationship with various social actors. In this respect, Unsworth and Moore (2010) emphasized that the degree of the political capacity is a main actor in shaping the accommodated form for SA initiatives in several ways.

Civil Society vs. State:

To identify models of social accountability facilitation, it could be argued that it is necessary to take into account the relationship between civil society and the state that sets fundamental parameters for successful SA implementation. Whilst most consideration of success factors for SA focus on the state or CS, governance academics increasingly debate a more synergy-based approach, which also emphasizes the instruments and actions of collaboration between both. Such approaches identify that state-society factors do not exist separately from one another, but may be mutually dependent, reciprocally productive, and in practice, the barriers between both may become tremendously slurred (Calland and Neuman, 2007). Indeed, it is evident that this relationship can become essential in achieving the best model of state facilitation of SA.

Consequently, Anjum, et al, (2008) emphasize that there can be a range of other factors needed to be identified and classified to adequately explain the relationship between the state and citizens. For instance, the practice and effectiveness of SA is formed by the deepness and nature of networks between state and society members, such as parties, CSOs and labour unions (Fox, 2007). The presence of a vigorous and dynamic civil society does not prevent the presence of a strong state. For instance, Hickey (2011) argues that society already has existing formal and informal accountability practices, making SA implementation seem more effective. Thus, Fox (2004) suggests that to articulate change in the governance implementation process, the transformation process should be supported from all of society’s actors. Although there are implications of this increasing state-civil society transformed relationship, further stages have to be taken to ensure the improvement of the public services delivery in developing countries. In other words, the transformation process depends on changing the balance of power between reform supporters in both state and society, and reform opponents, who are also in both the state and society.

Examples of Successful SA initiatives implementation from Developing Countries

To answer the key questions, this paper employs case study approach to explain the crucial role of state intervention for successful SA initiatives that might offer good practices for other developing countries to follow. These following cases illustrate various experiences that present various geographical regions and share the similarity of the socio-economic nature as well as institutional framework.

1- The “Report Card” ( 4) in Social Programs in Peru

After the collapse of the Fujimori government in September 2000, the Peruvian community was yearning for both more accountability and extended democracy. The corruption scandals that brought down the president left the population with mistrust of government and Fujimori’s control had created patterns of rule that restricted the democratization of the Peruvian state (Felicio and John-Abraham, 2004). It was therefore expected of Paniagua’s transitional government, and Toledo’s government later, that they highlighted accountability and public participation in their effort to rebuild state legitimacy (Felicio and John-Abraham, 2004). In the past years, however, social programs have mostly been employed based on partisan interests and have included limited participatory approaches (Cevallos, 2003).

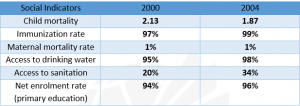

In this respect, Ackerman (2005) has stated that in countries with a large inequality and social marginalization – a third of Peruvians live in poverty and extreme poverty, particularly in the rural regions with low quality of public service – , achieving good quality of service delivery will not be possible only through technical interference or by maximizing resources to local councils. Essential and sustainable adjustments can only be achieved if Peruvian people are more engaged in the agenda-setting and change of social policies, as well as in the procedures, to ensure that their demands have been appropriately considered and addressed (Brinkerhoffet al., 2007). For instance, one of the most significant strategies taken during the transition era was the establishment of the “Round Tables for Attacking Poverty” (RTPR). The aim of this forum is to institutionalize the participation of local communities and civil society in agenda-setting and decision-making, as well as to monitor poverty-related plans (World Bank, 2001). This forum engaged government bureaucrats and representatives of local community and civil society organizations (CSOs) for developing social policies to fight poverty. As a result, the government succeeded to reduce poverty (See table 2).

Furthermore, the Peruvian government has started a process together with local and civil society representatives to implement a poverty alleviation plan. This plan has three core components: justice in access to public services, incorporating mechanisms for discussion and public participation and institutional enhancement by capacity building of government officials at the service delivery (World Bank, 2004). For instance, an interesting project named the Participatory Voices Project (2003 -2011) was conducted in partnership between CARE Peru and CARE UK. The government implemented five social programs, which were selected because they provide state coverage and are connected to the citizen’s basic needs. The pilot projects were chosen to implement the so-called report card approach. These projects were: Glass of Milk, School Meals, Care provided in public health facilities, non-school-based Early Education Program and the Rural Work (Frisancho, 2014).

The aim of these projects is to have a participatory assessment mechanism to measure user satisfaction with the quality of public services. It also aims to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each program, through reliable and direct data gathering from the users of the key Social Programs. This project worked towards strengthening governance in the government and to provide civil society with a participatory assessment mechanism. The “Report Card” mechanism assisted the comparison of social program performance in various regions and over time (Cevallos, 2003). Additionally, many stakeholders were involved in the RTPR, such as the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, local users and the World Bank. This RTPR played a vital role in coordinating local organizations in the selected districts, which gathered data through focus groups and surveys. The Presidency of the Council of Ministers functioned as a coordinator amongst other public bodies implementing social programs, thus sharing thoughts and obligations for the efficient implementation of the approach employed (Frisancho, 2014).

Another issue of concern is that the project faced many challenges for implementing the new approach, as both public and private actors had struggled to understand the “Report Card” mechanism. Furthermore, the lack of experience combined with social misunderstandings led to suspicions about its effectiveness and doubt of the participatory nature of it. This a natural confrontation to new approaches and fear of being evaluated in the early phases (World Bank, 2004). Conversely, the pilot project was very successful to develop a new management mechanism to monitor and evaluate the governmental bodies’ performance in service delivery. Despite the governmental efforts in facilitating public participation, there is no precise evaluation research available to measure the success of implementation.

Afterwards, the government initiated a decentralization program, generated regional bodies as a new tier of government and started to allocate a significant amount of funds to these sub-national units. Concurrently, it engaged the regional units in a participatory budget, which led to extensive public debates about the main concerns for public investment (Cevallos, 2003). Hence, the impact of this project was large in terms of improving the officials’ capacity and services provided by social programs for underprivileged people through a “system of social accountability,” which was implemented as a “top-down” initiative in Peru. Surprisingly, the current social accountability initiatives still mostly fail to join the Peruvian legal structure (Frisancho, 2014). Andersson & van Laerhoven (2007); however, argued that the commitment that service officials have to perform well is not dependent on legal enforcement, but on the political leadership to endorse the social accountability and public participation.

2- The Government Watch and Social Accountability in the Philippines

The Philippines experienced the revitalisation and expansion of civil society during the 1980s as they mobilized to bring down the authoritarianism of Philippino President Marcos. Therefore, the Philippines have had a large and extended resistance to corruption (Batalla, 2000). The main challenge for the new government in the Philippines was to deal with the lack of accountability (Batalla, 2000). Laws and regulations such as -The acting of the Local Government Code ( 5) – are available to fight corruption and support accountability in public service. However, the government was fragile and influenced by the political elites. Consequently, corruption became a cultural aspect and public services were turned into private possessions. The weakness of democratic bodies thus caused an environment unable to offer citizens the tools to express their needs of good public service delivery (PIDS and UNICEF, 2009).

Over the last twenty years, however, due to disappointments with levels of accountability of public service providers, there have been broad changes in the demands on the Philippines government to reform basic governance practices (World Bank, 2004). Thus, the current government has a solid commitment to intensifying citizen participation and social accountability. The current president, Aquino, marks a vibrant shift in the main concerns of the Philippines government. Aquino created an initiative named “Institutionalizing People Power in governance,” to terminate corruption and poverty through direct participation of citizens and civil society organizations (CSOs). He used a “hybrid” approach to enhance social accountability and improve public service (Magno, 2013).

For example, the Government-watch (G-Watch) project is one of the participatory mechanisms. G-Watch aims to develop practical engagement among citizens, CSOs and the government to monitor community transactions and improve monitoring apparatuses to develop services and counter corruption. This project was initiated to identify a “Ghost Books” problem–which is the disappearance of school textbooks during the delivery phase in 2002; however, it was not effectively implemented until Aquino’s policy of citizens’ participation to monitor the public services was applied (Aceron and Aguilar, 2012).

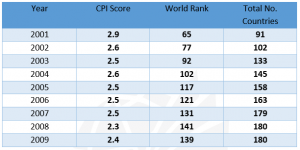

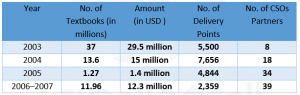

The G-Watch pilot project was implemented in Naga City to enhance and monitor education service delivery for the Department of Education and the local government administration (Douglass, 2007: 3). The Department of Education had faced the challenge that several schools were not able to receive the books they required. The schools complained that just one textbook was available for every six elementary school students, or one for every eight high school students (Wampler, 2013). As a result, the system was deteriorating and students were struggling. Through the support of Aquino’s government at the Philippine Department of Education, G-Watch started a program named “National Textbook Delivery Program” (NTDP) to ensure a comprehensive and appropriate delivery of quality textbooks to schools across the country (Douglass, 2007). G-Watch also worked with local CSOs to monitor delivery locations to ensure that textbooks were accurately delivered (Guerzovich and Rosenzweig, 2013). The NTDP employed a mechanism called “Inspection and Acceptance Receipt” (IAR) to increase the transparency and accountability of the delivery of textbooks, as well as to monitor the quality of the delivered materials (Wampler, 2013). Thus, Arroy (2012) has stated that NTDP was very successful in reducing corruption in the education system during the last years (see table 3 and 4).

Similarly, the Check My School project (CMS) is a community monitoring project that supports transparency and social accountability in the Philippine education department through monitoring the service delivery in public schools. The CMS was initiated by the Affiliated Network for Social Accountability in East Asia and the Pacific (ANSA-EAP) and was under the supervision of the Secretary of Education. The project has used an innovation hybrid method. It combines on-the-ground community monitoring with the easy and affordable use of information and communication technology (ICT). The ICT therefore enabled community monitoring and gave feedback about services provided through an online platform. For instance, users found 231 problems that required solutions in 84 schools (Shkabatur, 2012). Another interesting finding is that CMS is quoted as a “good practice” case in the governance arena, and the governments of various countries are urged to adjust the CMS model in their country contexts (Shkabatur, 2012).

The main outcome of the G-Watch program was a rethink of the role of the state in social accountability initiatives. It contradicts the assumption that sees civil society as the exclusive driver of accountability, as it is the current government creates an enabling environment to implement the community monitoring initiatives and future projects that fits the Philippines’ socio-political context. Thus, the Textbooks Count and CMS projects were employed by engaging state bodies and local CSOs across the country, by using equally sanctions and incentive policies (Wampler, 2013).

Moreover, the participation-oriented conversion actions – such as changing in the civil servants attitude to support public participation-in the Philippines have engendered two key changes. First, the rigorous effort to directly involve citizens has brought larger numbers of citizens into official state-authorized decision-making administrations at the local and national level. Second, the Philippine government has effectively established a range of new institutes that support participation and transparency in service delivery (PIDS and UNICEF, 2009). Some scholars argue that the outcome of this program has not had a direct impact on public services; however, Magno (2013) maintains that the program supported the local environment to improving public services.

3- The Water Service Delivery Monitoring Program in Uganda

Uganda is one of the few countries in Africa to have corruption in the water sector (Velleman, 2010). Although Uganda has vast water resources, the delivery of safe water and hygiene to its people is weak as a result of deprived governance system and corruption. Consequently, in Uganda, several studies has shown that corruption is extensive in the water sector; for example, by using other infrastructure indentures as a bribe (Joshi, 2013). It is important to note that corruption is often accompanied by low quality work that can significantly decrease the quality of water infrastructure in urban and rural regions. For instance, only sixty-five per cent of citizens have access to water infrastructure in rural regions (Bitekerezo and De Berry, 2008).

In 2006, however, as part of the Uganda government’s effort to develop trust within the Water sector, the Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE) created a multi-stakeholder Good Governance Sub-Sector Working Group (GGWG) for recommending concrete mechanisms to monitor transparency and accountability (Joshi, 2013). Despite these actions, the implementation of the action plan was very slow and misrepresented the approved objectives. However, the main reason behind the failure of these actions was the corrupt bureaucrats in the water sector (Bitekerezo and De Berry, 2008).

Thus, the government had to set up an anti-corruption policy to pursue an acceptable service delivery of water supply and sanitation (WSS) services. In 2008, the MWE and the GGWG, in cooperation with the World Bank Institute (WBI), launched a “non-lending technical assistance program.” This program aims to develop governance in water services in Wobulenzi, Uganda through social accountability (Jacobson, Mutono, and Nielsen, 2010). It encompassed pillars for successful implementation, such as an inclusive evaluation of the local context to understand what an enabling environment for supporting governance practices and actual engagement in the water sector looks like. The program improved the capacity building of the local CSOs and assisted in the implementation of applicable social accountability approaches to monitor and assess the performance of Wobulenzi’s water service officials. Moreover, it enhanced the communication to support good governance and collaboration among participants, as well as monitoring and evaluation to analyse the outcomes (Velleman, 2010).

Furthermore, in 2009, the MWE enhanced the program implementation by providing Citizen Report Cards (CRCs) to the water sector to review the users’ satisfaction with the quality and accessibility of water services (Jacobson, Mutono, and Nielsen, 2010). In cooperation with the local CSOs, the MWE conducted (CRCs) a series of sessions to raise awareness of the new policies and enrich community participation in the water sector reforms. Lastly, to assess the process, Uganda’s government conducted water quality experiments from September 2008 to December 2009 to identify any alterations in quality (Sirker and Cotlear, 2010).

In this respect, the water program considerably developed the interactions among Wobulenzi’s water sector, water service suppliers, and the community members. Furthermore, a survey shows that water service delivery in Wobulenzi improved after setting out the social accountability approaches, which led to an increase in piped water and reduced the complications to access water in rural areas. Claasen and Alpín-Lardiés (2010) argue that many households used more piped water than they had earlier, while the number of users facing problems in accessing water reduced significantly. Service providers started to change their performances to improve services in reaction to public feedback. In 2009, follow-up assessment results pointed out that water quality had largely improved. The CRC results also show that users saw increased transparency, accountability and communication (See table 5).

Uganda’s government had a broad intention to improve the quality water service mainly to poor rural settlements. This program, therefore, was very successful to engage users not only as monitors of water services, but as partners in developing policy and improve the services delivery plan. As a result, the water users can currently express complaints to systematic stakeholders and stakeholders are requested to respond to user feedback (Friis-Hansen. Esbern, 2014).

Conclusion:

The understanding of democratic governance as an array of beliefs and values that reinforce state-society interrelations requires intensive investigation of the role of the state to support this governance. Although the paper has provided evidence of successful top-down SA initiatives, much work still needs to be done to shape a cooperative relationship among the stakeholders–CSO, state, and citizens for more effective outcomes. Thus, the discussed cases clearly illustrate that social accountability is a unique approach to improving public service accountability and its success is dependent on the political willingness. In the literature, focus has been on supporting civil society in SA initiatives; however, it has tended to ignore the state’s involvement. The findings of this paper add to a growing body of literature that emphasizes that successful social accountability implementation cannot come about without state involvement. It was argued, as an initial premise, that social accountability can play a key role in improving the quality, reliability, efficiency and justice of public service delivery in developing countries.

The success of the case studies should thus not be considered out of context. Effective social accountability initiatives are dependent on a number of external aspects and, like all things, never happen in a vacuum. Within case studies context, however, the political leadership is the most important factor, as most of CSOs in developing countries lack the capacity and experience needed to implement such initiatives without state support. Moreover, people cannot claim their rights in public services delivery without the government’s effort to create an interactive platform.

Another issue to consider is a need to strengthen the main public service principles, which is important because they would facilitate public sector management. Further research is needed to rethink the role of the state. Scholars and policy makers can initiate a platform to redefine reform opportunities. These should not only consider successful experiences in other developing countries, but also re-examine the latest approaches of administrative development theories. Ultimately, it is important to note that the success and sustainability of social accountability tools are established when they were institutionalized, as well as, when the state has its own internal strategies of accountability. Discussions, conversations, learning by reform disappointments, learning by evaluating policy results, by debating the reasons for slack policy performance, and examining how to deal with the emergent issues can be important phases in this respect.

References

Abakerli .Stefania, 2007. “Strengthening Relationships of Accountability between Government and Citizens: Lessons from a TFESSD-financed Initiative in Ecuador”. World Bank. Washington DC, PP.1-30.

Aceron, Joy, and Aguilar. M, Kristina, 2012. “G-Watch in Local Governance: A Manual on the Application of G-Watch in Monitoring Local Service Delivery”, the Government Watch (G-Watch) Program of the Ateneo School of Government (ASoG) and the European Commission, PP.1-135.

Ackerman, M. John, 2005. “Human Rights and Social Accountability, Social Development papers: participation and civic engagement”, Paper No. 86, World Bank publications, PP.1-190.

(2005a) “Social Accountability in the Public Sector: A Conceptual Discussion”, Social Development Paper 82, March, Washington DC: World Bank.

Ahmad, R. , 2008, Governance, Social Accountability and the Civil Society, JOAAG, Vol. 3. No. 1, PP.1-19.

Andersson, K. P., and van Laerhoven, F. 2007. “From local strongman to facilitator: Institutional incentives for participatory municipal governance in Latin America”, Comparative Political Studies, 40(9), PP.1085–1111.

Anjum, Anushay and Chase S. Robert. 2008. “Demand for Good Governance Stocktaking Report – Initiatives Supporting Demand for Good Governance” (Final Draft). Social Development Department, World Bank. Washington DC, PP.1-156.

Arroyo, Dennis. , and Karen Sirker. 2005. “Stocktaking of Social Accountability Initiatives in Asia and the Pacific”, The World Bank Institute Community Empowerment and Social Inclusion Learning Program, PP.1-89.

Arugay A. Aries. 2012. “Tracking Textbooks for Transparency Improving Accountability in Education in the Philippines”, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), PP.1-70.

Atamneh, Jamal, et.al. 2013. “Baseline Assessment of Social Accountability in the Arab World, Conducted for the Affiliated Network of Social Accountability in the Arab World (ANSA-AW) and CARE Egypt, Integrity Research and Consultancy, PP.1-149.

Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Bank Institute, and UNCDF. 2003. “Local Governance and Service Delivery to the Poor: Bangladesh Case Study”, Paper prepared for the Manila workshop: Local Government Pro-Poor Service Delivery 9th-13th February 2004, PP.1-28.

Aubert, Pascale. 2006. “Actors of Local Governance: Information on Project Approaches and Capacity Building Material and Capacity Building Need Assessment of Union Parishads”, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) Publications, PP.1-201. [Accessed on 24/7/2014].

Brinkerhoff, D. W., Brinkerhoff, J. M., and McNulty, S. 2007. “Decentralization and participatory local governance: A decision space analysis and application to Peru”. In G. S. Cheema, & D. A. Rondinelli (Eds.), Decentralizing governance: Emerging concepts and practices, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, PP. 189–211

Batalla, Erik C. 2000”. “De-institutionalizing Corruption in the Philippines: Identifying Strategic Requirements for Reinventing Institutions”, Paper presented at the conference on Institutionalizing Strategies to Combat Corruption: Lessons from East Asia, August 12–13, Makati, Philippines. http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/APCITY/UNPAN013117.pdf

Bukenya, B., S. Hickey, and S. King. 2012. “Understanding the Role of Context in Shaping Social Accountability Interventions:

Toward an Evidence-Based Approach”, Social Accountability and Demand for Good Governance Team Report, World Bank, Washington,DC.

link [Accessed on 23/6/2014].

Besley, Timothy. , and Ghatak. Maitreesh. 2007. “Reforming Public Service Delivery”, Journal of African Economies, volume 16, AERC supplement 1, PP. 127 –156.

Blair, H. (2000) ‘Participation and Accountability at the Periphery: Democratic Local Governance in Six Countries’, World Development 28(1): 21-39.

Calland, R. and Neuman, L. (2007) ‘Making the Law Work: The Challenges of Implementation.’ In Florini, A (Ed.) The Right to Know: Transparency for an Open World. New York:

Columbia University Press.

Campbell, L. John. 2009. “Institutional Reproduction and Change”, The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Institutional Analysis, edited by Glenn Morgan, John L. Campbell, Colin Crouch, Peer Hull Kristensen, OveK. Pedersen, and Richard Whitley. New York: Oxford University Press, PP.27-43.

Cevallos, Rodríguez. , and Miguel. Antonio. 2003. “From Beneficiaries to Clients: Application of the “Report Card” to Social Programs in Peru”, Instituto CUANTO– Multi-stakeholder Roundtable on Poverty Reduction in: Voice, Eyes and Ears a Social Accountability in Latin America: Case Studies on Mechanisms of Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation, Civil Society Team and World Bank, PP.1-143.

Chibba, Michael. 2009. “Governance and Development: The current role of theory”, policy and practice, World Economics, Vol. 10, No.2, PP.1-85.

Claasen, Mario, Alpín-Lardiés. Carmen, and Victoria Ayer. 2010. “Social Accountability in Africa: Practitioners’ Experiences and Lessons”, Affiliated Network for Social Accountability (ANSA-Africa) and IDESA, PP.1-65.

Carlitz, R. (2010) Background Paper on Budget Processes, Review of Impact and Effectiveness of Transparency and Accountability Initiatives. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

Devarajan. S., Ehrhart. H., Tuan Minh Le, and Raballand. G., “Direct Redistribution, Taxation, and Accountability in Oil-Rich Economies: A Proposal”, Working Paper 281, December 2011, Centre for global development.

Douglass, Frederick. 2007. “Generating Genuine Demand with Social Accountability Mechanisms Report”, World Bank Publications, PP.1-230.

Goldfrank, B. 2007. Lessons from Latin America’s experience with participatory budgeting. In A. Shah (Ed.), “Participatory budgeting”. Washington, DC: World Bank, PP. 91–126.

Guerzovich. F and Rosenzweig .S, 2013. “Strategic Dilemmas in Changing Contexts: G-Watch’s Experience in the Philippine Education Sector”, Transparency and Accountability Initiative, London.

Haque, M.S. 2001. “The Diminishing Publicness of Public Service under the Current Mode of Governance”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 6, No. 1(January/February), PP. 65-82

Hevia, J. Felipe. 2011. “Power and Citizenship in the Fight against Poverty: the case of Progresa/Oportunidades in Mexico,” Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS) In Peter Lang, PP. 1-4.

Hickey, S. 2011. “The Politics of Social Protection: What Do We Get from a ‘Social Contract’ Approach?” Canadian Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 32, No. 4, PP.425–438.

Felicio, Mariana & John-Abraham, Indu. 2004. “Peru: Towards a System of Social Accountability,” Washington: The World Bank, Latin America and Caribbean Region, En Breve, No.39, PP.1-178.

Fox, J. 2004. “Empowerment and Institutional Change: Mapping ‘Virtuous Circles’ of State-Society Interaction,” in Power, Rights and Poverty: Concepts and Connections, edited by R. Alsop. Washington DC: World Bank and DFID, PP.21-43.

______, 2007. “Accountability Politics: Power and Voice in Rural Mexico”. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Friis-Hansen. Esbern. 2014. “Social Accountability and Public Service Delivery in Rural Africa”, DIIS Policy Brief, Danish Institute for International Studies, PP.1-23.

Frisancho, Ariel. 2014. Rights at the Centre: Citizen Monitoring to Promote the Right to Health Care and Social Accountability in Peru in: “Putting Public in Public Services: Research, Action and Equity”, in the Global South International Conference – Cape Town, South Africa April 13-16, 2014, PP.1-37.

Iosos, Mori. 2010. “What do people want, need and expect from public services?”, The 2020 Public Services Trust in partnership with RSA Projects Publications, PP. 1-56.

Jacobson, Maria, Mutono. Sam, Nielsen. Erik. 2010. “Promoting Transparency, Integrity and Accountability in the Water and Sanitation Sector in Uganda”, Water Integrity Network and Water and Sanitation Program, PP.1-110.

Jayal, N. G. 2008. “New Directions in Theorising Social Accountability”. IDS Bulletin, 38(6), PP.1-4.

Joshi, Anuradha. 2008. “Producing Social Accountability? The Impact of Service Delivery Reforms”, Institute of Development Studies, Volume 38 Number 6, PP.1-27.

Kamath, L., and Vijayabaskar, M. 2009. “Limits and Possibilities of Middle Class Associations as Urban Collective Actors”, Economic and Political Weekly (Vol – xliv No. 26-27), PP. 368-376.

Magno, Francisco. 2013. “Report Commissioned by the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency”, in: 2012 Philippine Open Government Partnership Country Assessment Report. (2013). Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, link.

Malena, Carmen., Forster. Reiner, and Singh. Janmejay. 2004. “Social Accountability an Introduction to the Concept and Emerging Practice”, Social Development Paper and Participation and Civic Engagement, Paper No. 76, PP. 1-32.

McNulty, Stephanie. 2011. “Voice and vote: Decentralization and participation in Post-Fujimori Peru”. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, PP.1-320.

2012. “An Unlikely Success: Peru’s Top-Down Participatory Budgeting Experience”, Journal of Public Deliberation, Article 4, Volume 8, Issue 2, PP.1-23.

Menocal Rocha, A. and Sharma, B. 2008. “Joint Evaluation of Citizens’ Voice and Accountability: Synthesis Report”. London: DFID.

Miller, Fred D., Jr., 2002, “Natural Law, Civil Society and Government”, in Rosenblum and Post, eds., 2002, pp. 187-215.

Obaid A. Thoraya, 2003. “State of world population 2003 making 1 billion count: investing in adolescents’ health and rights report”, United Nations Population Fund publications.

O’Flynn. Janine, 2007. “From New Public Management to Public Value: Paradigmatic Change and Managerial Implications”, Australian Journal of Public Administration, Volume 66, Issue 3, pages 353–366.

O’Meally, C. Simon. 2013. “Mapping Context for Social Accountability: A resource paper”, The World Bank publications, PP. 1-35.

Pateman. Carole. 2012. “Participatory Democracy Revisited”, Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 10, No. 1, PP.32-64.

PIDS and UNICEF, 2009. “Improving Local Service Delivery for the MDGs in Asia: The Philippines’ Case”, A Joint Project of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) and United Nations Children‘s Fund (UNICEF), PP.1-321.

Reinholde, Iveta. 2006. “Policy Transfer in Public Administration: How it Works in Practice”, Viešoji politika ir Administravimas, Nr. 16, PP.1-26.

Salamon, L.M., Sokolowski, S.W. and Associates, 2004. “Global Civil Society: Dimensions of the Non-profit Sector”, Vol.2, Kumarian Press, Inc, PP.14-28.

Shkabatur, Jennifer. 2012. “Check My School: A Case Study on Citizens’ Monitoring of the Education Sector in the Philippines”, World Bank Publications, PP.1-205.

Siddiqui, K. 2000. “Local Governance in Bangladesh: Leading issues and major challenges”, The University Press Ltd, Dhaka, PP.1-278.

Sirker, Karen. , and Cosic. Sladjana. 2007. “Empowering the Marginalized: Case Studies of Social Accountability Initiatives in Asia”, Public Affairs Foundation Bangalore, India and World Bank Institute. Working paper. World Bank Institute, Washington, DC, PP.1-234.

Speer, Johanna. 2012. “Participatory Governance Reform: A Good Strategy for Increasing Government Responsiveness and Improving Public Services?”, World Development, Vol. 40, No. 12, pp. 2379–2398.

Unsworth, Sue, and Mick Moore. 2010. “An Upside Down View of Governance”. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. Link. [Accessed on 16/8/2014].

Velleman, Yael. 2010. “Social accountability: Tools and mechanisms for improved urban water services”, Water Aid Discussion paper, World Bank Institute, PP.1-159.

Wampler, Brian. 2013; “Innovations in South Korea, Brazil, and the Philippines”, Report written for the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency, PP.1-128.

World Bank Group, 2001. World Development Report 2000/2001 “Attacking Poverty”. New York: Oxford University Press, PP.1-175.

2004. World Development Report 2004 “Making Services Work For Poor People”, World Bank publications, PP.1-286.

Yimenu, B. Eshetu and et.al, 2011. “Social Accountability Mechanisms in Enhancing Good Governance”, Prepared for the Informal Interactive Civil Society Hearing of the General Assembly in Preparation for the Fourth United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries, PP.1-16.

Figures:

Figure 2:

Source: Jeff Thindwa, World Bank Institute, UNDP Regional Governance Week. Cairo, November 2012

Tables:

Table 1. Selected Social Indicators in Ullapara Upazila—Sirajganj local governance Development Fund Project

Source: Upazila Project Coordinator’s Office, Ullapara. Data need to be validated and sources identified before used for evidence.

Table 2. Peru: Poverty Reduction in Peru by Area (% of population)

Source: Ministry of Economics and Finance (2012). Marco Macroeconómico Multianual 2013- 2015.

Table 3. Transparency International CPI Scores, the Philippines 2001–2009

Source: World Bank Social Accountability Notes 2010. ( 6) .

Table 4. Outcomes of the NTDP, 2003–2007

Source: G-Watch Reports, 2004–2007.

Table 5. Improvements in Water Service, by Provider

Source: World Bank Social Accountability Notes 2010. ( ).

—————————-

References

(1 ) See more: Ringold and others referred to social accountability as a “set of tools that citizens can use to influence the quality of service delivery by holding providers accountable” (2012:7).

(2 ) See also: Aragone`s. Enriqueta, Sa ´nchez-Page´s. Santiago, (2009), A theory of participatory democracy based on the real case of Porto Alegre, European Economic Review 5356–72. (Avritzer, 2002, Baiocchi, 2005, Barber, 1984, Fung Wright, 2003, Goldfrank, 2007, Labonne Chase, 2009, Santos, 2005, Wampler, 2007).

( 3) The main argument is that the “NPM embraces that market oriented management of the public sector will lead to better cost-efficiency for states, without facing damaging side-effects on other aims and concerns”. See also: (Hood, 1991, Barzelay, 2001, and O’Flynn, 2007, Wilson, 2004).

( 4) ) The Report Card develops a mixed (qualitative and quantitative) method for assessment, such as interviews with general and local executives of the Social Programs, focus groups with program consumers, and surveys of a statistical sample of Social Program users. The Report Card has three phases: The first phase records personal information about the services’ users, the second phase evaluates the level of user satisfaction with the social program, and the third phase is deployed to gather further data (Malena, Forster and Singh, 2004).

(5 ) The Local Government Code declared that it is the policy of the state “to ensure the accountability of local government units through the institution of effective mechanisms of recall, initiative and referendum.”

(6 ) The views expressed in this article are entirely those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of EIPSS